On the Rock of Gibraltar you can discover very interesting structures in the limestone in some places, so-called shatter cones. These become particularly exciting when you look at their formation, which is related to meteorite impacts. The listing coordinates mark the beginning of the trail and station 2 the end. You will encounter the shatter cones several times on this relatively short stretch of trail, via the Douglas Path - Ohara's Road - St. Michaels Road.

The Rock of Gibraltar

The formation of the Rock of Gibraltar dates back to the Jurassic period (175-200 million years ago). However, some parts of the Rock of Gibraltar show actions in the recent past, about 5 million years ago. The most recent activity took place when the African continental plate collided with the Eurasian plate. The Rock of Gibraltar is described as a monolithic promontory. The peaks of the Rock of Gibraltar, some of which are over 400 metres above sea level, were formed by early Jurassic dolomites and limestone. It is a highly eroded offshoot of an overturned fold. The sediments that make up the rock are stratigraphically inverted, so the oldest rock layers are on top. The layers are recognisably discarded and deformed.

The formation of shatter cones

A shatter cone is an often conically shaped fracture surface in the rock. On the surface, these cone-shaped fractures have typical fracture markings with a ray-like structure that emanates from a tip (apex). The stripe-like structures can overlap each other, but never overlap. Completely round, i.e. fully developed cone-shaped structures are extremely rare, because rock inhomogeneities may be present. Shatter cones are often bounded by fractures and fissures in the rock, so they begin or end there. The cones may be convex (outward) or concave (inward) to the rock surface.

Besides meteorite fragments, shatter cones are the only macroscopic (visible to the naked eye) traces of an impact. They are formed by the impact of meteorite bodies on solid rock, which has been structurally deformed by the shock waves. The exact origin is not fully understood. It is accepted that they are formed when the shock wave passes through a weak point (e.g. mussel shell, inhomogeneity) in the rock. When a large meteorite strikes the Earth's crust, the rock layers in the area of the impact crater and in its immediate vicinity are exposed to extreme pressure and temperature conditions. Within fractions of a second after the impact, a hemispherical pressure wave with several times the speed of sound spreads out in the rock from the impact body. The surrounding rock and the impact body itself are compressed to about a quarter of their original volume. Depending on the distance from the impact centre, specific changes occur in the rock, such as vaporisation, melting, mineral transformation, mechanical deformation and fracturing.

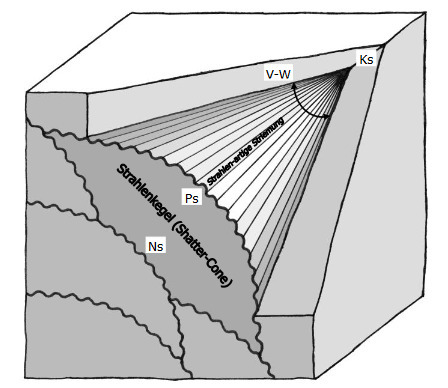

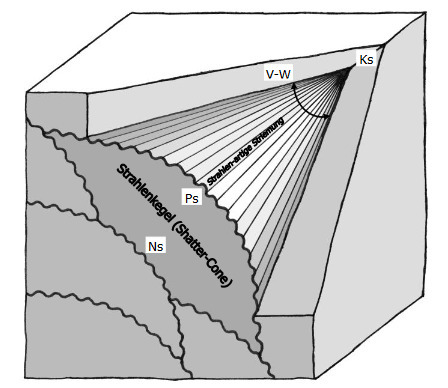

The following images show ray cones as graphics and in the field.

Ks=taper tip/Apex, Ps= positive side (convex surface), Ns= negative side (concave surface)

Abb. Oberschwaben-portal.de

Shatter cones can occur in almost all rock types, but are most pronounced in homogeneous, fine-grained rocks with their peaks and ray-like fractures. In coarse-grained rocks such as granites and gneisses, the ray cones are usually coarse and not very distinct. The size of the cones is in the centimetre to metre range in the impact zone.

Normally, the cone apex points in the direction of the shock source, if the primary position in the terrain remains unchanged, but irregular orientation and even opposite orientation can also occur. If the orientation varies, it is secondary bedded ray limestones, i.e. rock material that was still redeposited during the formation of the shatter-cones. With the help of primary ray cones it is possible to localise the impact site, which is enormously helpful if the crater is no longer present or recognisable today.

In nature, shatter cones are formed exclusively during impact events (impacts of rock, iron and rock-iron meteorites on the Earth's surface) by shock waves and under extremely high pressure between 15 and 200 kilobars. In addition, the formation of shatter cones could be generated experimentally in the laboratory. They have also been observed in artificially created explosion craters from nuclear weapons tests. Shatter cones have never been found in craters of volcanic origin or in rocks of volcanic origin.

