Tour Eiffel : d'où provient le fer ? - Eiffel Tower: where does the iron come from?

La tour Eiffel est un monument emblématique de Paris. Elle a été construite pour l’Exposition universelle de 1889 sous la direction de Gustave Eiffel, ingénieur et industriel.

La tour Eiffel est un monument emblématique de Paris. Elle a été construite pour l’Exposition universelle de 1889 sous la direction de Gustave Eiffel, ingénieur et industriel.

Il s’agit d’une tour initialement de 301 mètres de haut (330 de nos jours) entièrement constituée de fer. Il a fallu 6 300 tonnes de fer pour construire sa structure à laquelle il faut ajouter près de 1 000 tonnes de fer supplémentaire composé de rivets ainsi que d’autres accessoires.

Le fer nécessaire pour sa construction provenait de gisements ferrifères exploités dans des mines de l’Est de la France. Du minerai de fer, présent dans le sous-sol de cette région, fut extrait et transformé par des procédés sidérurgiques.

Au travers de cette cache, nous vous proposons de découvrir l’origine « proche » et très lointaine de ce métal.

*Si le Champ-de-Mars appartient bien à Arnokovic, la Tour Eiffel, en revanche, appartient à Loulousoleil !

The Eiffel Tower is an iconic monument of Paris. It was built for the Exposition Universelle (international exposition) of 1889 under the direction of Gustave Eiffel, engineer and industrialist.

The Eiffel Tower is an iconic monument of Paris. It was built for the Exposition Universelle (international exposition) of 1889 under the direction of Gustave Eiffel, engineer and industrialist.

It is a tower initially 301 meters high (330 nowadays) made entirely of iron. It took 6,300 tons of iron to build its structure, to which must be added nearly 1,000 tons of additional iron consisting of rivets and other accessories.

The iron needed for its construction came from iron deposits exploited in mines in eastern France. Iron ore, present in the subsoil of this region, was extracted and transformed by iron and steel processes.

Through this cache, we propose you to discover the "close" and very distant origin of this metal.

*If Champ-de-Mars belongs to Arnokovic, the Eiffel Tower, on the other hand, belongs to Loulousoleil! Joke for Arnokovic who is the lucky owner of 7 caches around Champ-de-Mars.

Quelques concepts - Few concepts

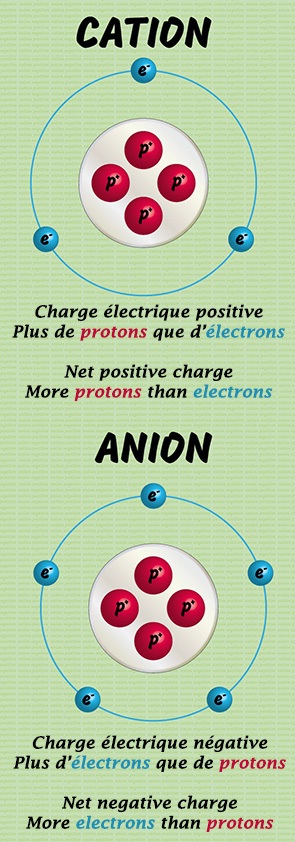

Ion, anion et cation

Ion, anion et cation

Dans un atome neutre, le nombre de protons = le nombre d'électrons. Un ion est un atome, ou un groupe d'atomes, ayant perdu ou gagné un ou plusieurs électrons.

Un anion est un atome (ou une molécule) qui a gagné un ou plusieurs électrons. Comme l'électron est chargé négativement, l'anion porte une charge négative. Il s’agit donc d’un ion négatif.

À l'inverse, un cation est un atome (ou une molécule) qui a perdu un ou plusieurs électrons. La charge électrique globale du cation est donc positive. Il s’agit donc d’un ion positif.

Les ions sont notés en tenant compte de la différence entre le nombre de protons et le nombre d'électrons. Dans la version « simple », on écrira Xn+ et Xn- pour respectivement, un ion qui porte une charge positive (cation) car plus de protons que d’électrons et un ion qui porte une charge négative (anion) car moins de protons que d’électron. Ex : Na+ ou OH- (on n’écrit pas n=1).

Ion, anion and cation

Ion, anion and cation

In a neutral atom, the number of protons = the number of electrons. An ion is an atom, or a group of atoms, that has lost or gained one or more electrons.

An anion is an atom (or a molecule) that has gained one or more electrons. As the electron is negatively charged, the anion has a negative charge. It is therefore a negative ion.

Conversely, a cation is an atom (or molecule) that has lost one or more electrons. The overall electrical charge of the cation is therefore positive. It is therefore a positive ion.

Ions are noted by taking into account the difference between the number of protons and the number of electrons. In the "basic" version, we write Xn+ and Xn- for respectively, an ion that carries a positive charge (cation) because it has more protons than electrons and an ion that carries a negative charge (anion) because it has less protons than electrons. Ex : Na+ or OH- (we do not write n=1).

