Manoir Landren

Manoir Landren

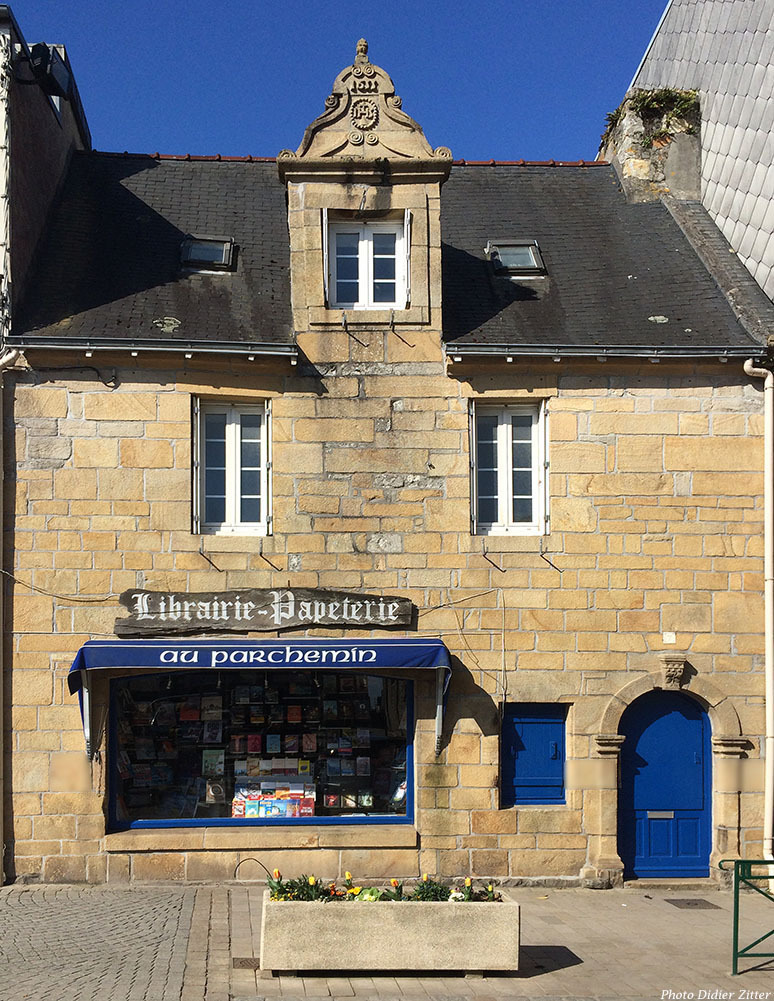

Des maisons de nobles sont situées dans le bourg de Crozon, autour de l'église et ont pour signe distinctif la voûte de la porte en pierre elle aussi dite noble, c'est à dire en pierre du Roz (jaune, ocre) ou pierre de Kersanton (grise) plus ou moins sculptée.

Des maisons de nobles sont situées dans le bourg de Crozon, autour de l'église et ont pour signe distinctif la voûte de la porte en pierre elle aussi dite noble, c'est à dire en pierre du Roz (jaune, ocre) ou pierre de Kersanton (grise) plus ou moins sculptée.

Le manoir Landren est un des manoirs de la ville de Crozon. Il est situé rue de Reims, face à l’église St-Pierre et aurait appartenu à la famille Landren de Dirinon. Sa construction est datée de 1655. Il s’agit de la seule habitation de la commune entièrement construite en pierre du Roz.

Au travers de cette cache, nous vous proposons d’aller à la découverte de cette pierre et quelques unes de ses caractéristiques.

Landren manor

Landren manor

Some noble houses are located in the borough of Crozon, around the church and have for distinctive sign the vault of the door in stone also called noble, that is to say in Le Roz stone (yellow) or Kersanton stone (grey) more or less sculpted.

The Landren manor is one of the manors of the city of Crozon. It is in rue de Reims, in front of the St-Pierre church and would have belonged to the Landren de Dirinon family . Its construction is dated 1655. It's the only house in the town entirely built in Le Roz stone.

Through this cache, we propose you to go to the discovery of this stone and one of its features.

Quelques concepts - Few concepts

Roches

Roches

Trois types de roches forment principalement l’écorce terrestre : les roches sédimentaires constituées de sédiments meubles qui se sont transformés (consolidés) au cours de l’évolution géologique ; les roches ignées (ou magmatiques) qui résultent de la solidification du magma, roche fondue sous l'action de la chaleur et de la pression dans les couches profondes de l'écorce terrestre ou dans la couche supérieure du manteau ; les roches métamorphique issues d’une une transformation à l'état solide de roches sédimentaires, ignées ou… métamorphiques et provoquée par une modification de pression, de température…

Trois types de roches forment principalement l’écorce terrestre : les roches sédimentaires constituées de sédiments meubles qui se sont transformés (consolidés) au cours de l’évolution géologique ; les roches ignées (ou magmatiques) qui résultent de la solidification du magma, roche fondue sous l'action de la chaleur et de la pression dans les couches profondes de l'écorce terrestre ou dans la couche supérieure du manteau ; les roches métamorphique issues d’une une transformation à l'état solide de roches sédimentaires, ignées ou… métamorphiques et provoquée par une modification de pression, de température…

Rocks

Rocks

There are three main types of rocks which constitute the earth's crust: sedimentary rocks made up of loose unconsolidated sediment that have been transformed into rock during geological history; igneous (or magmatic) rocks, the product of the solidification of magma, which is molten rock generated by partial melting caused by heat and pressure in the deeper part of the Earth's crust or in the upper mantle; metamorphic rocks resulting from a transformation to a solid state of sedimentary, igneous or... metamorphic rocks and caused by a change of pressure, temperature...

