The description is in both Czech and English, Popis je jak v češtině tak v angličtině.

ZDE JSOU POZNATKY NA CO SE U KEŠE PŘIPRAVIT/HERE ARE THINGS ON WHAT TO PREPARE FOR AT THE GEOCACHE:

1.) Keš je záměrně na odporném místě - Proč? = Jelikož jsem chtěl využít ohavných prostorů Libně a Palmovky a také téma této keše musí odpovídat prostředí, kačer se musí vcítit do krysi, myši či potkana.

2.) Jsem si vědom, že v pravidlech stojí, že by keš měla být na pěkném místě, ALE to by pak nedával smysl tento název - přece keš o pastích na krysi nemůže být v uklizené čtvrti či v čistém prostoru.

3.) Ano, připravte se na to, že je tu trochu binec, ale právě proto sem keš zapadá :)

4.) Oceňuji citaci od ToBeJa: "Tohle je nejhnusnější keška na nejhnusnějším místě, ale dobrá schovka." - celkem to dává smysl s překvapením, které keš nabízí. XD

5.) Nejvíce mě pobavil komentář, jež hodně prozrazuje způsob uložení keše od Potsii: "No fuj! Sáhla jsem na to a málem jsem zařvala! Ale nakonec jsem se pochechtávala až domů, dík za nápaditou keš!"

-------------------------

1.) The cache is deliberately in a nasty place - Why? = Because I wanted to take advantage of the hideous spaces of Libeň and Palmovka and the theme of this cache must correspond to the environment, the duck must empathize with a rat, mouse or rat.

2.) I'm aware that the rules say that the cache should be in a nice place, BUT then the title wouldn't make sense - after all, a cache about rat traps can't be in a tidy neighborhood or clean area.

3.) Yes, be prepared for it to be a bit messy, but that's why the cache fits in :)

4.) Appreciate the quote from ToBeJa: "This is the ugliest cache in the ugliest place, but a good hiding place" - it makes total sense with the surprise the cache offers. XD

5.) I was most amused by the comment that reveals a lot about the way the cache was saved by Potsii: "Ugh! I touched it and almost screamed! But I ended up giggling all the way home, thanks for the imaginative cache!"

ÚVOD K PASTÍM NA MYŠI, KRYSI A JINOU HAVĚŤ/AN INTRODUCTION TO MOUSE, RAT AND OTHER VERSATILE TRAPS:

Historie pastí na myši není (dosud) zavedeným předmětem výzkumu v historii hmotné kultury.

Tato nevědomost umožnila Michaelovi Beheovi (1996) tvrdit o všudypřítomné ploché pasti jako příkladu systému, který se zdánlivě nemohl vyvinout. Tyto pasti nemohou chytit myši s chybějící částí.

Z tohoto prostého faktu, který se nazývá neredukovatelná složitost, Behe vyvodil závěr trojskoku: 1.) neredukovatelně složité systémy nemohou mít žádného pracovního předchůdce s jednou částí menší; 2.) proto nemohou mít nepřetržitou historii; 3.) proto se nemohou vyvíjet.

Tato protidarwinovská výzva přináší bližší pohled na historii pastí myší, která se týká zejména studia hmotné kultury.

Část I. (Vyvrácení Beheho trojskokových závěrů) tohoto příspěvku dokazuje, že Beheovy závěry jsou v každém kroku špatné: 1.) Klíčový předchůdce současných plochých pastí měl o jednu část méně. 2.) Historie pastí na myši je nepřetržitá a velmi stará. 3.) Všechny předpoklady pro vývoj se vyskytují v populacích pastí na myši.