- - -

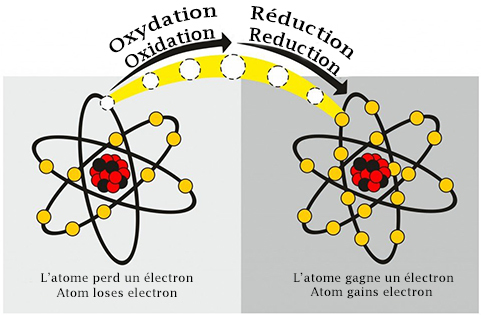

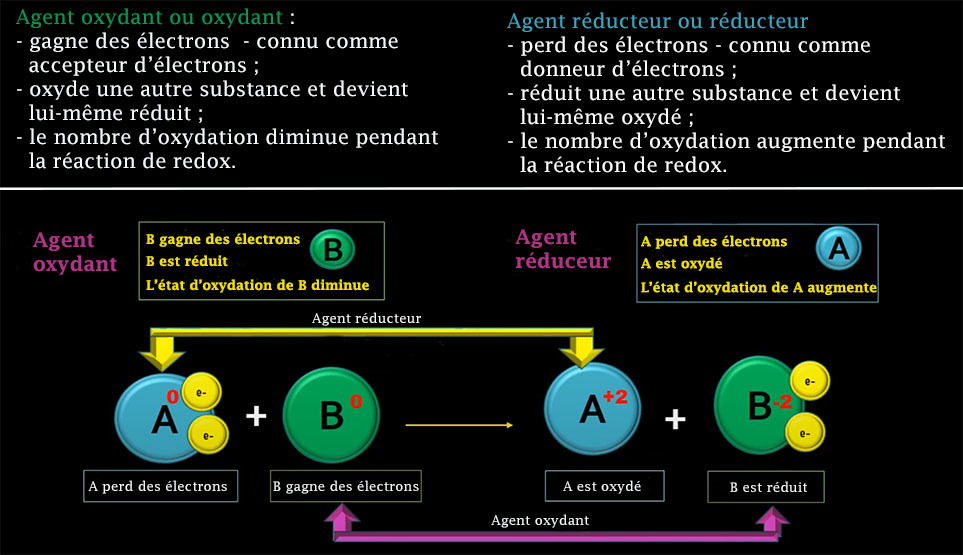

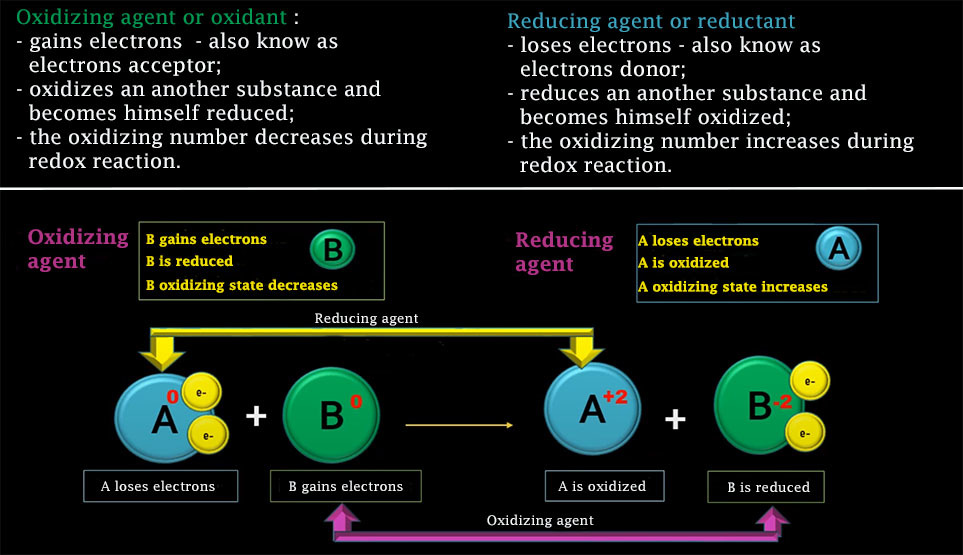

Oxydation, réduction, nombre d’oxydation, oxydant, réducteur et … patati et patata !

Oxydation, réduction, nombre d’oxydation, oxydant, réducteur et … patati et patata !

L'oxydation est un phénomène courant ; une pomme brunie ou un clou rouillé sont deux exemples courants de réactions d'oxydation. L'oxydation ne signifie pas qu'un atome d'oxygène est ajouté au composé. Il s'agit plutôt d'une réaction chimique qui implique la perte d'électrons.

L'oxydation est un phénomène courant ; une pomme brunie ou un clou rouillé sont deux exemples courants de réactions d'oxydation. L'oxydation ne signifie pas qu'un atome d'oxygène est ajouté au composé. Il s'agit plutôt d'une réaction chimique qui implique la perte d'électrons.

Cet électron perdu ne se promène pas sans but dans l'univers ; il est pris en charge par un autre atome. Lorsqu'un atome accepte un électron, il s'agit d'une réaction de réduction. L'oxydation et la réduction vont de pair et sont appelées conjointement des réactions d'oxydoréduction (souvent appelées redox).

Le nombre d'oxydation, également appelé état d'oxydation, est le nombre total d'électrons qu'un atome gagne ou perd afin de former une liaison chimique avec un autre atome.

Les atomes neutres isolés (corps à l’état élémentaire) ont par définition un nombre d’oxydation nul. Si un atome donne (perd) un électron, on dit qu'il a un nombre d'oxydation (n.o.) égal à un +I ; s'il en donne deux, n.o. = +II, etc. Réciproquement, si un atome accepte (reçoit) un électron, son nombre d'oxydation devient -I ; s'il en accepte deux, n.o. = −II, etc.

Le nombre d’oxydation maximal est +VII et le nombre minimal est –II.

Un oxydant, ou agent oxydant ou agent d'oxydation, est un corps simple, un composé ou un ion qui reçoit au moins un électron d'une autre espèce chimique lors d'une réaction d'oxydoréduction. L'oxydant ayant accepté au moins un électron au cours de cette réaction est dit réduit, tandis que l'espèce chimique qui a cédé au moins un électron est dite oxydée. Un oxydant est généralement proche de son état d'oxydation le plus élevé et se comporte par conséquent comme un accepteur d'électron.

Un réducteur est un corps simple, un composé ou un ion qui cède au moins un électron à une autre espèce chimique lors d'une réaction d'oxydoréduction. Le réducteur ayant perdu au moins un électron au cours de cette réaction est dit oxydé, tandis que l'espèce chimique qui a reçu au moins un électron est dite réduite. Un réducteur est généralement proche de son état d'oxydation le plus faible et se comporte par conséquent comme un donneur d'électron.

Les métaux sont généralement considérés comme des éléments qui peuvent facilement perdre des électrons, ils sont donc connus pour être facilement oxydés.

Oxidation, reduction, oxidation number, oxidant, reductant and do on and so forth

Oxidation, reduction, oxidation number, oxidant, reductant and do on and so forth

Oxidation is a common phenomenon; a browned apple or a rusty nail are both common examples of oxidation reactions. Oxidation does not mean that an oxygen atom is added to the compound. Instead, it is a chemical reaction that involves the loss of electrons.

This lost electron does not wander around in the universe aimlessly; it is taken up by another atom. When one atom accepts an electron, it is called a reduction reaction. Oxidation and reduction go hand-in-hand and are jointly referred to as redox reactions.

The oxidation number, also called the oxidation state, is the total number of electrons that an atom gains or loses in order to form a chemical bond with another atom.

Isolated neutral atoms (elementary material) have by definition an oxidation number of zero. If an atom gives (loses) one electron, it is said to have an oxidation number ( o.n.) equal to +I; if it gives two, o.n. = +II, etc. Reversely, if an atom accepts (receives) an electron, its oxidation number becomes -I; if it accepts two, n.o. = -II, etc.

The maximum oxidation number is +VII and the minimum is -II.

An oxidizing agent, or oxidant, is a simple body, compound or ion that receives at least one electron from another chemical species during a redox reaction. The oxidant agent that has accepted at least one electron during this reaction is said to be reduced, while the chemical species that has given up at least one electron is said to be oxidized. An oxidant agnet is usually close to its highest oxidation state and therefore behaves as an electron acceptor.