- - -

Pierre du Roz

Pierre du Roz

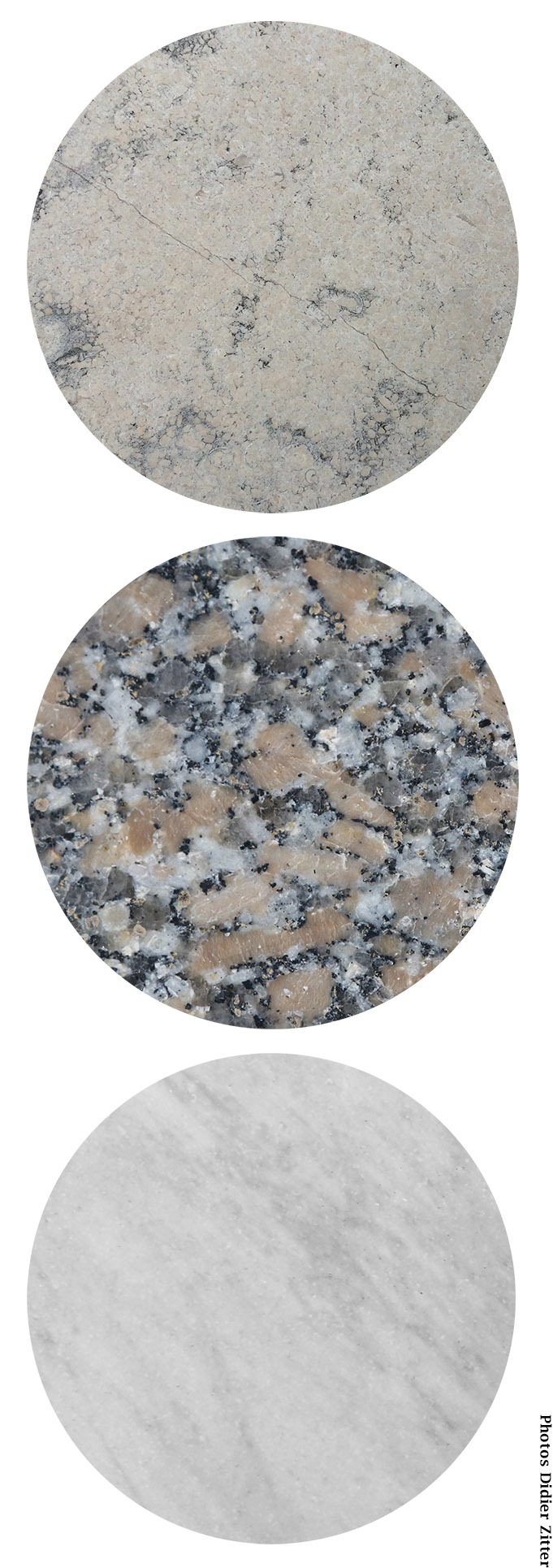

La pierre du Roz (lieu-dit Le Roz - commune de Logonna-Daoulas) encore appelée pierre de Logonna, est une roche ignée apparentée au granite. Cependant, sa texture grenue est bien plus fine (presque invisible à l’oeil nu) que celle du ou des granites. Il s’agit plus précisément d’une microgranodiorite aussi classée, selon la littérature, en microgranite encore en microdiorite quartzique microgrenue !

La pierre du Roz (lieu-dit Le Roz - commune de Logonna-Daoulas) encore appelée pierre de Logonna, est une roche ignée apparentée au granite. Cependant, sa texture grenue est bien plus fine (presque invisible à l’oeil nu) que celle du ou des granites. Il s’agit plus précisément d’une microgranodiorite aussi classée, selon la littérature, en microgranite encore en microdiorite quartzique microgrenue !

Comme tous les microgranites ou les roches microgrenues, elle est le produit d’un refroidissement rapide d’un magma qui n’a pas subi l’éruption. On trouve la pierre du Roz sous terre en forme de filons, apparus plus tard à la surface de la terre suite à des mouvements tectoniques et/ou suite à l'érosion des roches qui les recouvrent.

Son aspect parfois alvéolaire, ou présentant des petits trous, provient de l’altération d’un des minéraux appelé biotite (de teinte sombre). Le fer oxydé, présent dans les feldpaths qui constituent en partie cette roche, donne à la pierre du Roz une couleur jaune-ocre.

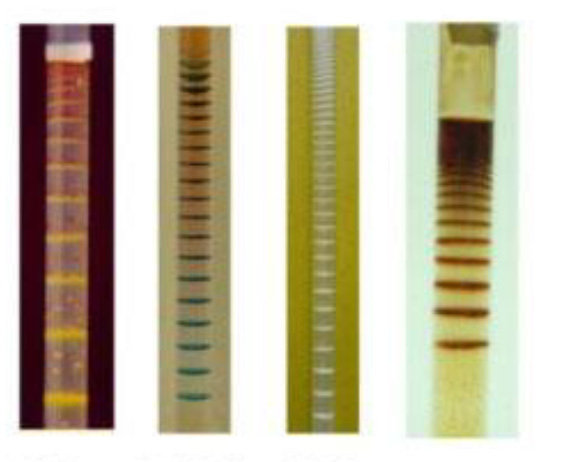

Très souvent, des auréoles, des cercles concentriques ou parfois des bandes d’une couleur brunâtre sont visibles à la surface de cette pierre. Ce phénomène, apparenté aux bandes ou anneaux de Liesegang (du nom du chimiste allemand qui les a observé pour la première fois), provient de la migration du fer sous forme d’oxyde provoquée par la circulation d’eau dans la roche.

Le Roz stone

Le Roz stone

Le Roz stone (place called Le Roz - commune of Logonna-Daoulas) also called Logonna stone, is an igneous rock related to granite. However, its grained texture is much finer (almost invisible to the naked eye) than that of the granite(s). It’s more precisely a microgranodiorite also classified, according to the literature, as microgranite or microdiorite quartz micrograined!

Le Roz stone (place called Le Roz - commune of Logonna-Daoulas) also called Logonna stone, is an igneous rock related to granite. However, its grained texture is much finer (almost invisible to the naked eye) than that of the granite(s). It’s more precisely a microgranodiorite also classified, according to the literature, as microgranite or microdiorite quartz micrograined!