A possible theory

Ray cones or shatter cones are products of shock wave metamorphism and today represent peculiar guide rocks or structures for the reliable identification of impact craters. The presence of the ray cones in the Rock of Gibraltar shows that there must have been impact events in the vicinity in Earth's history.

Just as the exact origin of the shatter cones has not yet been fully clarified, there are also various theories on the formation of the Strait of Gibraltar. One theory that would fit the shatter cones present here is that the strait was caused by two meteorite impacts. One impact is thought to have occurred in the western Mediterranean, the second 800 kilometres northwest off the north coast of Spain. This seismic wave reached as far as the Mediterranean Sea. This event took place 5.33 million years ago. Some ripples are also said to still be recognisable on the seabed of the region around the impacts, which were created by the seismic shock waves.

Take a close look at the structures in the limestone and then please answer the following questions before logging!

1. How many shatter cones did you find along the entire route?

2. Describe the shatter cones you found (diameter, completely round or only partially round)!

3. Is the tip of all shatter cones aligned in the same way or do you think there were secondary rearrangements?

4. Do you find the structures in convex or concave form or are there both forms?

5. Take a photo of yourself with a shatter cone and put it on your log!

Send me an email with your answers! After sending your answers you can log right away. If something is wrong, I will contact you. You don't have to wait for the log to be released! Have fun on this geological journey of discovery!

Auf dem Felsen von Gibraltar kann man an einigen Stellen sehr interessante Strukturen im Kalkstein entdecken, sogenannte Shatter cones, auch Strahlenkegel genannt. Besonders spannend werden diese, wenn man sich mit ihrer Entstehung befasst, die im Zusammenhang mit Meteoriteneinschlägen steht. Die Listingkoordinaten markieren den Weganfang und Station 2 das Wegende. Auf dieser relativ kurzen Wegstrecke, über den Douglas Path - Ohara's Road - St. Michaels Road, werden euch die Shatter cones mehrfach begegnen.

Der Felsen von Gibraltar

Die Entstehung des Rock of Gibraltar geht auf die Jurazeit ( vor 175-200 Millionen Jahren) zurück. Einige Teile des Felsens von Gibraltar zeigen jedoch Aktionen in der jüngsten Vergangenheit, etwa vor 5 Millionen Jahren. Die jüngsten Aktivitäten fanden statt, als die afrikanische Kontinentalplatte mit der eurasischen Platte kollidierte. Der Felsen von Gibraltar wird als eine monolithische Landzunge beschrieben. Die Gipfel des Felsens von Gibraltar, von denen einige über 400 Meter über dem Meeresspiegel liegen, wurden von frühen Juradolomiten und Kalkstein gebildet. Er ist ein stark erodierter Ausläufer einer überkippten Faltung. Die Sedimente, aus denen der Felsen besteht, liegen stratigraphisch verkehrt herum, also die ältesten Gesteinsschichten zuoberst. Die Schichten sind erkennbar verworfen und deformiert.

Die Entstehung der Strahlenkegel

Als Strahlenkegel (auch Druckkegel oder englisch Shatter Cone – „Schmetterkegel“) bezeichnet man eine oft konisch geformte Bruchfläche im Gestein. Auf der Oberfläche haben diese kegelförmigen Brüche typische Bruchmarkierungen mit einer strahlenartigen Struktur-Ausprägung, welche von einer Spitze (Apex) ausgeht. Die streifenartigen Strukturen können sich gegenseitig überlagern, aber nie überschneiden. Äußerst selten sind komplett runde, das heißt voll entwickelte kegelförmige Strukturen, weil Gesteinsinhomogenitäten vorhanden sein können. Shatter cones werden oft von Brüchen und Klüften im Gestein begrenzt, also beginnen oder enden dort. Die Kegel können konvex (nach außen) oder konkav (nach innen) zur Gesteinsoberfläche gewölbt sein.

Shatter cones sind neben Meteoritenfragmenten die einzigen makroskopischen (mit bloßem Auge erkennbaren) Spuren eines Impakts. Sie entstehen durch den Einschlag von Meteoritenkörpern in Festgestein, wodurch es durch die Schockwellen strukturell verformt wurde. Die genaue Entstehung ist nicht vollständig geklärt. Akzeptiert ist, dass sie beim Durchlauf der Stoßwelle an einer Schwachstelle (z.B. Muschelschale, Inhomogenität) im Gestein entstehen. Beim Einschlagen eines Großmeteoriten in die Erdkruste werden die Gesteinsschichten im Bereich des Impaktkraters und in dessen näherer Umgebung extremen Druck und Temperaturverhältnissen ausgesetzt. In Bruchteilen einer Sekunde nach dem Impakt breitet sich, vom Einschlagkörper ausgehend, eine halbkugelförmige Druckwelle mit mehrfacher Schallgeschwindigkeit im Gestein aus. Das umgebende Gestein und auch der Einschlagkörper selbst werden dabei etwa auf ein Viertel ihres ursprünglichen Volumens komprimiert. Je nach Abstand vom Einschlagzentrum kommt es dabei zu spezifischen Veränderungen des Gestein wie Verdampfen, Aufschmelzen, Mineralumwandlung, mechanische Deformation und Zerbrechen.