Část II (Evoluce hmotné kultury) představuje základ pro případovou studii o změně hmotné kultury. Tato diskuse je v současné době v plném proudu týkající se evoluční archeologie (např. O’Brien a Lyman 2004; Gabora 2006). Zde mohou pasti na myši zakrýt mezeru mezi artefakty, které jsou vyrobeny pouze z jedné části (např. Kamenné nástroje), a vysoce sofistikovanými stroji s velkým počtem dílů (např. Parní stroje, auta a počítače) a mohou překlenout doba od doby bronzové po současnost. Nakonec část I ilustruje, proč jsou všechny Beheho závěry falešné, a část II, proč je možné volně diskutovat o výhodách a nevýhodách evoluce hmotné kultury, aniž by se cítili přitlačeni k jedné straně kreacionistickými tvrzeními. Na začátku je však zapotřebí koncepční rámec. Koncepční rámec Výroba artefaktů je obdobou vývoje (ontogeneze) a historie artefaktů je obdobou přirozené historie (evoluce). Rozdíly se týkají variací, přenosu a výběru.

------------

The history of mousetraps is not (yet) an established subject of research in the history of material culture.

This ignorance has allowed Michael Behe (1996) to argue for the ubiquitous flat trap as an example of a system that seemingly could not have evolved. These traps cannot catch mice with a missing part.

From this simple fact, which is called irreducible complexity, Behe drew a triple-jump conclusion: 1.) irreducibly complex systems cannot have any working ancestor with one less part; 2.) therefore they cannot have a continuous history; 3.) therefore they cannot evolve.

This anti-Darwinian challenge provides a closer look at the history of mousetraps, which is particularly relevant to the study of material culture.

Part I (Refuting Behe's Three-Step Conclusions) of this paper demonstrates that Behe's conclusions are wrong at every step: 1.) A key precursor to the current flat traps had one less part. 2.) The history of mousetraps is continuous and very old. 3.) All the prerequisites for evolution are present in mousetrap populations.

Part II (Evolution of Material Culture) provides the basis for a case study on material culture change. This discussion is currently in full swing regarding evolutionary archaeology (e.g., O'Brien and Lyman 2004; Gabora 2006). Here, mousetraps can bridge the gap between artifacts that are made of only one part (e.g., stone tools) and highly sophisticated machines with large numbers of parts (e.g., steam engines, cars, and computers), and can bridge the Bronze Age to the present. Finally, Part I illustrates why all of Behe's conclusions are false, and Part II why it is possible to freely discuss the pros and cons of the evolution of material culture without feeling pressured to take sides by creationist claims. However, a conceptual framework is needed at the outset. Conceptual framework The production of artifacts is analogous to development (ontogeny) and the history of artifacts is analogous to natural history (evolution). The differences concern variation, transmission, and selection.

VARIACE/VARIATION:

Kulturní variace není ani slepá, ani jasnovidná. Producenti věrně nereprodukují artefakty ani je slepě nemění. Kulturní přenos není přesné kopírování, ale napodobování v kombinaci s lidskými cíli. Tato individuální „teleologie“ zajišťuje, že varianty jsou funkční. Boyd a Richerson (1985) o tom hovoří jako o řízené variantě. Funkční varianta však nemusí být přenesena, protože lidským návrhářům chybí jasnozřivost (Mesoudi et al. 2004; Nelson 2007; Mesoudi 2008).

---------

Cultural variation is neither blind nor clairvoyant. Producers do not faithfully reproduce artifacts or blindly alter them. Cultural transmission is not exact copying, but imitation combined with human goals. This individual "teleology" ensures that the variants are functional. Boyd and Richerson (1985) refer to this as directed variation. However, functional variation may not be transferred because human designers lack clairvoyance (Mesoudi et al. 2004; Nelson 2007; Mesoudi 2008).

PŘENOS/TRANSMISSION:

Cavalli-Sforza a Feldman (1981) rozlišují vertikální od šikmého a horizontálního přenosu kulturních rysů. Vertikální přenos probíhá mezi příbuznými jednotlivci (např. Rodič - potomek). Běží paralelně s přenosem ze zárodečné linie. Horizontální přenos probíhá mezi nepříbuznými jedinci stejné generace (např. Spolužáky). Šikmý přenos probíhá mezi nepříbuznými jednotlivci různých generací (např. Učitel – student). Při rekonstrukci historie artefaktů je však nutné navázat vztahy artefaktů spíše než jejich producentů. Používají se proto poněkud odlišné koncepty. K sestupnému přenosu dochází, pokud je artefakt zkopírován s menšími variacemi, ale žádné části nejsou vypůjčené z jiných artefaktů. Například klec klece se zkopíruje, aniž by se mechanismus set / uvolnění nahradil jiným z jiného druhu pasti, a to tak pro všechny součásti. Ačkoli tento přenos sestupuje po linii pastí v klecích, nemusí být dotyční producenti geneticky příbuzní. Klesající přenos se shoduje pouze s vertikálním přenosem, pokud jsou výrobci spřízněni. Podobně se boční přenos dílů mezi artefakty liší od horizontálního přenosu. K bočnímu přenosu dochází, pokud je například do lapače choker zaveden mechanismus set / release z lapače klecí. Ačkoli tento přenos překračuje hranici mezi systémy artefaktů, které uživatelé vnímají jako různé druhy, dotyční vynálezci mohou být geneticky příbuzní. Vynálezce mohl dokonce znovu zkombinovat části různých artefaktů, které si sám vynalezl. Jednalo by se o boční přenos částí, přestože jsou vynálezci geneticky identičtí. Boční přenos není ani míchání. Prolínání dědičnosti znamená, že fenetické výrazy potomků jsou průměrem předků a že v pozdějších synovských generacích nemůže dojít k segregaci. Míchání ničí variace (viz Cavalli-Sforza a Feldman 1981). Za předpokladu smíšeného dědictví Fleming Jenkin (1867) skvěle vyvrátil Darwinův původ druhů, protože „tento sport bude zaplaven čísly a po několika generacích bude jeho zvláštnost vyhlazena“. Příčný přenos dílů mezi systémy však vytváří nové varianty a nevylučuje samostatný přenos jednou kombinovaných dílů později. Jde tedy o formu rekombinace, i když spíše o nerovnoměrnou a nepravidelnou, která se vyskytuje spíše u prokaryot než u sexuálních organismů (Wimsatt 1999). Rekombinace mezi technologickými systémy je velmi důležitá, téměř podstatou vynálezu. I když k tomu často dochází mezi podobnými artefakty (např. Klecovými a chokerovými pastmi), neexistuje žádné omezení pro rekombinaci mezi artefakty s různými účely.

-------------

Cavalli-Sforza and Feldman (1981) distinguish vertical from oblique and horizontal transmission of cultural traits. Vertical transmission occurs between related individuals (e.g., parent-offspring). It runs parallel to germline transmission. Horizontal transmission runs between unrelated individuals of the same generation (e.g., classmates). Oblique transmission runs between unrelated individuals of different generations (e.g., teacher-student). In reconstructing the history of artifacts, however, it is necessary to establish the relationships of artifacts rather than their producers. Somewhat different concepts are therefore used. Descending transmission occurs when an artefact is copied with minor variations but no parts are borrowed from other artefacts. For example, a cage trap is copied without replacing the set/release mechanism with another from a different trap type, and so for all parts. Although this transfer descends down the line of cage traps, the producers in question may not be genetically related. Downward transmission only coincides with vertical transmission if the producers are related. Similarly, lateral transfer of parts between artifacts differs from horizontal transfer. Lateral transfer occurs when, for example, a set/release mechanism from a cage trap is introduced into a choker trap. Although this transfer crosses the boundary between artifact systems that users perceive as different species, the inventors in question may be genetically related. An inventor could even recombine parts of different artifacts that he himself invented. This would be a lateral transfer of parts, even though the inventors are genetically identical. Lateral transfer is not even mixing. Hereditary intermingling means that the phenetic expressions of the descendants are the average of the ancestors and that segregation cannot occur in later filial generations. Mixing destroys variation (see Cavalli-Sforza and Feldman 1981). Assuming mixed inheritance, Fleming Jenkin (1867) famously refuted Darwin's origin of species because "the sport will be swamped with numbers, and after a few generations its peculiarity will be obliterated." However, the transverse transfer of parts between systems creates new variations and does not preclude the separate transfer of once-combined parts later. It is thus a form of recombination, albeit a patchy and irregular one that occurs in prokaryotes rather than sexual organisms (Wimsatt 1999). Recombination between technological systems is very important, almost the essence of invention. While this often occurs between similar artifacts (e.g., cage and choker traps), there is no limit to recombination between artifacts with different purposes.