Like all microgranites or micrograined rocks, it’s the product of a rapid cooling of magma that has not erupted. Le Roz stone is found underground in the form of veins, which appeared later on the surface of the earth as a result of tectonic movements and/or the erosion of the rocks that cover them.

Its appearance sometimes alveolar, or having small holes, comes from the weathering of one of the minerals called biotite (dark shade). Oxidized iron, contained in feldpaths which partly constitute this rock, gives Le Roz stone a yellow-ochre color.

Very often, halos, concentric circles or sometimes bands of a brownish color are visible on the surface of this stone. This phenomenon, related to Liesegang banding or rings (from the name of the German chemist who observed it for the first time), comes from the migration of iron in the form of oxide due to water circulation in the rock.

- - -

Formation de motifs

Formation de motifs

En 1952, Alan Turing publia son célèbre article «The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis » dans lequel il avance une idée originale : la morphogenèse serait causée par la perte de stabilité, due à la diffusion, d’une position d’équilibre de réactants chimiques. En d’autres termes, des équations de réaction-diffusion pourraient modéliser un pelage tacheté, rayé ou bien plus complexe encore. Bien que les biologistes n’aient actuellement pas la technologie nécessaire pour confirmer l’hypothèse d’Alan Turing, certains motifs obtenus grâce aux modélisations sont si proches de la réalité que cette hypothèse semble être une des explications les plus prometteuses.

En 1952, Alan Turing publia son célèbre article «The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis » dans lequel il avance une idée originale : la morphogenèse serait causée par la perte de stabilité, due à la diffusion, d’une position d’équilibre de réactants chimiques. En d’autres termes, des équations de réaction-diffusion pourraient modéliser un pelage tacheté, rayé ou bien plus complexe encore. Bien que les biologistes n’aient actuellement pas la technologie nécessaire pour confirmer l’hypothèse d’Alan Turing, certains motifs obtenus grâce aux modélisations sont si proches de la réalité que cette hypothèse semble être une des explications les plus prometteuses.

La formation de motifs est un processus dynamique limité dans le temps qui se produit dans différents contextes et au cours duquel des motifs ou des structures périodiques se forment de manière autonome, après qu'un état initialement homogène dans l'espace est devenu instable,

Pattern formation

Pattern formation

In 1952, Alan Turing published his famous article "The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis" in which he suggested an original idea: morphogenesis would be the result of the loss of stability, due to diffusion, of a position of equilibrium of chemical reactants. In other words, reaction-diffusion equations could model a spotted, striped or even more complex coat. Although biologists do not currently have the technology to confirm Alan Turing's hypothesis, some of the patterns obtained through modeling are so close to reality that this hypothesis seems to be one of the most exciting explanations.

Pattern formation is a time-limited dynamic process occurring in various contexts, in which periodic patterns or structures form independently after an originally spatially homogeneous state has previously become unstable,

- - -

Système à réaction-diffusion

Système à réaction-diffusion

Un système à réaction-diffusion est un modèle mathématique qui décrit l'évolution des concentrations d'une ou plusieurs substances spatialement distribuées et soumises à deux processus : un processus de réactions chimiques locales, dans lequel les différentes substances se transforment, et un processus de diffusion qui provoque une répartition de ces substances dans l'espace. De tels systèmes sont appliqués en chimie. Cependant, ils peuvent aussi décrire des phénomènes dynamiques de nature différente : la biologie, la physique, la géologie ou l'écologie sont des exemples de domaines où de tels systèmes apparaissent.

Reaction-diffusion system

Reaction-diffusion system

A reaction-diffusion system is a mathematical model that describes the evolution of the concentrations of one or more substances spatially distributed and subject to two processes: a process of local chemical reactions, in which the different substances are transformed, and a diffusion process that causes a distribution of these substances in space. Such systems are applied in chemistry. However, they can also describe dynamic phenomena of a different nature: biology, physics, geology or ecology are examples of fields where such systems appear.

- - -

Précipitation et précipité

Précipitation et précipité

Une précipitation correspond à la formation, dans une solution, d’un composé solide à partir d’une ou plusieurs substances chimiques initialement dissoutes. Le composé solide qui se forme lors d’une précipitation est qualifié de « précipité », il peut se présenter sous forme de cristaux se déposant au fond du récipient ou sur les parois (vaporisation d’une eau salée) mais il peut aussi prendre l’apparence d’une substance gélatineuse constituée de minuscules particules solides dispersées dans l’eau.

Une précipitation correspond à la formation, dans une solution, d’un composé solide à partir d’une ou plusieurs substances chimiques initialement dissoutes. Le composé solide qui se forme lors d’une précipitation est qualifié de « précipité », il peut se présenter sous forme de cristaux se déposant au fond du récipient ou sur les parois (vaporisation d’une eau salée) mais il peut aussi prendre l’apparence d’une substance gélatineuse constituée de minuscules particules solides dispersées dans l’eau.

Une précipitation a lieu lorsque les concentrations des substances chimiques dissoutes dans une solution excèdent l’une des valeurs de solubilité. Cette situation peut se présenter :

- suite à une variation de concentration des substances chimiques dissoutes

- suite à une variation de la solubilité elle-même

- en raison de l’introduction de nouvelles substances chimiques en solution

Precipitation and precipitate

Precipitation and precipitate

A precipitation consists of the formation, in a solution, of a solid compound from one or more initially dissolved chemical substances. The solid compound that forms during precipitation is called "precipitate", it can be in the form of crystals deposited at the bottom of the container or on the walls (vaporization of salt water) but it can also take the appearance of a gelatinous substance made up of tiny solid particles dispersed in the water.

Precipitation occurs when the concentrations of dissolved chemicals in a solution exceed one of the solubility values. This situation can occur:

- as a result of a variation in the concentration of the dissolved substances

- due to a variation in the solubility itself

- due to the introduction of new chemical substances in solution

- - -

Bandes ou anneaux de Liesegang

Bandes ou anneaux de Liesegang

La formation de motifs la plus ancienne est le phénomène ou effet de Liesegang (ou précipitation périodique), qui a été découvert et décrit par Raphael Eduard Liesegang, un chimiste et photographe allemand.