A reducing agent, or reductant, is a simple body, compound or ion that gives up at least one electron to another chemical species in a redox reaction. The reductant that has lost at least one electron during this reaction is said to be oxidized, while the chemical species that has received at least one electron is said to be reduced. A reducing agent is generally close to its weakest oxidation state and therefore behaves like an electron donor.

Metals are generally considered to be elements that can easily lose electrons, so they are known to be easily oxidized.

- - -

Le fer

Le fer

Le fer, un métal de symbole chimique Fe, est l’un des éléments les plus abondants de la croûte terrestre. Il existe sous plusieurs formes de degré d'oxydation allant de -II à +VII ; cependant, il est principalement présent sous forme +II ou +III.

Le fer, à l’état naturel, existe donc sous deux formes oxydées :

- l’oxyde de fer(II) appelé aussi « fer ferreux », noté Fe(II) mais aussi Fe2+ pour l’ion ferreux. Il est souvent présent sous forme soluble (comme le sucre ou le sel dans l’eau) dans les roches et l’acidité de la roche favorise sa solubilité.

- l’oxyde de fer(III) appelé aussi « fer ferrique » ; noté Fe(III) mais aussi Fe3+pour l’ion ferrique. Il est très rarement présent sous forme soluble dans les roches.

Fe(II) et Fe(III) n'existent pas seuls, mais au sein d'une molécule : Fe3O4, Fe2CO3, FeS2 ...

On peut aussi le trouver sous forme métallique - Fe(0) - qui est le résultat d’un fer transformé par les activités humaines à partir de minerais de fer.

Iron

Iron

Iron, chemical symbol Fe, is one of the most abundant elements in the earth's crust. It exists in several forms of oxidation degree going from -II to +VII; however, it is mainly present in the +II or +III form.

Iron, in its natural state, exists in two oxidized forms:

- iron(II) oxide also called "ferrous iron", noted Fe(II) but also Fe2+ for ferrous ion. It is often present in soluble form (like sugar or salt in water) in rocks and the acidity of the rock favors its solubility.

- Iron(III) oxide also called "ferric iron"; noted Fe(III) but also Fe3+ for ferric ion. It is very rarely found in soluble form in rocks.

Fe(II) and Fe(III) do not exist alone, but within a molecule: Fe3O4, Fe2CO3, FeS2 ...

It can also be found in metallic form - Fe(0) – which is the result of iron transformed by human activities from iron ores.

- - -

Roches

Roches

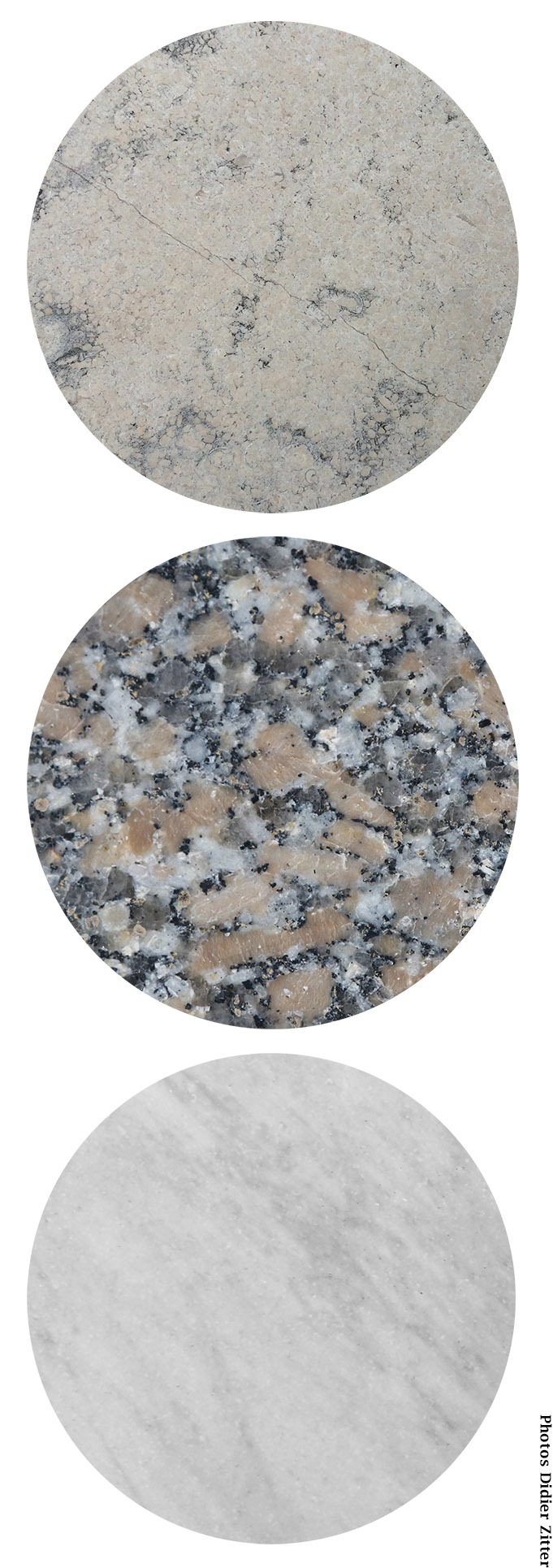

Trois types de roches forment principalement l’écorce terrestre : les roches sédimentaires constituées de sédiments meubles qui se sont transformés (consolidés) au cours de l’évolution géologique ; les roches ignées (ou magmatiques) qui résultent de la solidification du magma, roche fondue sous l'action de la chaleur et de la pression dans les couches profondes de l'écorce terrestre ou dans la couche supérieure du manteau ; les roches métamorphiques issues d’une une transformation à l'état solide de roches sédimentaires, ignées ou… métamorphiques et provoquée par une modification de pression, de température…

Trois types de roches forment principalement l’écorce terrestre : les roches sédimentaires constituées de sédiments meubles qui se sont transformés (consolidés) au cours de l’évolution géologique ; les roches ignées (ou magmatiques) qui résultent de la solidification du magma, roche fondue sous l'action de la chaleur et de la pression dans les couches profondes de l'écorce terrestre ou dans la couche supérieure du manteau ; les roches métamorphiques issues d’une une transformation à l'état solide de roches sédimentaires, ignées ou… métamorphiques et provoquée par une modification de pression, de température…

Rocks

Rocks

There are three main types of rocks which constitute the earth's crust: sedimentary rocks made up of loose unconsolidated sediment that have been transformed into rock during geological history; igneous (or magmatic) rocks, the product of the solidification of magma, which is molten rock generated by partial melting caused by heat and pressure in the deeper part of the Earth's crust or in the upper mantle; metamorphic rocks resulting from a transformation to a solid state of sedimentary, igneous or... metamorphic rocks and caused by a change of pressure, temperature...