VÝBĚR/CHOICE:

Přirozený výběr je nevyhnutelným důsledkem konkurence mezi jednotlivci s dědičnými změnami kondice.

Nic aktivně nedělá výběr. Kulturní výběr je však způsoben hodnotami, které mohou mít výrobci, prodejci i uživatelé. Richerson a Boyd (2005) rozlišují předpojatý přenos od výběru. Předsudky v přenosu jsou způsobeny preferencemi jednotlivců a výběr je způsoben účinkem, který má přijetí kulturní varianty na šanci napodobit. Některé hodnoty způsobující kulturní výběr prostřednictvím předsudků o přenosu jsou identifikovány níže. Níže se nebudeme zabývat otázkou, jak mohlo přijetí lepší pastí na myši ovlivnit přežití (přirozený výběr) lidí.

----------------------

Natural selection is the inevitable result of competition between individuals with heritable fitness variations.

Nothing actively makes selection. However, cultural selection is caused by the values that producers, sellers, and users may hold. Richerson and Boyd (2005) distinguish biased transmission from selection. Bias in transmission is caused by individuals' preferences, and selection is caused by the effect that adopting a cultural variant has on the chance of imitation. Some values causing cultural selection through transmission bias are identified below. We do not address below the question of how the adoption of better mousetraps might have affected the survival (natural selection) of humans.

Homologie, kulturní přenos a zdravý rozum/Homology, cultural transmission and common sense:

Je šetrnější předpokládat společný kulturní fond, ze kterého lze čerpat inspiraci, než tolik konvergentních záblesků geniality, i když si dotyční vynálezci nebyli vždy vědomi svých zdrojů.

Pokud je tedy rozhodnutí mezi bočním převodem a konvergencí, bude laterální převod výchozí, pokud chybí další důkazy o konvergenci. Existují dobré důvody pro tento posun břemene od prokázání homologie k prokázání analogie v pasti.

Na rozdíl od biologických vlastností nebo softwaru (viz Sole, toto vydání), pasti neobsahují jemnou strukturu nebo kód, který může rozhodovat o homologii. Mikroskopické rozdíly oka obratlovců a chobotnic nebo různé počítačové kódy používané pro podobný výkon softwaru dokazují konvergenci. Naopak, drátěné části dvou různých pastí nejsou homologní jen proto, že jejich atomová struktura je identická. Dva pasti nejsou konvergentní jen proto, že jsou vyrobeny z různých materiálů. Vynálezci mají při výběru materiálů svobodu. Mnoho pastí na myši z druhé poloviny dvacátého století tak promývá starší designy pomocí moderních materiálů, jako je lepenka, gumička, plasty nebo obzvláště odolné slitiny oceli (Drummond 2009a). Nelze tedy činit závěr, že každý z vynálezců dospěl k mechanismům svých moderních pastí nezávisle na starších designech. Zkroucená vlákna byla nahrazena drátěnými pružinami nebo gumičkami a dřevěné části kovovými částmi a plasty. Analogická povaha částí neodhaluje, zda byly myšlenky také analogické nebo homologní. Fylogeneze hmoty a informací se mohou lišit. Rozhodování o homologii se zde stává stejně obtížným jako práce patentového úředníka.

Řešení tohoto problému patentovým úředníkem spočívá v tom, že vynálezce je povinen prokázat novost svého designu, což je často nová kombinace starých dílů. Toto řešení souhlasí se zdravým rozumem. Žádný vynálezce nikdy netvrdí, že má starý nápad sdílený s mnoha předchůdci, a nikdo ho nikdy nežádá, aby to dokázal. Je považováno za samozřejmé, že většina nápadů je starých a sdílených. Stejně tak předpokládám společný technologický fond, ze kterého mohou vynálezci volně čerpat inspiraci, pokud neexistují důkazy o konvergenci. Dokonce i rozdíl mezi homologiemi jako sdílenými předky nebo sdílenými odvozenými vlastnostmi se může stát problematickým, když artefakty přetrvávají jako starožitné kousky dlouho poté, co se přestanou používat. Problém je v tom, že artefakt vyhynulý ze skupiny skutečně použitých předmětů může být přesto zachován a může inspirovat nedávné vynálezce.