La formation de motifs la plus ancienne est le phénomène ou effet de Liesegang (ou précipitation périodique), qui a été découvert et décrit par Raphael Eduard Liesegang, un chimiste et photographe allemand.

En 1896, Raphael Liesegang, en déposant une goutte de nitrate d'argent sur du bichromate de potassium dans la gélatine, découvre que la précipitation se produit sous formes d'anneaux concentriques appelés depuis anneaux de Liesegang.

Il s’agit de bandes parallèles de précipité formées par diffusion avec une répartition inégale du précipité en fonction de la distance (gradient de concentration/chimique) au cours d'un événement unique.

En milieu contrôlé, ces bandes/anneaux apparaissent en quelques heures à quelques jours et sont distribuées selon les lois d’échelle suivantes :

- loi d’espacement : la position des bandes/anneaux suit une progression géométrique et l’espacement entre les bandes/anneaux s’accroit ;

- loi de largeur : la largeur des bandes augmente avec la distance.

Au cours des 120 dernières années, de nombreuses théories ont été avancées pour tenter d’expliquer la formation de ces anneaux ou ces bandes. Une des avancées les plus récentes (2020) explore des modèles de pré-nucléation et de post-nucléation sans pouvoir avancer un modèle standard unifié.

Liesegang banding or rings

Liesegang banding or rings

The oldest pattern formation is the Liesegang phenomenon (or periodic precipitation), which was discovered and describedby Raphael Eduard Liesegang, German chemist and photographer.

The oldest pattern formation is the Liesegang phenomenon (or periodic precipitation), which was discovered and describedby Raphael Eduard Liesegang, German chemist and photographer.

In 1896, Raphael Liesegang by depositing a drop of silver nitrate on potassium dichromate in gelatin discovered that precipitation occurs in the form of concentric rings, since then called Liesegang rings.

It consists of parallel bands of precipitate formed by diffusion with an uneven distribution of precipitate as a function of distance (concentration/chemical gradient) during a single event.

In a controlled environment, these bands/rings appear within hours to days and are scaled according to the following laws:

- law of spacing: the position of the bands/rings follows a geometrical progression and the spacing between the bands/rings increases;

- width law: the width of the bands/rings increases with the distance.

Over the last 120 years, many theories have been put forward to try to explain the formation of these rings or bands. One of the most recent advances (2020) explores pre-nucleation and post-nucleation models without being able to advance a unified standard model.

- - -

Ion, anion et cation

Ion, anion et cation

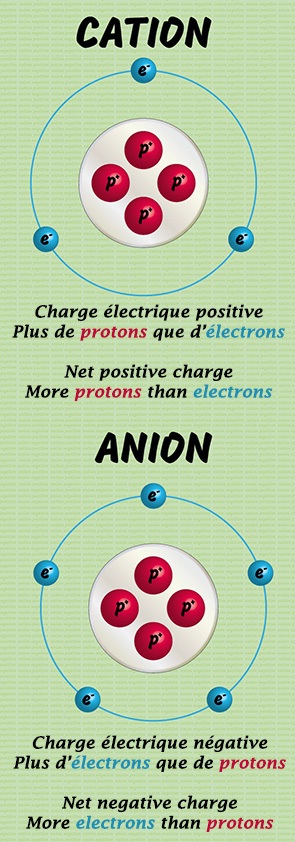

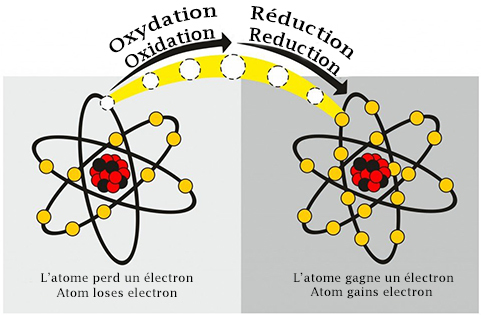

Dans un atome neutre, le nombre de protons = le nombre d'électrons. Un ion est un atome, ou un groupe d'atomes, ayant perdu ou gagné un ou plusieurs électrons.

Un anion est un atome (ou une molécule) qui a gagné un ou plusieurs électrons. Comme l'électron est chargé négativement, l'anion porte une charge négative. Il s’agit donc d’un ion négatif.

À l'inverse, un cation est un atome (ou une molécule) qui a perdu un ou plusieurs électrons. La charge électrique globale du cation est donc positive. Il s’agit donc d’un ion positif.

Les ions sont notés en tenant compte de la différence entre le nombre de protons et le nombre d'électrons. Dans la version « simple », on écrira Xn+ et Xn- pour respectivement, un ion qui porte une charge positive (cation) car plus de protons que d’électrons et un ion qui porte une charge négative (anion) car moins de protons que d’électron. Ex : Na+ ou OH- (on n’écrit pas n=1).

Ion, anion and cation

Ion, anion and cation

In a neutral atom, the number of protons = the number of electrons. An ion is an atom, or a group of atoms, that has lost or gained one or more electrons.

An anion is an atom (or a molecule) that has gained one or more electrons. As the electron is negatively charged, the anion has a negative charge. It is therefore a negative ion.

Conversely, a cation is an atom (or molecule) that has lost one or more electrons. The overall electrical charge of the cation is therefore positive. It is therefore a positive ion.

Ions are noted by taking into account the difference between the number of protons and the number of electrons. In the "basic" version, we write Xn+ and Xn- for respectively, an ion that carries a positive charge (cation) because it has more protons than electrons and an ion that carries a negative charge (anion) because it has less protons than electrons. Ex : Na+ or OH- (we do not write n=1).

- - -

Oxydation, réduction, nombre d’oxydation, oxydant, réducteur et … patati et patata !

Oxydation, réduction, nombre d’oxydation, oxydant, réducteur et … patati et patata !