- - -

Minerai de fer

Minerai de fer

Le minerai de fer est une roche contenant du fer sous forme de carbonates, d’oxydes, de silicates ou encore de sulfures. Les minerais de fer ont une teneur en fer variable selon le minéral ferrifère : 50 à 67 % pour la magnétite (oxyde), 30 à 67 % pour l’hématite (oxyde), 25 à 45 % pour la limonite (hydroxyde) ou encore 30 à 40 % pour la sidérite (carbonate). Certains minerais ferrifères ne sont pas adaptés à la production de fer : les sulfures (pyrite) ou les silicates. C’est principalement l’hématite qui est à l’origine de la production actuelle du fer.

Le minerai de fer est une roche contenant du fer sous forme de carbonates, d’oxydes, de silicates ou encore de sulfures. Les minerais de fer ont une teneur en fer variable selon le minéral ferrifère : 50 à 67 % pour la magnétite (oxyde), 30 à 67 % pour l’hématite (oxyde), 25 à 45 % pour la limonite (hydroxyde) ou encore 30 à 40 % pour la sidérite (carbonate). Certains minerais ferrifères ne sont pas adaptés à la production de fer : les sulfures (pyrite) ou les silicates. C’est principalement l’hématite qui est à l’origine de la production actuelle du fer.

Iron ore

Iron ore

Iron ore is a rock containing iron in the form of carbonates, oxides, silicates or sulfides. Iron ores have a variable iron content depending on the iron mineral: 50 to 67% for magnetite (oxide), 30 to 67% for hematite (oxide), 25 to 45% for limonite (hydroxide) or 30 to 40% for siderite (carbonate). Some iron ores are not suitable for iron production: sulphides (pyrite) or silicates. It is mainly hematite which is at the origin of the current production of iron.

- - -

Oui, mais d’où provient le minerai de fer ? -> Le fer rubané

Oui, mais d’où provient le minerai de fer ? -> Le fer rubané

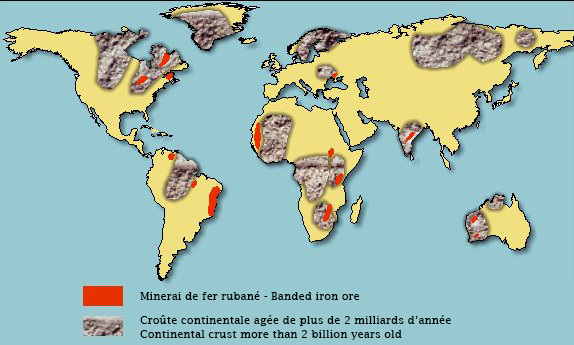

La grande majorité des minerais de fer est constituée par ce qu’on appelle des fers rubanés (banded iron formation ou BIF en anglais). Ces fers rubanés existent sous différents faciès (aspects), mais le faciès classique est constitué de lits de silice et d’hématite (Fe2O3, oxyde ferrique où le fer est sous sa forme oxydée Fe3+). Il s’agit toujours de formations sédimentaires marines. Leur âge est essentiellement archéen (période géologique allant de -4 000 millions à -2 500 millions d’années) ou paléoprotérozoïque (période géologique de -2 500 Ma à -1 600 Ma).

Les fers rubanés de l’Archéen, dont les plus vieux sont âgés de -3.8 Ga, forment des petits dépôts discontinus au sein des sédiments. Les fers rubanés du Paléoprotozoïque datent de -2.5 à -1.9 Ga et forment de très gros gisements. Il s’agit de dépôts répartis sur de vastes surfaces et constituent la majorité des gisements d’importance économique.

Yes, but where does the iron ore come from? -> Banded iron

Yes, but where does the iron ore come from? -> Banded iron

The great majority of iron ores are made up of what is called banded iron formation (BIF). These BIF exist under different facies (aspects), but the classical facies is constituted by silica and hematite (Fe2O3, ferric oxide where iron is in its oxidized form Fe3+). They are always marine sedimentary formations. Their age is essentially Archean (geological period from 4,000 million years ago to 2,500 million years ago) or Paleoproterozoic (geological period from 2,500 mya to 1,600 mya).

The great majority of iron ores are made up of what is called banded iron formation (BIF). These BIF exist under different facies (aspects), but the classical facies is constituted by silica and hematite (Fe2O3, ferric oxide where iron is in its oxidized form Fe3+). They are always marine sedimentary formations. Their age is essentially Archean (geological period from 4,000 million years ago to 2,500 million years ago) or Paleoproterozoic (geological period from 2,500 mya to 1,600 mya).

The Archean banded irons, the oldest of which are 3,800 million years old, form small discontinuous deposits within the sediments. The Paleoprotozoic banded irons date from 2,500 to 1,900 mya and form very large deposits. These deposits are distributed over large areas and constitute the majority of deposits of economic importance.

- - -

Oui, mais d’où proviennent les dépôts ? -> L’oxydation de Fe2+ en Fe3+

Oui, mais d’où proviennent les dépôts ? -> L’oxydation de Fe2+ en Fe3+

Le fer ferreux Fe(II) ou l’ion ferreux Fe2+ sont solubles dans l’eau. Le fer ferrique Fe(III) ou l’ion ferrique Fe3+ sont insolubles dans l’eau (sauf si l'eau est très acide).

Puisque du Fe3+ (insoluble) marin a précipité à l'Archéen, c'est que l'eau de mer de cette époque contenait du fer en solution, forcément sous sa forme soluble Fe2+. Ce qui fait penser que la mer ou l’océan de cette époque était réduite (cf les définitions) comme l’était sans doute l’atmosphère sus-jacente. Si de l'hématite (Fe3+) a précipité localement, mais dans de nombreuses régions du monde entre -3,8 et -2,5 Ga, c'est que l'eau de mer habituellement réduite est localement devenue oxydante, ce qui a entraîné l'oxydation des ions Fe2+ en ions Fe3+ et donc leur précipitation (sous forme d'hématite).

Quant aux gisements du Protérozoïque inférieur (les plus abondants) datant de -2,5 à –1,9 Ga, ils seraient dus à l'oxydation générale de l'eau de mer par l'atmosphère devenant elle-même riche en O2 (dioxygène) à cette époque.

Yes, but where do the deposits come from? ->Oxidation of Fe2+ to Fe3+

Yes, but where do the deposits come from? ->Oxidation of Fe2+ to Fe3+

The ferrous iron Fe(II) or the ferrous ion Fe2+ are soluble in water. The ferric iron Fe(III) or the ferric ion Fe3+ are insoluble in water (unless water is highly acidic).

