In 2019, I placed a letterbox in Clermont/Loftridge Park. I was surprised by how many finders commented on the significant erosion of the streams in this Park and hoped FCPA would do something about it. Those comments inspired this Earthcache, where you will learn about the hidden story of stream bank erosion in southeastern Fairfax County. To understand why these streams seem to erode so quickly, you'll need a DeLorean that can hit 88 mph, the skills of an engineering geologist, and the size of Ant Man. Are you ready?

Permission for this cache was generously given by Fairfax County Park Authority. As with all FCPA parks, night caching is not permitted. At Ground Zero, you'll find a pathway down to the stream bed. To get the most of this cache, you may want to get your feet wet or wear water-proof boots, but it can be done while remaining on the path. This cache might be difficult after a heavy rain.

Back in Time

Between 145 and 65 million years ago during the Cretaceous, freshwater streams meandered along the inner margin of the Coastal Plain, depositing layers of sand and clay. These layers outcrop in the stream bed at GZ. A distinctive feature of deposition in flowing water (or wind) is crossbedding. During the formation of cross beds, mineral grains are eroded from the upstream edge of a ripple and deposited on the downstream side. Sets of these cross beds often sit on top of one another.

On top of these layers of sand and clay, the ancestral Potomac River system deposited sands and coarse gravel during the Tertiary period. The boundary between these sand and clay rich layers and the coarser gravel layer is an unconformity, a missing unit of geologic time where erosion took place between periods of deposition. Together, the sand and clay layers and the overlying coarse gravels are called the Potomac Formation. In the millions of years since, these layers were not compacted into their solid rock equivalents - sandstone, shale, and conglomerate - but remained as loose sediment layers.

Question 1: Look carefully at the stream bank. Do you see any cross bedding? Are layers of sand and clay AND the coarse gravels present in the stream bank?

An Engineering Geologist?

When you drive through a roadcut, have you ever wondered who decided how steep to make the sides of the cut? The answer is an engineering geologist, someone who understands how geology plays into construction projects, including controlling stream bank erosion. The U.S. Geological Survey published an entire book on engineering geology in the Potomac Formation, with an accompanying map that identified GZ as the Potomac Formation.

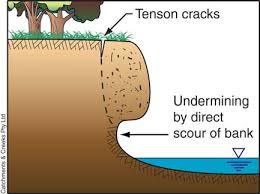

Most people think of stream bank erosion happening as the result of undercutting. Water erodes the bottom of a steep stream bank and, unsupported from below, the overlying soil collapses into the stream.

O

O

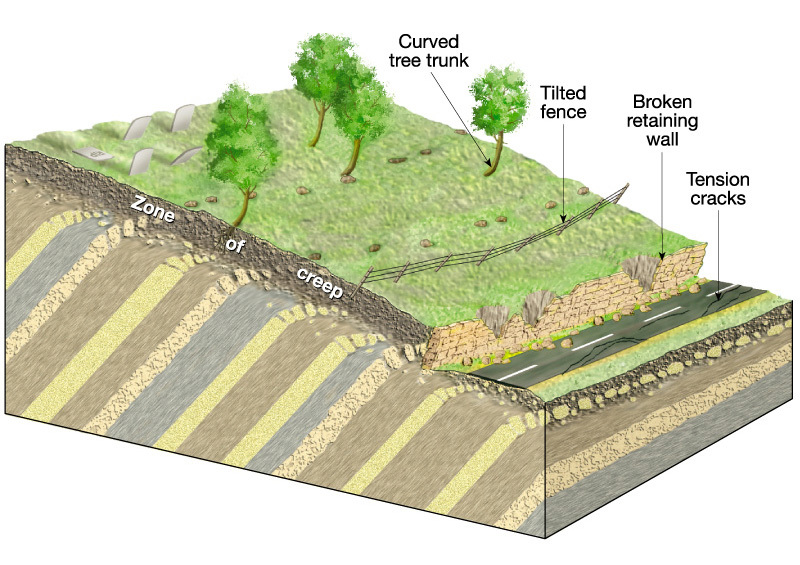

The USGS publication identified that the Potomac Formation is also subject to creep and slumping. During creep, soil moves slowly downhill. This often causes failure of man-made structures like fences, retaining walls, buildings, or roads. An interesting indicator of creep in the woods are bent trees. As the soil creeps downhill rotating the base of the tree, the tree top continues to grow upwards towards the sun, producing a bent tree.