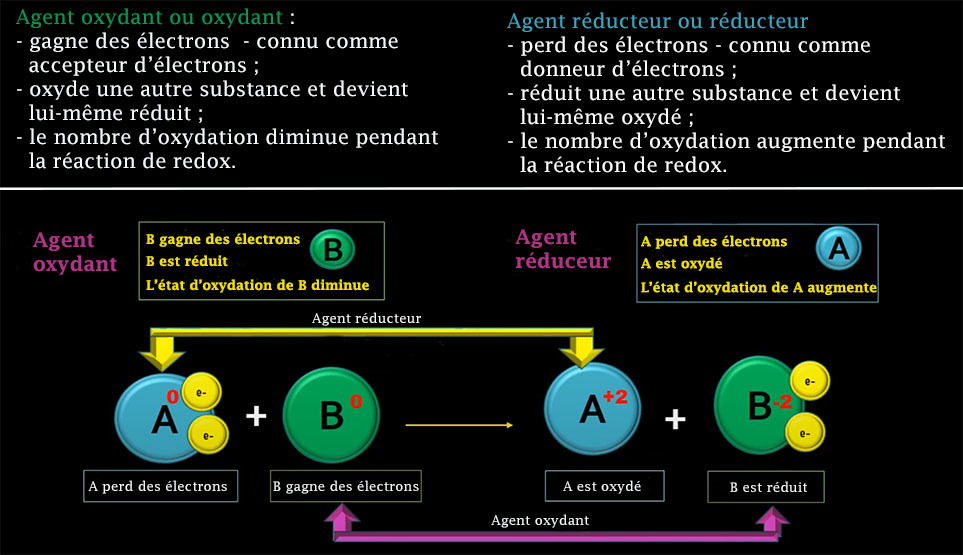

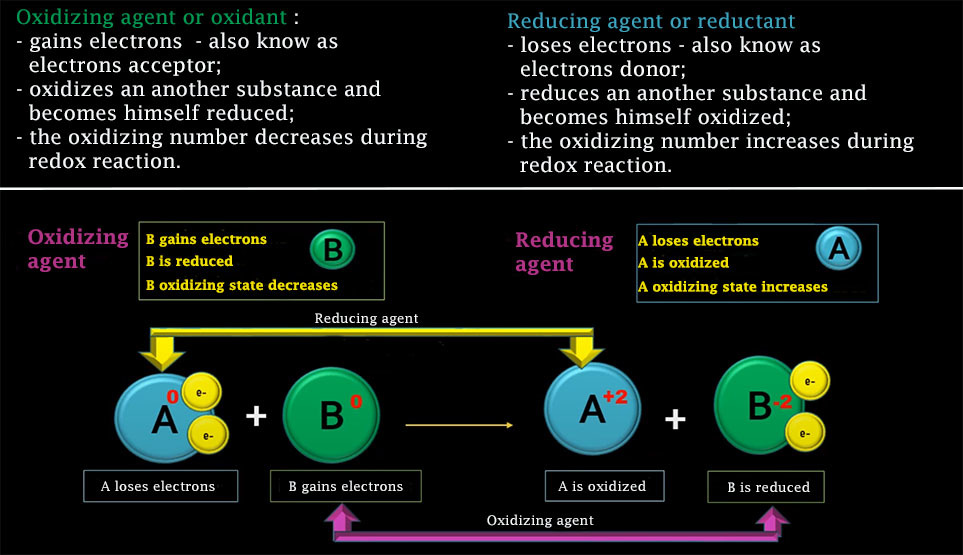

L'oxydation est un phénomène courant ; une pomme brunie ou un clou rouillé sont deux exemples courants de réactions d'oxydation. L'oxydation ne signifie pas qu'un atome d'oxygène est ajouté au composé. Il s'agit plutôt d'une réaction chimique qui implique la perte d'électrons.

L'oxydation est un phénomène courant ; une pomme brunie ou un clou rouillé sont deux exemples courants de réactions d'oxydation. L'oxydation ne signifie pas qu'un atome d'oxygène est ajouté au composé. Il s'agit plutôt d'une réaction chimique qui implique la perte d'électrons.

Cet électron perdu ne se promène pas sans but dans l'univers ; il est pris en charge par un autre atome. Lorsqu'un atome accepte un électron, il s'agit d'une réaction de réduction. L'oxydation et la réduction vont de pair et sont appelées conjointement des réactions d'oxydoréduction (souvent appelées redox).

Le nombre d'oxydation, également appelé état d'oxydation, est le nombre total d'électrons qu'un atome gagne ou perd afin de former une liaison chimique avec un autre atome.

Les atomes neutres isolés (corps à l’état élémentaire) ont par définition un nombre d’oxydation nul. Si un atome donne (perd) un électron, on dit qu'il a un nombre d'oxydation (n.o.) égal à un +I ; s'il en donne deux, n.o. = +II, etc. Réciproquement, si un atome accepte (reçoit) un électron, son nombre d'oxydation devient -I ; s'il en accepte deux, n.o. = −II, etc.

Le nombre d’oxydation maximal est +VII et le nombre minimal est –II.

Un oxydant, ou agent oxydant ou agent d'oxydation, est un corps simple, un composé ou un ion qui reçoit au moins un électron d'une autre espèce chimique lors d'une réaction d'oxydoréduction. L'oxydant ayant accepté au moins un électron au cours de cette réaction est dit réduit, tandis que l'espèce chimique qui a cédé au moins un électron est dite oxydée. Un oxydant est généralement proche de son état d'oxydation le plus élevé et se comporte par conséquent comme un accepteur d'électron.

Un réducteur est un corps simple, un composé ou un ion qui cède au moins un électron à une autre espèce chimique lors d'une réaction d'oxydoréduction. Le réducteur ayant perdu au moins un électron au cours de cette réaction est dit oxydé, tandis que l'espèce chimique qui a reçu au moins un électron est dite réduite. Un réducteur est généralement proche de son état d'oxydation le plus faible et se comporte par conséquent comme un donneur d'électron.