Die nachfolgenden Bilder zeigen Strahlenkegel als Grafik und im Gelände.

Ks=Kegelspitze, Ps= Positivseite (konvexe Oberfläche), Ns= Negativseite (konkave Oberfläche)

Abb. Oberschwaben-portal.de

Strahlenkegel können in fast allen Gesteinsarten entstehen, sind aber in homogenen, feinkörnigen Gesteinen am deutlichsten ausgeprägt mit ihren Spitzen und strahlenartigen Brüchen. Bei grobkörnigen Gesteinen wie Graniten und Gneisen sind die Strahlenkegel meist grob und nicht sehr deutlich erkennbar. Die Größe der Kegel liegt im Impaktbereich im Zentimeter- bis Meterbereich.

Normalerweise zeigt die Kegelspitze, bei unveränderter primärer Lage im Gelände, in Richtung der Schockquelle, aber auch unregelmäßige Orientierung und sogar entgegengesetzte Ausrichtung können auftreten. Bei variierender Ausrichtung handelt es sich um sekundär gelagerte Strahlenkalke, also Gesteinsmaterial, welches während der Shatter-cones-Bildung noch umgelagert wurde. Mit Hilfe primär gelagerter Strahlenkegel ist eine Lokalisation der Einschlagstelle möglich, was enorm hilfreich ist, wenn der Krater heute nicht mehr vorhanden oder erkennbar ist.

In der Natur entstehen Shatter cones ausschließlich bei Impakt-Ereignissen (Einschläge von Stein-, Eisen- und Stein-Eisen-Meteoriten auf die Erdoberfläche) durch Stoßwellen und unter extrem hohem Druck zwischen 15 und 200 Kilobar. Außerdem konnte die Bildung von Shatter cones experimentell im Labor erzeugt werden. Auch in künstlich erzeugten Explosionskratern von Kernwaffentests wurden sie beobachtet. In Kratern vulkanischer Entstehung sowie in Gesteinen vulkanischer Herkunft wurden bislang nie Shatter cones festgestellt.

Eine mögliche Theorie

Strahlenkalke bzw. Shatter-Cones sind Produkte der Stoßwellen-Metamorphose und stellen heute eigenartige Leitgesteine bzw. -strukturen dar für die sichere Identifizierung von Impaktkratern. Das Vorhandensein der Strahlenkegel im Felsen von Gibraltar zeigt, dass es auch hier in der Umgebung in der Erdgeschichte Impakt-Ereignisse gegeben haben muss.

So wie die genaue Entstehung der Shatter cones noch nicht vollständig geklärt ist, gibt es auch verschiedene Theorien zur Entstehung der Straße von Gibraltar. Eine Theorie, welche zu den hier vorhandenen Shatter cones passen würde ist, dass die Meerenge durch zwei Meteoriteneinschläge verursacht wurde. Ein Impakt soll im westlichen Mittelmeer stattgefunden haben, der zweite 800 Kilometer nordwestlich vor der Nordküste Spaniens. Diese seismische Welle reichte bis zum Mittelmeer. Dieses Ereignis fand vor 5,33 Millionen Jahren statt. Auch auf dem Meeresboden der Region um die Einschläge sollen noch einige Wellen erkennbar sein, die durch die seismischen Schockwellen entstanden sind.

Schaut euch die Strukturen im Kalkstein genau an und beantwortet dann bitte vor dem Loggen folgende Fragen!

1. Wieviele Shatter cones konntet ihr auf der gesamten Wegstrecke finden?

2. Beschreibt eure gefundenen Strahlenkegel (Durchmesser, vollständig runde Ausprägung oder nur teilweise)!

3. Ist die Spitze aller Shatter cones gleich ausgerichtet oder gab es eurer Meinung nach sekundäre Umlagerungen?

4. Findet ihr die Strukturen in konvexer oder konkaver Form oder gibt es hier beide Formen?

5. Macht ein Foto von euch mit einem Strahlenkegel und hängt es an Euren Log!

Schickt eine Mail mit euren Antworten an mich! Nach dem Absenden der Antworten könnt ihr gleich loggen. Falls etwas nicht in Ordnung ist, melde ich mich. Ihr braucht nicht die Logfreigabe abwarten! Ich wünsche euch viel Spaß bei dieser geologischen Entdeckungsreise!

Quellen: mineralienatlas.de, wikipedia, oberschwaben-portal.de, geozentrum-hannover.de, impaktstrukturen.de, marineinsight.com