-----------------------------

It is more benign to assume a common cultural pool from which to draw inspiration than so many convergent flashes of genius, even if the inventors in question were not always aware of their sources.

Thus, if the decision is between lateral transfer and convergence, lateral transfer will be the default in the absence of further evidence of convergence. There are good reasons for this shift in burden from proving homology to proving analogy in the trap.

Unlike biological traits or software (see Sole, this issue), traps do not contain fine structure or code that can decide homology. The microscopic differences of the vertebrate and octopus eye or the different computer codes used to perform similar software demonstrate convergence. Conversely, the wire parts of two different traps are not homologous simply because their atomic structure is identical. Two traps are not convergent just because they are made of different materials. Inventors are free to choose their materials. Thus, many mousetraps from the second half of the twentieth century blend older designs with modern materials such as cardboard, rubber, plastics, or particularly durable steel alloys (Drummond 2009a). Thus, it cannot be concluded that each of the inventors arrived at the mechanisms of their modern traps independently of the older designs. Twisted fibers were replaced by wire springs or rubber bands, and wooden parts by metal parts and plastics. The analogous nature of the parts does not reveal whether the ideas were also analogous or homologous. The phylogeny of matter and information may differ. Deciding homology here becomes as difficult as the job of a patent clerk.

The patent officer's solution to this problem is that the inventor is required to prove the novelty of his design, which is often a new combination of old parts. This solution is consistent with common sense. No inventor ever claims to have an old idea shared with many predecessors, and no one ever asks him to prove it. It is taken for granted that most ideas are old and shared. Likewise, I assume a common pool of technology from which inventors are free to draw inspiration unless there is evidence of convergence. Even the distinction between homologies as shared ancestry or shared derived properties can become problematic when artifacts persist as antique pieces long after they have fallen into disuse. The problem is that an artifact extinct from a group of actually used objects may still be preserved and may inspire recent inventors.

Přepínání perspektiv/Switching perspectives:

Části artefaktů jsou samostatně přenášené prvky kultury (Lagercrantz 1964; O’Brien et al. 2010).

Zatímco uživatelé vybírají celé systémy na základě jejich funkce, vynálezci rekombinují součásti bez ohledu na systémy, ze kterých pocházejí, pokud se zdá, že přináší zlepšení. Můžeme buď přijmout perspektivu fyzických částí a sledovat jejich linii prostřednictvím různých systémů, nebo sledovat linii určitého systému a zaznamenat náhlý výskyt nových částí v důsledku bočního přenosu. Pohled této části může být stejně poučný k otázce vývoje hmotné kultury, jako pohled genů k biologické evoluci, protože by mohl ukázat, jak se užitečná nová část (např. Drátěná pružina) rozšířila do nejrůznějších technických systémů . Navíc by to mohlo odhalit, kde síťovaná fylogeneze obsahuje překrývající se, ale rozvětvující se, fylogeneze částí a kde dochází ke skutečnému míchání. Následující přehled historických záznamů pastí přijímá pohled na funkční systémy (pasti), zatímco z pohledu části je navržena kladistická analýza drátové pružiny.

------------------------

Parts of artifacts are independently transmitted elements of culture (Lagercrantz 1964; O'Brien et al. 2010).

While users select entire systems based on their function, inventors recombine parts regardless of the systems they come from if it seems to bring improvement. We can either adopt the perspective of physical parts and follow their lineage through different systems, or follow the lineage of a particular system and note the sudden appearance of new parts due to lateral transfer. The view of this part could be as instructive to the question of the evolution of material culture as the view of genes is to biological evolution, because it could show how a useful new part (e.g., a wire spring) has spread to a variety of technical systems . Moreover, it could reveal where reticulate phylogeny contains overlapping, but branching, phylogenies of parts and where there is real mixing. The following review of historical trap records adopts a functional systems (traps) view, while a cladistic wire-spring analysis is proposed from a parts perspective.