Les métaux sont généralement considérés comme des éléments qui peuvent facilement perdre des électrons, ils sont donc connus pour être facilement oxydés.

Oxidation, reduction, oxidation number, oxydant, reductant and do on and so forth

Oxidation, reduction, oxidation number, oxydant, reductant and do on and so forth

Oxidation is a common phenomenon; a browned apple or a rusty nail are both common examples of oxidation reactions. Oxidation does not mean that an oxygen atom is added to the compound. Instead, it is a chemical reaction that involves the loss of electrons.

This lost electron does not wander around in the universe aimlessly; it is taken up by another atom. When one atom accepts an electron, it is called a reduction reaction. Oxidation and reduction go hand-in-hand and are jointly referred to as redox reactions.

The oxidation number, also called the oxidation state, is the total number of electrons that an atom gains or loses in order to form a chemical bond with another atom.

Isolated neutral atoms (elementary material) have by definition an oxidation number of zero. If an atom gives (loses) one electron, it is said to have an oxidation number ( o.n.) equal to +I; if it gives two, o.n. = +II, etc. Reversely, if an atom accepts (receives) an electron, its oxidation number becomes -I; if it accepts two, n.o. = -II, etc.

The maximum oxidation number is +VII and the minimum is -II.

An oxidizing agent, or oxidant, is a simple body, compound or ion that receives at least one electron from another chemical species during a redox reaction. The oxidant agent that has accepted at least one electron during this reaction is said to be reduced, while the chemical species that has given up at least one electron is said to be oxidized. An oxidant agnet is usually close to its highest oxidation state and therefore behaves as an electron acceptor.

A reducing agent, or reductant, is a simple body, compound or ion that gives up at least one electron to another chemical species in a redox reaction. The reductant that has lost at least one electron during this reaction is said to be oxidized, while the chemical species that has received at least one electron is said to be reduced. A reducing agent is generally close to its weakest oxidation state and therefore behaves like an electron donor.

Metals are generally considered to be elements that can easily lose electrons, so they are known to be easily oxidized.

- - -

Le fer

Le fer

Le fer, un métal de symbole chimique Fe, est l’un des éléments les plus abondants de la croûte terrestre. Il existe sous plusieurs formes de degré d'oxydation allant de -II à +VII ; cependant, il est principalement présent sous forme +II ou +III.

Le fer, à l’état naturel, existe donc sous deux formes oxydées :

- l’oxyde de fer(II) appelé aussi « fer ferreux », noté Fe(II) mais aussi Fe2+ pour l’ion ferreux. Il est souvent présent sous forme soluble (comme le sucre ou le sel dans l’eau) dans les roches et l’acidité de la roche favorise sa solubilité.

- l’oxyde de fer(III) appelé aussi « fer ferrique » ; noté Fe(III) mais aussi Fe3+pour l’ion ferrique. Il est très rarement présent sous forme soluble dans les roches.

Fe(II) et Fe(III) n'existent pas seuls, mais au sein d'une molécule : Fe3O4, Fe2CO3, FeS2 ...

On peut aussi le trouver sous forme métallique - Fe(0) - qui est le résultat d’un fer transformé par les activités humaines à partir de minerais de fer.

Iron

Iron

Iron, chemical symbol Fe, is one of the most abundant elements in the earth's crust. It exists in several forms of oxidation degree going from -II to +VII; however, it is mainly present in the +II or +III form.

Iron, in its natural state, exists in two oxidized forms:

- iron(II) oxide also called "ferrous iron", noted Fe(II) but also Fe2+ for ferrous ion. It is often present in soluble form (like sugar or salt in water) in rocks and the acidity of the rock favors its solubility.

- Iron(III) oxide also called "ferric iron"; noted Fe(III) but also Fe3+ for ferric ion. It is very rarely found in soluble form in rocks.

Fe(II) and Fe(III) do not exist alone, but within a molecule: Fe3O4, Fe2CO3, FeS2 ...

It can also be found in metallic form - Fe(0) – which is the result of iron transformed by human activities from iron ores.

- - -

Propriétés d'oxydoréduction de l'eau

Propriétés d'oxydoréduction de l'eau

Dans une molécule d'eau H2O, l'oxygène est au nombre d'oxydation -II et l'hydrogène au nombre d'oxydation +I. H2O est à la fois un oxydant faible (réduction de H+ en H2) et un réducteur faible (oxydation OH− en O2).

Dans une molécule d'eau H2O, l'oxygène est au nombre d'oxydation -II et l'hydrogène au nombre d'oxydation +I. H2O est à la fois un oxydant faible (réduction de H+ en H2) et un réducteur faible (oxydation OH− en O2).

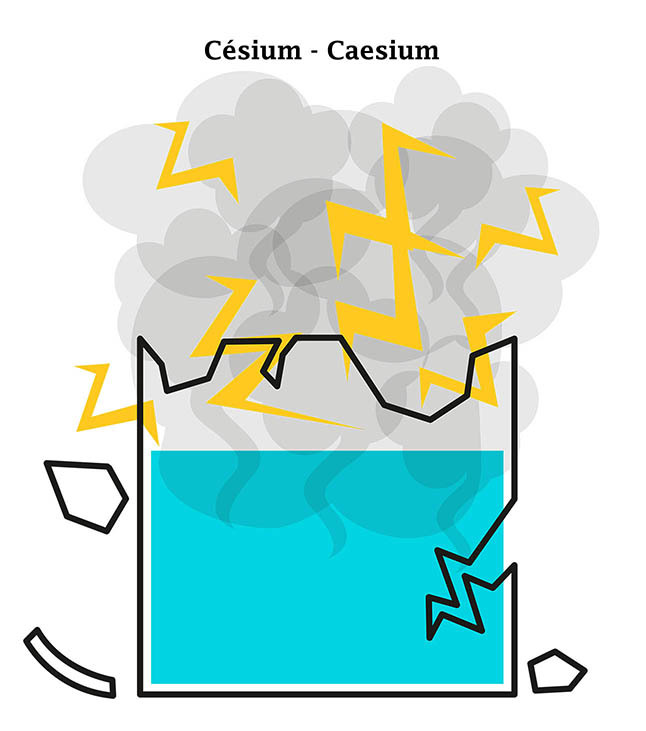

Le contact entre l’eau et le fer va provoquer des réactions d’oxydoréduction, dont le résultat pour du fer métallique – Fe(0) – est l’apparition de la rouille (suivant une période plus ou moins longue). Cependant, le contact entre l’eau et un métal alcalin (lithium, sodium, potassium, césium, ..) qui a un fort « penchant » réducteur (donc donner/perdre des électrons) va provoquer une réaction d’oxydoréduction immédiate et parfois vraiment très spectaculaire (boum… au feu) !