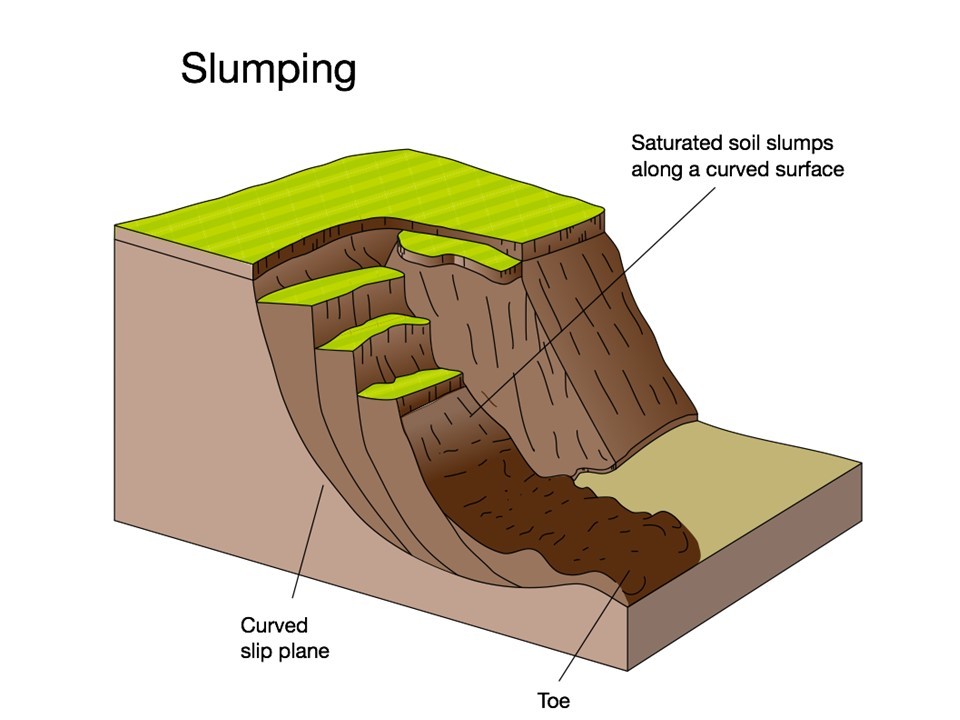

In slumping, the hillside collapses along a series of curved slip planes. Often times, this results in collapse well beyond the boundaries of the stream and formation of a series of stepped terraces.

Question 2: Do you see any evidence of slope creep or slumping at GZ? What are they? [Optional: Look at the hillside at Stage 2]

Question 3: If this area wasn't a Fairfax County Park, would you build houses on the hillside above the creek? Why or why not?

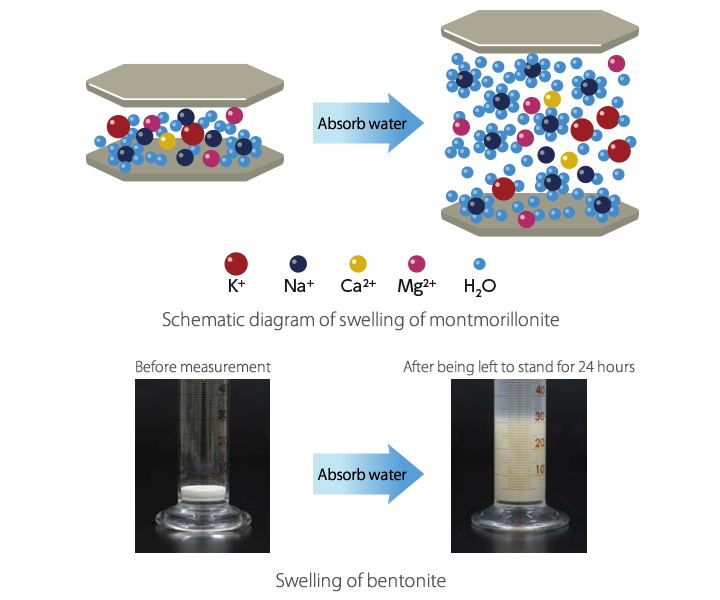

The Little Mineral

In southeastern Fairfax County, the Potomac Formation contains a tiny clay mineral called montmorillonite. How tiny? A single crystal is 1/100,000th the width of a human hair. Montmorillonite, sometimes called by the commercial name bentonite, strikes fear into the hearts of engineering geologists everywhere! Montmorillonite is what geologists call a layer lattice silicate. Between sheets of silica and aluminum (grey in the picture), montmorillonite can absorb water - lots of water. As the picture shows, exposing it to water causes it to swell to six times its original volume! The swelling of montmorillonite can break the unconsolidated sand and clay layers apart, causing the stream bank to collapse. So, while controlling stream flow is a good thing to do, this tiny mineral - incorporated into the layers in the stream bank more than 65 million years ago - is one of the main reasons erosion is so severe here in southeastern Fairfax County.

So, how can you tell if montmorillonite is present? Geologists use X-ray diffraction to determine if montmorillonite is the clay present, but you can determine whether the stream bank here is richer in sand or montmorillonite-rich clay! There are three ways to do this. First, sand tends to be brown to red in color, while clay is brown or, commonly, gray. Second, you can rub a bit between your fingers - sand will feel more gritty and clay smooth. Geologists have a third way - they chew it. Put a tiny bit between your teeth. If it's gritty, it's sand, but if it's smooth, you have clay. Several years ago at GeoWoodstock, a panelist on Earthcaches described Earthcache reviewers as "weird people who like to lick rocks." Heck, geologists do more than lick them, we chew them!

Question 4: Do you think the streambank here has more clay or sand? Why? What method did you use to reach this conclusion?

Logging Requirements

After reading the information above, send answers to questions 1-4 to the cache owner:

Question 1: Look carefully at the stream bank. Do you see any cross bedding? Are layers of sand and clay AND the coarse gravels present in the stream bank?

Question 2: Do you see any evidence of slope creep or slumping at GZ? What are they? [Optional: Look at the hillside at Stage 2]

Question 3: If this area wasn't a Fairfax County Park, would you build houses on the hillside above the creek? Why or why not?

Question 4: Do you think the streambank here has more clay or sand? Why? What method did you use to reach this conclusion?

WITH YOUR LOG, POST A PHOTO. Posting a photo that readily indicates that you (and anyone else logging the find) were at the location. You do not have to show your face, but the photo should include you or a personal item. Please do not show any answers to any of the questions above. NOTE: Per newly published Earthcache regulations, this is required to claim the find.

If responses to the questions above are not received in a reasonable time period, cachers will receive a request for answers. Failure to respond may result in deletion of your log.

REFERENCE

Obermeier S.F. (1984) Engineering geology and design of slopes for Cretaceous Potomac deposits in Fairfax County, Virginia, and vicinity. Geological Survey Bulletin 1556.

Best Earthcache