Upevňovací podmínky/Fixing conditions:

Termíny musí rozlišovat funkce bez ohledu na historické části, které je nesou. Je zbytečné hovořit například o kovové platformě, pokud část nesoucí tuto funkci nebyla kovová nebo nebyla platformou v předchůdcích. Obecné funkce dotyčné pasti na snap myši jsou

1.) úderník,

2.) mechanismus nastavení / uvolnění,

3.) zdroj energie a

4). základna nebo rám, ke kterému lze tyto části pevně připojit.

----------------

The terms must distinguish functions regardless of the historical parts that bear them. It is useless to speak, for example, of a metal platform if the part bearing that function was not metal or was not a platform in its predecessors. The general functions of the snap mouse trap in question are

1.) Striker,

2.) an adjustment/release mechanism,

3.) a power source, and

4). a base or frame to which these parts can be firmly attached.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Část I: Vyvrácení Beheho trojskoků/Part I: Refuting Behe's Triple Jumps:

William Chauncey Hooker (1894) si nechal patentovat ploché pastičky: „pro chytání myší a potkanů jednoduchý, levný a účinný pasti přizpůsobený tak, aby nevzrušoval podezření ze zvířete, a který lze umístit do blízkosti otvoru pro krysy.“ Umožňoval hromadnou výrobu a prošel mnoha úpravami (Drummond et al. 2002).

-----------------------------

William Chauncey Hooker (1894) patented the flat trap: "for catching mice and rats, a simple, cheap, and effective trap adapted so as not to excite suspicion of the animal, and which can be placed near the rat hole." It allowed for mass production and underwent many modifications (Drummond et al. 2002).

Bezpečné nastavení Hookerova designu vynalezl John Mast (podaný 1899, patentovaný 1903): „Úkolem vynálezu je poskytnout prostředky, pomocí kterých lze snadno nastavit nebo upravit pasti této třídy [ploché pasti] absolutní bezpečnost ošetřující osobě, vyhýbání se odpovědnosti za to, že si úderník udeří nebo poraní prsty, pokud dojde k jeho předčasnému nebo náhodnému uvolnění nebo uvolnění. “ Skutečnost, že Hooker v roce 1905 prodal společnost Animal Trap Company z Abingdonu v IL a sloučila se s JM Mast Manufacturing Company v Lititz, PA (Drummond et al. 2002), mohla přispět k falešnému připisování priority Mastu ( Naděje 1996). Bohužel se přenáší nedůvěra v Mastovu prioritu (např. Shanks a Joplin 2000). Jiní falešně připisují prioritu Jamesi Henry Atkinsonovi z Leedsu ve Velké Británii (např. Bellis 2009). Jeho „Malý kleště“ obdržel GB patent č. 27 488 v roce 1899 a má šlapadlo vystřižené z celé šířky základny. Tím se zvyšuje pravděpodobnost, že past bude odpružena, když nad ní myš projde, aniž by byla přitahována k návnadě. Jinou městskou legendou je Hiram Maxim, vynálezce kulometu, jako vynálezce první ploché pasti na myš (např. „Past na myši“ od přispěvatelů z Wikipedie, verze před 6. lednem 2010). Ve svých pamětech však Maxim (1915) popsal své vynálezy jako automatické klecové pasti. Resetovací automatismus jedné byl poháněn vinutou pružinou vyrobenou z obruče sukně a automatiku druhé poháněly samotné vstupující myši.