As marine Fe3+ (insoluble) precipitated in the Archaean, it means that the sea water of that time contained iron in solution, necessarily in its soluble form Fe2+. This makes us think that the sea or the ocean of this period was reduced (cf. definitions) as was probably the overlying atmosphere. If hematite (Fe3+) precipitated locally, but in many parts of the world between -3.8 and -2.5 bya, it is because the usually reduced sea water became locally oxidizing, which led to the oxidation of Fe2+ ions into Fe3+ ions and thus their precipitation (in the form of hematite).

Concerning the Paleoproterozoic deposits (the most abundant) dating from -2.5 to -1.9 bya, would be due to the general oxidation of seawater by the atmosphere, which itself became rich in O2 (oxygen) at that time.

- - -

Oui, mais d’où provient le fer sous sa forme soluble ? -> L’hydrothermalisme et érosion

Oui, mais d’où provient le fer sous sa forme soluble ? -> L’hydrothermalisme et érosion

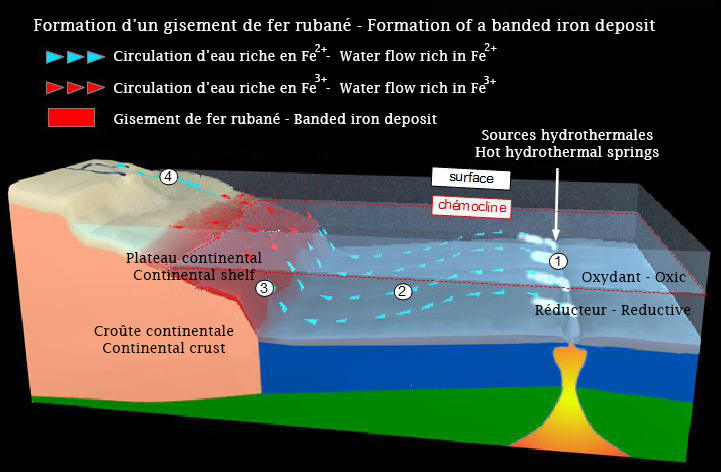

Dans la nature actuelle, l’essentiel du fer des océans provient des fleuves et des poussières arrachées aux continents après un mécanisme d’altération de la roche. Cependant à l’Archéen et au Paléoprotozoïque son origine était différente. Au Paléoprotozoïque, le fer était produit au niveau des sources hydrothermales (1). À l’état réduit (Fe2+), il était soluble dans les eaux réductrices et circulait grâce aux courants profonds (2). Des remontées d’eau (upwellings) le faisaient remonter vers la surface (3). Il traversait une ligne chimique (la chémocline) séparant les eaux réductrices profondes des eaux oxydantes de surface. Il s'oxydait alors à l'état de Fe3+ et précipitait sous forme d'hématite qui sédimentait sur le fond au niveau du plateau continental. Un faible part du fer du gisement venait de l'érosion des continents (4).

Dans la nature actuelle, l’essentiel du fer des océans provient des fleuves et des poussières arrachées aux continents après un mécanisme d’altération de la roche. Cependant à l’Archéen et au Paléoprotozoïque son origine était différente. Au Paléoprotozoïque, le fer était produit au niveau des sources hydrothermales (1). À l’état réduit (Fe2+), il était soluble dans les eaux réductrices et circulait grâce aux courants profonds (2). Des remontées d’eau (upwellings) le faisaient remonter vers la surface (3). Il traversait une ligne chimique (la chémocline) séparant les eaux réductrices profondes des eaux oxydantes de surface. Il s'oxydait alors à l'état de Fe3+ et précipitait sous forme d'hématite qui sédimentait sur le fond au niveau du plateau continental. Un faible part du fer du gisement venait de l'érosion des continents (4).

Yes, but where does the iron in its soluble form come from? -> Hydrothermalism and erosion

Yes, but where does the iron in its soluble form come from? -> Hydrothermalism and erosion

In today's nature, most of the iron in the oceans comes from rivers and dust taken from the continents after an weathering mechanism of the rock. However, in the Archean and Paleoprotozoic ages its origin was different. In the Paleoprotozoic, iron was produced at hydrothermal springs (1). In its reduced state (Fe2+), it was soluble in reducing waters and circulated thanks to deep currents (2). Upwellings brought it to the surface (3). It crossed a chemical line (the chemocline) separating the deep reducing waters from the oxidizing surface waters. It was then oxidized to Fe3+ and precipitated as hematite that was deposited on the bottom of the continental shelf. A small part of the iron in the deposit came from the erosion of the continents (4).

- - -

Ah oui, et pourquoi le milieu (air/eau) est-il devenue oxydant ? -> Les cyanobactéries

Ah oui, et pourquoi le milieu (air/eau) est-il devenue oxydant ? -> Les cyanobactéries

Les cyanobactéries sont des organismes microscopiques procaryotes. Leur cytoplasme contient notamment des pigments chlorophylliens.

Les premiers producteurs de dioxygène (O2) sont probablement des procaryotes, proches des cyanobactéries actuelles, qui édifiaient des constructions calcaires : les stromatolites dont les plus anciens sont datés autour de -3,5 Ga. Ces cyanobactéries consomment du CO2 et libèrent du dioxygène par photosynthèse. On peut donc estimer que c’est l’apparition de la photosynthèse aquatique qui a permis l’apparition du dioxygène. Ce dernier a été libéré dans les océans et se trouvait donc à l’état dissout dans un premier temps. C’est ainsi qu’il a oxydé le fer des océans. Une fois le fer totalement oxydé et l’océan saturé en dioxygène, celui-ci a pu diffuser dans l’atmosphère il y a 2.2 milliards d’années.

Oh yes, and why has the environment (air/water) become oxidizing? -> Cyanobacteria

Oh yes, and why has the environment (air/water) become oxidizing? -> Cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria are microscopic prokaryotic organisms. Their cytoplasm contains chlorophyll pigments.

The first producers of oxygen (O2) are probably prokaryotes, close to the present cyanobacteria, which built calcareous constructions : stromatolites, the oldest of which are dated around 3.5 billion years ago. These cyanobacteria consume CO2 and release oxygen by photosynthesis. We can therefore estimate that it is the appearance of aquatic photosynthesis that allowed the appearance of oxygen. Oxygen was released into the oceans and was therefore in a dissolved state at first. This is how it oxidized the iron in the oceans. Once the iron was completely oxidized and the ocean was saturated with oxygen, it could diffuse into the atmosphere 2.2 billion years ago.