Redox properties of water

Redox properties of water

In a water molecule H2O, oxygen is at oxidation number -II and hydrogen at oxidation number +I. H2O is both a weak oxidant (reduction of H+ to H2) and a weak reductant (oxidation of OH- to O2).

Water in contact with iron will cause redox reactions, which result in rusting of metallic iron - Fe(0) - over a longer or shorter period. However, contact between water and an alkaline metal (lithium, sodium, potassium, caesium, ...) which has a strong reducing "tendency" (thus giving/losing electrons) will cause an immediate and sometimes really very spectacular redox reaction (boom... fire)!

- - -

Migration et précipitation du fer au sein de la pierre de Roz

Migration et précipitation du fer au sein de la pierre de Roz

Après le refroidissement assez rapide d’un magma, remonté sous forme de filon mais sans subir l’éruption, de l’eau va sans doute circuler au sein de la roche en empruntant des canaux de porosité altérée ou des microfissures au sein de cette roche.

La circulation ou la stagnation de cette eau va provoquer, grâce au pouvoir oxydant de l’oxygène qu’elle contient, la précipitation du fer ferreux – Fe(II) – dissous dans la roche qui apparaîtra sous forme de fer ferrique – Fe(III) – (de l’hydroxyde de fer) totalement insoluble formant une mince bande couleur rouille.

Un peu plus loin dans la roche, le fer ferreux – Fe(II) – est en toujours en partie dissout et les germes d’oxyde ferrique – Fe(III) – déjà formés (par précipitation) dans la première couche attirent à eux les ions Fe2+ libérés qui s’oxydent puis précipitent et participent ainsi à un phénomène de croissance. La bande oxydée est renforcée puisque la concentration en fer y devient supérieure à celle de la roche tandis que la zone située immédiatement à l’arrière est appauvrie en fer et se transforme ainsi en bande ou anneau de couleur plus claire.

Au-delà de cette bande ou anneau, le phénomène recommence conduisant à la formation d’une succession de « couches » de couleur brun sombre et beige plus pale.

Les formes obtenues ne seront jamais parfaites. Elles se formeront en fonction des structures d’alimentation en eau et des variations de porosité de la roche. Elles seront donc totalement irrégulières.

Le résultat est donc une succession de bandes brunes d’ordre millimétrique ou centimétrique alternativement claires et foncées. Il suffit de casser un bloc pour se rendre compte que le phénomène n’est pas superficiel, mais qu’il affecte la roche en profondeur, dans ses trois dimensions. Ces auréoles ne sont pas un phénomène rare dans la nature et leur présence autour de petites fissures est même fréquente dans des roches très variées.

Ce processus n’est pas réalisé en quelques minutes, heures ou jours.

Migration and precipitation of iron in the Roz stone

Migration and precipitation of iron in the Roz stone

After the quite rapid cooling of a magma, brought up in the form of a vein but without undergoing the eruption, water will undoubtedly move through the rock by following channels of altered porosity or micro-cracks in the rock.

The flow or stagnation of this water will induce, because of the oxidizing power of oxygen it contains, the precipitation of ferrous iron - Fe(II) - dissolved in the rock which will appear as ferric iron - Fe(III) - (iron hydroxide) totally insoluble forming a thin rust-colored band.

A little further in the rock, the ferrous iron - Fe(II) - is still partly dissolved and the ferric oxide - Fe(III) - seeds already formed (by precipitation) in the first layer draw to them released Fe2+ ions which oxidize and then precipitate and so participate to a growing process. The oxidized band is strengthened since the concentration of iron becomes higher than that of the rock, while the zone immediately behind it is reduced in iron and becomes a band or ring of lighter color.

Beyond this band or ring, the process starts again leading to the formation of a succession of dark brown and pale beige "layers".

The shapes resulting from this process will never be perfect. They will be formed according to the structures of water feeding and the variations of porosity of the rock. They will therefore be totally irregular.

The result is a succession of brown bands of millimeter or centimeter order alternately clear and dark. Just break a block to realize that the process is not superficial, but it affects the rock in depth, in its three dimensions. These rings are not a rare occurrence in nature and their existence around small cracks is even common in a wide variety of rocks.

This process does not take place in few minutes, hours or days.

Références - References

Le Paléozoïque de la presqu’île de Crozon, Massif Armorican

Kersantites and associated intrusives from the type locality (Kersanton)