-----------------

The safe adjustment of Hooker's design was invented by John Mast (filed 1899, patented 1903): 'The object of the invention is to provide a means by which traps of this class [flat traps] may be readily adjusted or adjusted for the absolute safety of the person attending, avoiding liability for the striker striking or injuring his fingers if the trap is prematurely or accidentally released or loosened. " The fact that Hooker sold the Animal Trap Company of Abingdon, IL, in 1905 and merged with the JM Mast Manufacturing Company of Lititz, PA (Drummond et al. 2002) may have contributed to the false attribution of Mast priority ( Hope 1996). Unfortunately, distrust of Mast priority is transmitted (e.g. Shanks and Joplin 2000). Others have falsely attributed priority to James Henry Atkinson of Leeds, UK (e.g. Bellis 2009). His "Little Tongs" received GB Patent No. 27,488 in 1899 and has a treadle cut out of the full width of the base. This increases the likelihood that the trap will be sprung when a mouse passes over it without being attracted to the bait. Another urban legend credits Hiram Maxim, the inventor of the machine gun, as the inventor of the first flat mouse trap (e.g., "Mouse Trap" by Wikipedia contributors, version before January 6, 2010). However, in his memoirs, Maxim (1915) described his inventions as automatic cage traps. The reset automatism of one was driven by a coiled spring made from a hoop skirt, and the automatism of the other was driven by the entering mice themselves.

O jednu část méně: Semenový předchůdce/One less part: The seed progenitor:

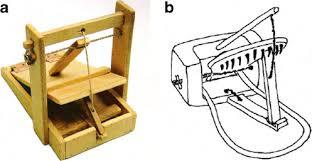

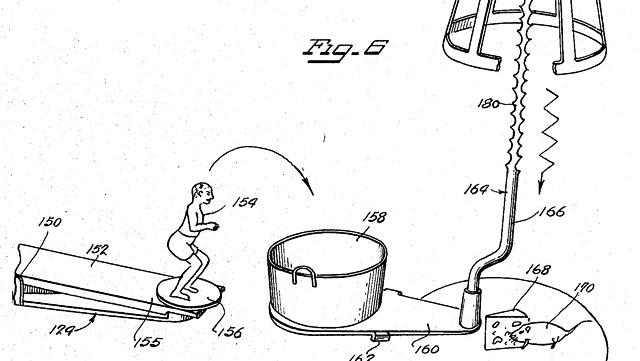

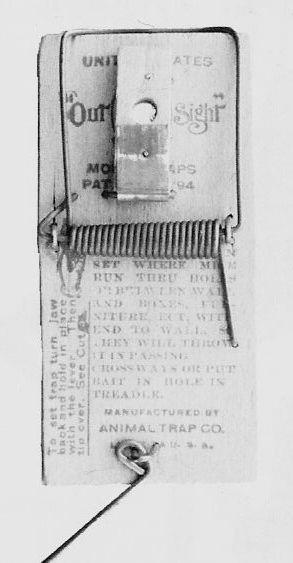

První past na myši založená na Hookerově patentu se jmenovala „Out O‘ Sight “(obr. 1) a byla vyrobena v roce 1894 společností Animal Trap Company v Abingdonu v IL.

----------------------

The first mousetrap based on Hooker's patent was called "Out O' Sight" (Figure 1) and was manufactured in 1894 by the Animal Trap Company in Abingdon, IL.

Hookerův patent. starožitný vzorek „Out O’ Sight “(z Drummond 2005, obr. 23). B Kresba z patentu Hookera (1894).

Drát pružiny / úderníku začíná u # 3,

cívky (# 4),

prochází do úderníku (# 8),

prochází tunelem tvořeným cívkou a končí za úderníkem (# 5).

Části # 6 jsou příslušenství

Tento originální design měl pružinu a úderník vytvořené z jednoho drátu.

Současné ploché záchytné pasti mají samostatnou pružinu a západku, protože jejich výroba a montáž je tímto způsobem jednodušší. Tato konkrétní modifikace však nebyla patentově hodná, protože dříve existovaly i jiné druhy pastí na myši (ne ploché) se samostatnou pružinou a úderníkem. Společný předek všech současných plochých lapaček měl o jednu část méně a velká rozmanitost těchto pastí je dnes způsobena jeho úspěchem. Proto je první závěr Behe špatný. Neredukovatelně složité systémy mohou mít pracovní prekurzory o jednu část méně. Podobné odchylky v počtu dílů se vyskytly v celé historii pasti myši. Neredukovatelná složitost není překážkou pro různé počty dílů přidáním, fúzí nebo oddělením dílů. Jediná věc, která nefunguje, je odebrání části, která nese funkci.