- - -

Oui, mais avant ? -> L'accrétion de la planète

Oui, mais avant ? -> L'accrétion de la planète

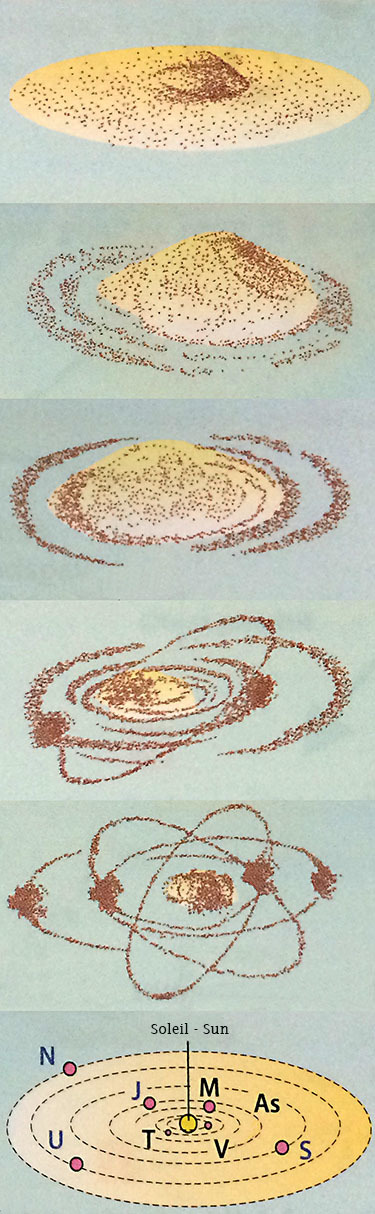

Il y a 4,56 d’années, un nuage de gaz et de poussières appelé « nébuleuse solaire » et animé d’une faible vitesse de rotation s’est contracté sous l’effet de sa propre gravité. À un certain stade de la contraction, la nébuleuse prend forme d’un disque aplati. Dans la zone centrale se forme un noyau qui concentre l’essentiel de la masse du système. Une augmentation de la pression et de la température dans cette région permet aux réactions de fusion nucléaire de démarrer marquant ainsi la naissance du soleil.

Les planètes se sont formées à partir du disque protoplanétaire de gaz et de poussière (98% d’H et d’He et 2% d’éléments lourds : Fe, Al, etc.) en rotation autour du jeune soleil.

Les planètes se sont formées à partir du disque protoplanétaire de gaz et de poussière (98% d’H et d’He et 2% d’éléments lourds : Fe, Al, etc.) en rotation autour du jeune soleil.

En rotation autour du jeune soleil, les grains de poussières se rencontrent et forment de plus gros agrégats ... qui s’agglomèrent jusqu’à former des corps rocheux de taille kilométrique appelés planétésimaux. La rencontre entre planétésimaux permet de former des objets encore plus gros qui attirent encore plus de matière en raison de l’augmentation de leur force de gravitation : c’est l’emballement de l’accrétion. Au hasard des rencontres et de la force de gravité, des objets plus gros se forment : les proto-planètes. Le phénomène d’accrétion dégage une grande quantité de chaleur qui fait fondre la roche. À cela s’ajoute la chaleur dégagée par la désintégration des éléments radioactifs. Lors de la fusion, les matériaux les plus lourds dominés par le fer vont se concentrer vers le centre de l’objet pour former un noyau métallique, tandis que le plus légers vont rester en surface formant une croûte. Entre les deux couches demeurent les éléments intermédiaires qui forment le manteau silicaté riche en fer…

Yes, but before? -> Planet accretion

Yes, but before? -> Planet accretion

4.56 billion years ago, a cloud of gas and dust called "solar nebula" and animated by a low speed of rotation contracted under the effect of its own gravity. At a certain point of the contraction, the nebula takes the form of a flattened disk. In the central region a core is formed which concentrates most of the mass of the system. An increase in pressure and temperature in this region allows nuclear fusion reactions to start, marking the birth of the sun.

The planets were formed from the protoplanetary disk of gas and dust (98% H and He and 2% heavy elements: Fe, Al, etc.) in rotation around the young sun.

In rotation around the young sun, the dust grains meet and form larger aggregates ... which agglomerate to form rocky bodies of kilometer size called planetesimals. The meeting between planetesimals allows to form even bigger objects which attract even more matter because of the increase of their gravitational force: it is the runaway accretion. By chance of meetings and the force of gravity, larger objects are formed: the proto-planets. The phenomenon of accretion releases a large amount of heat that melts the rock. In addition, the heat released by the decay of radioactive elements. During the fusion, the heaviest materials mainly iron will concentrate towards the center of the object to form a metallic core, while the lightest will remain on the surface forming a crust. Between the two layers remains the intermediate elements which form the silicate mantle rich in iron...

- - -

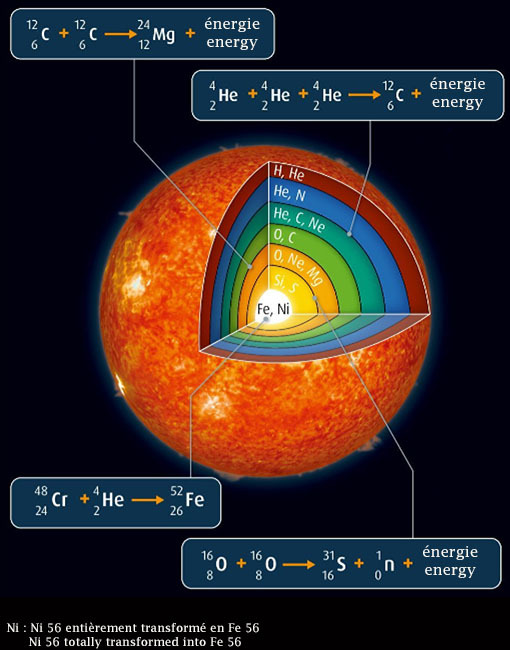

Oui, mais encore avant ? -> La nucléosynthèse stellaire

Oui, mais encore avant ? -> La nucléosynthèse stellaire

Dans le domaine de l'astrophysique, la nucléosynthèse stellaire est le terme qui désigne l'ensemble des réactions de fusion nucléaire qui ont lieu à l'intérieur des étoiles et dont le résultat est la production de la plupart des noyaux atomiques. On distingue la nucléosynthèse calme au travers de laquelle sont produits tous les éléments jusqu’au fer (Fe) et la nucléosynthèse explosive (explosion de l’étoile) au travers de la laquelle sont produits tous les éléments jusqu’à l’uranium (U). En raison de la « petite » taille (masse plus exactement) de « notre » soleil, il n’est pas en mesure de produire autre chose que de l’hélium, du carbone et de l’oxygène (He actuellement puis C et O en fin de vie). Le fer présent sur terre a donc été produit avant la formation de « notre » soleil par une étoile plus massive.