La formation de motifs et l’instabilité de Turing

Système à réaction-diffusion

La précipitation

Difference betweeen oxidizing agent and reducing agent

Pattern Formation in Precipitation Reactions: The Liesegang Phenomenon

Caracterisation of the geometric distribution of Liesegang's phenomena in chalk

Pour valider la cache - Logging requirements

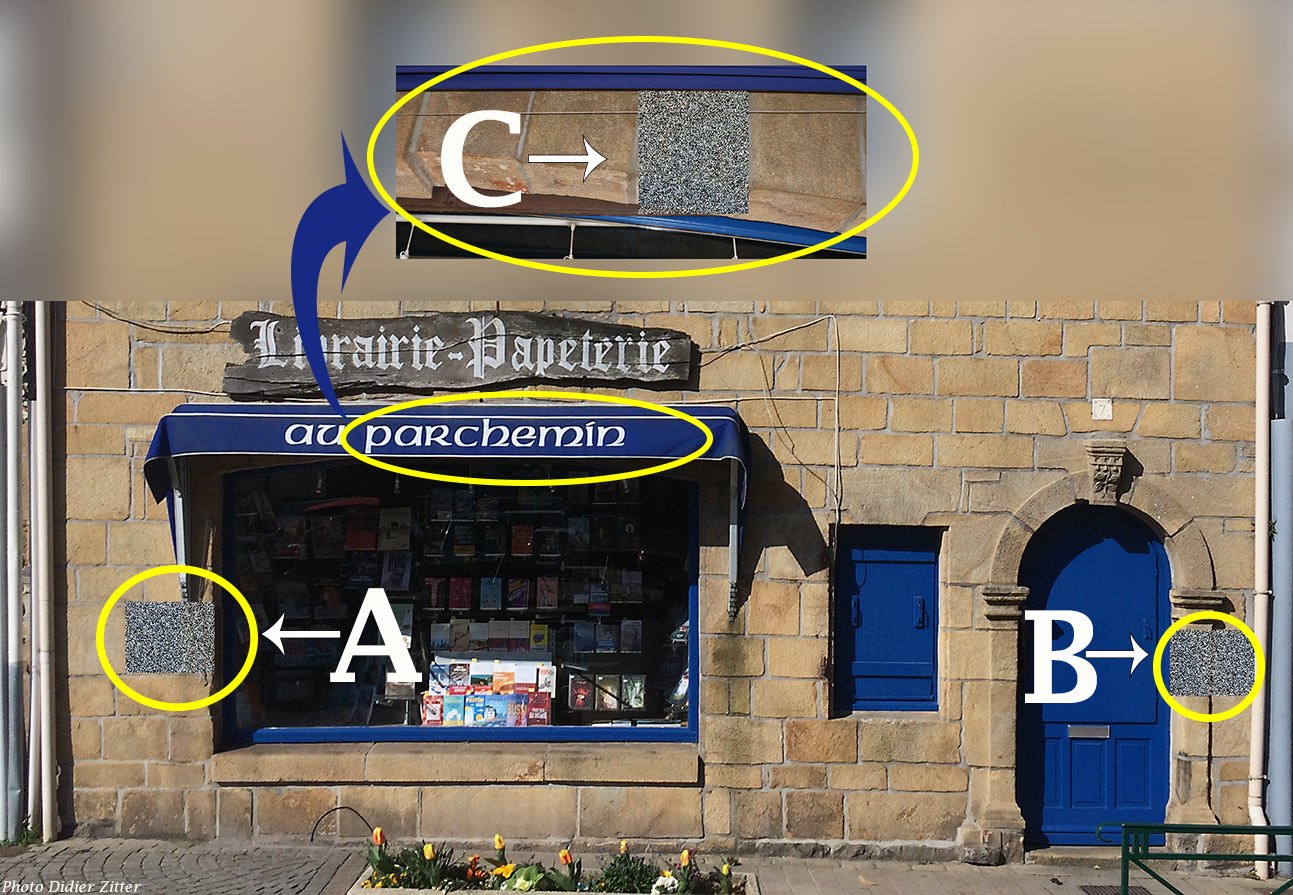

Aux coordonnées indiquée, faites face à la librairie, observez sa façade comme sur la photo ci-dessous et avancez près de la vitrine pour observer le linteau caché par l’auvent. Certaines pierres ont été masquées.

Aux coordonnées indiquée, faites face à la librairie, observez sa façade comme sur la photo ci-dessous et avancez près de la vitrine pour observer le linteau caché par l’auvent. Certaines pierres ont été masquées.

At the coordinates indicated, face the bookstore, look at its facade as in the picture below and move near the window to observe the lintel hidden by the awning. Some stones have been covered.

At the coordinates indicated, face the bookstore, look at its facade as in the picture below and move near the window to observe the lintel hidden by the awning. Some stones have been covered.

Travail à effectuer

Travail à effectuer

- Observez les pierres A et B. Décrivez ce que vous voyez. Quelle(s) différence(s) notable(s) remarquéz-vous à propos des motifs apparentés à l'effet Liesegang présents sur ces deux pierres ?

- Observez les pierres B et C. Hormis les formes, le nombre, la coloration, l'épaisseur, l'espacement, etc. des motifs, quelle est la caractéristique commune à ces motifs qui peut être vérifiée ?

- Selon vous, pourrait-on avancer que ces motifs sont issues, ou non, de l'effet Liesegang, et pour quelle raison ?

- Une photo de vous, ou d’un objet caractéristique vous appartenant, prise dans les environs immédiats (pas de photo « d’archive » svp) est à joindre soit en commentaire, soit avec vos réponses. Conformément aux directives mises à jour par GC HQ et publiées en juin 2019, des photos peuvent être exigées pour la validation d'une earthcache.

Marquez cette cache « Trouvée » et envoyez-nous vos propositions de réponses en précisant bien le nom de la cache, soit via notre profil, soit via la messagerie geocaching.com (centre de messagerie) et nous vous répondrons en cas de problème. « Trouvée » sans réponses sera supprimée.

- - -

Homework

Homework

- Look at stones A and B. Describe what you see. What notable difference(s) do you notice about the Liesegang-like patterns on these two stones?

- Look at stones B and C. Apart from the shapes, number, coloration, thickness, spacing, etc. of the patterns, what is the common characteristic of these patterns that can be verified?

- In your opinion, could it be argued that these patterns are or are not the result of the Liesegang effect, and for which reason?Look at stones A and B. Describe what you see. What notable difference(s) do you notice about the Liesegang-like patterns on these two stones?

- A photo of your, your GPS or something else personal taken in the immediate aera (no "stock" photos please) is to be attached either as a comment or with your answers. In accordance with updated GC HQ guidelines published in June 2019, photos may be required for validation of an earthcache.

Log this cache "Found it", and send us your answers, don't forget to mention the name of the cache, via our profile or via geocaching.com (Message Center) and we will contact you in case of any problemes. "Found it" without the anwers will be deleted.