Dans le domaine de l'astrophysique, la nucléosynthèse stellaire est le terme qui désigne l'ensemble des réactions de fusion nucléaire qui ont lieu à l'intérieur des étoiles et dont le résultat est la production de la plupart des noyaux atomiques. On distingue la nucléosynthèse calme au travers de laquelle sont produits tous les éléments jusqu’au fer (Fe) et la nucléosynthèse explosive (explosion de l’étoile) au travers de la laquelle sont produits tous les éléments jusqu’à l’uranium (U). En raison de la « petite » taille (masse plus exactement) de « notre » soleil, il n’est pas en mesure de produire autre chose que de l’hélium, du carbone et de l’oxygène (He actuellement puis C et O en fin de vie). Le fer présent sur terre a donc été produit avant la formation de « notre » soleil par une étoile plus massive.

Yes, but even before? -> Stellar nucleosynthesis

Yes, but even before? -> Stellar nucleosynthesis

In the field of astrophysics, stellar nucleosynthesis is the name given to the set of nuclear fusion reactions that take place inside stars and whose result is the production of most atomic nuclei. A difference is made between calm nucleosynthesis, through which all elements up to iron (Fe) are produced, and explosive nucleosynthesis (explosion of the star) through which all elements up to uranium (U) are produced. Because of the "small" size (mass more precisely) of "our" sun, it is not able to produce anything other than helium, carbon and oxygen (He currently and then C and O at the end of life). The iron on earth was therefore produced before the formation of our sun by a more massive star.

- - -

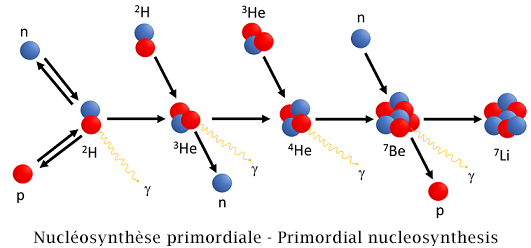

Oui, mais avant avant ? -> La nucléosynthèse primordiale

Oui, mais avant avant ? -> La nucléosynthèse primordiale

La nucléosynthèse primordiale est une théorie d'astrophysique (ici « théorie » ne signifie pas que la nucléosynthèse se situe dans le domaine du probable, mais qu’elle découle d’un ensemble de principes, de règles et de calculs bien établis) qui permet d'expliquer la formations des noyaux atomiques légers : deutérium, hélium, et en parti lithium, béryllium, bore.

Selon ce modèle ou cette théorie, lors des premiers instants de l'univers, grâce à la chaleur de l'ordre du milliard de degrés, des atomes légers se seraient formés par les interactions de particules élémentaires (fermions, bosons).

Yes, but before before ? -> Primordial nucleosynthesis

Yes, but before before ? -> Primordial nucleosynthesis

Primordial nucleosynthesis is a theory of astrophysics (here "theory" does not mean that nucleosynthesis is in the probable domain, but that it follows from a set of principles, rules and well-defined calculations) which allows to explain the formation of light atomic nuclei: deuterium, helium, and partly lithium, beryllium, boron.

Primordial nucleosynthesis is a theory of astrophysics (here "theory" does not mean that nucleosynthesis is in the probable domain, but that it follows from a set of principles, rules and well-defined calculations) which allows to explain the formation of light atomic nuclei: deuterium, helium, and partly lithium, beryllium, boron.

According to this model or theory, during the first times of the universe, due to the heat of the order of a billion degrees, light atoms would have been formed by the interactions of elementary particles (fermions, bosons).

- - -

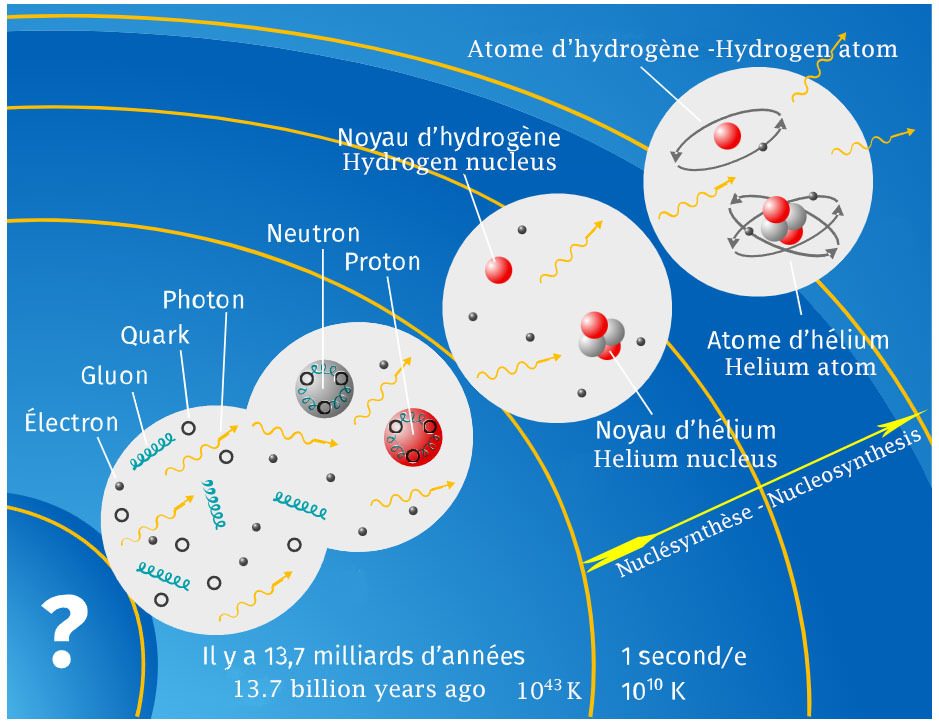

Oui, mais … ? -> Oui, ... mais ta g..... !

Oui, mais … ? -> Oui, ... mais ta g..... !

Avant la nucléosynthèse primordiale, existent plusieurs étapes de transformation de l’univers naissant : ère de Planck, inflation cosmique, préchauffage, re-chauffage, baryogénèse, ère leptonique, … La physique actuelle se heurte au mur de Planck, dont l’instant, appelé temps de Planck, est postérieur de 10-43 seconde après le Big Bang (t=0). Avant cet instant, à l’ère de Planck, les lois actuelles de la physique n’ont plus cours et il est donc impossible de savoir ce qui s’est passé. Seules des hypothèses peuvent être formulées.

Avant la nucléosynthèse primordiale, existent plusieurs étapes de transformation de l’univers naissant : ère de Planck, inflation cosmique, préchauffage, re-chauffage, baryogénèse, ère leptonique, … La physique actuelle se heurte au mur de Planck, dont l’instant, appelé temps de Planck, est postérieur de 10-43 seconde après le Big Bang (t=0). Avant cet instant, à l’ère de Planck, les lois actuelles de la physique n’ont plus cours et il est donc impossible de savoir ce qui s’est passé. Seules des hypothèses peuvent être formulées.

Yes, but ... ? -> Yes, ... but shut up !

Yes, but ... ? -> Yes, ... but shut up !

Before the primordial nucleosynthesis, there are several steps of transformation of the newborn universe: Planck era, cosmic inflation, preheating, reheating, baryogenesis, leptonic era, ... The current physics comes up against the Planck wall, whose instant, called Planck time, is 10-43 seconds later than the Big Bang (t=0). Before this point in time, in the Planck era, the current laws of physics are no longer valid and it is therefore impossible to know what happened. Only hypotheses can be formulated.

- - -

Le fer est partout

Le fer est partout

Hormis le fer sous sa forme métallique comme pour la tour Eiffel ou toute autre construction utilisant le fer (métallique), presque toutes les roches contiennent du fer, le plus souvent sous forme oxydée (Fe3+). La couleur rouge d’une roche ou ses variations (violacé, rose, orangé, ocre, brun, beige, …, ou leur combinaison, mais aussi verdâtre : Fe2+, etc.) indique la présence de fer dans cette roche, mais pas forcément dans les mêmes proportions que dans les roches contenant du minerai de fer. La teneur moyenne en fer de la croûte terrestre se situe aux alentours de 5 %. Le noyau de la terre, est quant à lui composé de fer (allié à du nickel) sous forme solide pour la partie interne et liquide pour la partie externe.

Hormis le fer sous sa forme métallique comme pour la tour Eiffel ou toute autre construction utilisant le fer (métallique), presque toutes les roches contiennent du fer, le plus souvent sous forme oxydée (Fe3+). La couleur rouge d’une roche ou ses variations (violacé, rose, orangé, ocre, brun, beige, …, ou leur combinaison, mais aussi verdâtre : Fe2+, etc.) indique la présence de fer dans cette roche, mais pas forcément dans les mêmes proportions que dans les roches contenant du minerai de fer. La teneur moyenne en fer de la croûte terrestre se situe aux alentours de 5 %. Le noyau de la terre, est quant à lui composé de fer (allié à du nickel) sous forme solide pour la partie interne et liquide pour la partie externe.

Attention, tout (roche, minéral) ce qui est rouge (et ses nuances) n’est pas forcément dû à la présence de fer. Il peut s’agir de la présence de manganèse, de chrome, de mercure, d’uranium, …

Iron is everywhere

Iron is everywhere

Besides iron in its metallic form as in the Eiffel Tower or any other construction using (metallic) iron, almost all rocks contain iron, most often in oxidized form (Fe3+). The red color of a rock or its variations (purplish, pink, orange, ochre, brown, beige, ..., or their combination, but also greenish : Fe2+, etc.) indicates the content of iron in this rock, but not necessarily in the same ratio as in rocks containing iron ore. The average iron content of the earth's crust is around 5%. The core of the earth is composed of iron (allied to nickel) in solid form for the internal part and liquid for the external part.

Note that not everything (rock, mineral) that is red (and its shades) is necessarily due to the presence of iron. It can be the presence of manganese, chromium, mercury, uranium, ...

Références - References

Difference betweeen oxidizing agent and reducing agent

Origine des oxydes ferriques terrestres anciens

Les étapes de la formation de la terre

Origine de la matière

https://www.techno-science.net

Pour valider la cache - Logging requirements

Aux coordonnées indiquées vous observerez les pavés au sol (zone A) en avant-plan comme sur la photo ci-dessous. Puis, vous vous rendrez à la zone B, comme en arrière-plan sur cette photo, et vous observerez cette zone.

Aux coordonnées indiquées vous observerez les pavés au sol (zone A) en avant-plan comme sur la photo ci-dessous. Puis, vous vous rendrez à la zone B, comme en arrière-plan sur cette photo, et vous observerez cette zone.

At the specified coordinates you will see paving stones on the ground (area A) in the foreground as in the picture below. Then you will go to area B, as in the background of this picture, and you will observe this area.

At the specified coordinates you will see paving stones on the ground (area A) in the foreground as in the picture below. Then you will go to area B, as in the background of this picture, and you will observe this area.

Travail à effectuer

Travail à effectuer

- Parmi les pavés au sol, en justifiant votre réponses, quels est/sont celui/ceux, selon vous, qui indique/nt clairement la présence de fer dans sa/leur constitution ? Y décelez-vous du fer sous forme métallique - Fe(0) ?

- Quelle est la particularité du pavé n°4 ?

- En zone B, quel élément est constitué de fer ? Sous quelle forme est-il visible ? Une réaction d’oxydoréduction est elle en cours ? Si oui, quel élément en est responsable ?

- Une photo de vous, ou d’un objet caractéristique vous appartenant, prise dans les environs immédiats (pas de photo « d’archive » svp) est à joindre soit en commentaire, soit avec vos réponses. Conformément aux directives mises à jour par GC HQ et publiées en juin 2019, des photos peuvent être exigées pour la validation d'une earthcache.

Marquez cette cache « Trouvée » et envoyez-nous vos propositions de réponses, en précisant bien le nom de la cache, soit via notre profil, soit via la messagerie geocaching.com (centre de messagerie) et nous vous répondrons en cas de problème. « Trouvée » sans réponses sera supprimée.

- - -

Homework

Homework

- Among the paving stones on the ground, justifying your answer, which one(s), according to you, clearly indicate(s) the presence of iron in its/their make-up? Do you see iron in metallic form - Fe(0) ?

- What is the particular feature of paving stone n°4?

- In area B, which element is made of iron? In what form is it visible? Is a redox reaction taking place? If so, which element is responsible?

- A photo of your, your GPS or something else personal taken in the immediate aera (no "stock" photos please) is to be attached either as a comment or with your answers. In accordance with updated GC HQ guidelines published in June 2019, photos may be required for validation of an earthcache.

Log this cache "Found it", and send us your answers, don't forget to mention the name of the cache, via our profile or via geocaching.com (Message Center) and we will contact you in case of any problemes. "Found it" without the anwers will be deleted.