---------------------------

Hooker's patent. Antique specimen "Out O' Sight" (from Drummond 2005, fig. 23). B Drawing from the Hooker patent (1894).

The spring/striker wire starts at #3,

coil (#4),

passes into the striker (#8),

passes through a tunnel formed by the coil and ends behind the striker (#5).

Parts #6 are accessories

This original design had the spring and striker formed from a single wire.

Current flat traps have a separate spring and striker because they are easier to manufacture and assemble this way. However, this particular modification was not patent-worthy because there were other types of mousetraps (not flat) with a separate spring and striker before. The common ancestor of all current flat traps had one less part, and the great variety of these traps today is due to its success. Therefore, Behe's first conclusion is wrong. Irreducibly complex systems can have working precursors with one less part. Similar variations in the number of parts have occurred throughout the history of the mousetrap. Irreducible complexity is not a barrier to varying part counts by adding, merging, or separating parts. The only thing that doesn't work is removing a part that carries a function.

Kontinuální historie: Přímý příběh/Continuum History: A Straightforward Story:

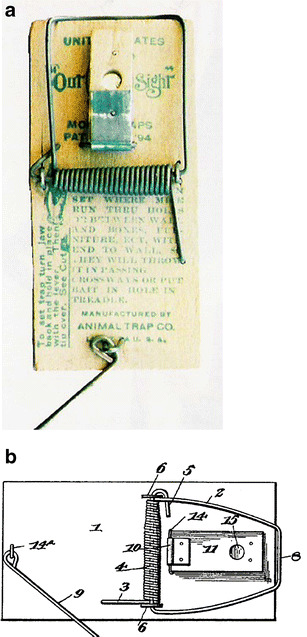

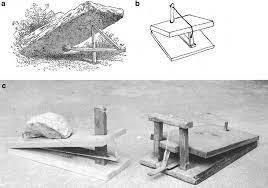

Staroegyptská kultura byla vysoce obrazová a lov pasti byl královským sportem. Chytání hlodavců nebylo žádným královským sportem. Pasti na potkaní klec z keramiky jsou nicméně známy také ze starověkého Egypta (např. Drummond et al. 1990) a jinde.

Skutečnost, že nejstaršími historickými záznamy jsou pasti na ptáky z Egypta, tedy nelze chápat tak, že tyto pasti byly omezeny na Egypt nebo na lov ptáků. Sítě, nástrahy nebo hole poháněné kroucenými vlákny s hroty drtícími lebky (Lagercrantz 1950). Některé starodávné pasti na ptáky byly nápadně podobné pastím na ploché myši (obr. 2a, b). Grdseloff (1938a) a Scott (1940) mají restaurované vzorky. Grdseloff (1938b) identifikoval hieroglyfy pro tento druh pasti a vystopoval je zpět do starého království (2686–2181 př. N. L.). Podobné pasti přežily až do nedávné doby (obr. 2c).

-------------------------

Ancient Egyptian culture was highly figurative and trapping was a royal sport. Rodent trapping was not a royal sport. However, pottery rat traps are also known from ancient Egypt (e.g. Drummond et al. 1990) and elsewhere.

Thus, the fact that the earliest historical records are of bird traps from Egypt should not be taken to imply that these traps were restricted to Egypt or to bird hunting. Nets, lures, or sticks powered by twisted fibers with skull-crushing spikes (Lagercrantz 1950). Some ancient bird traps were strikingly similar to flat mouse traps (Fig. 2a, b). Grdseloff (1938a) and Scott (1940) have restored specimens. Grdseloff (1938b) identified hieroglyphics for this type of trap and traced them back to the Old Kingdom (2686-2181 B.C.). Similar traps have survived into recent times (Figure 2c).

a Rekonstrukce egyptské pasti na lapačku pro ptáky ca. 1550 př. N. L. (Od Schäfer 1918/19, Abb. 100).

b Torzní past zachycená v hrobce 17, Khety, 2125–1985 př. n. l. (Griffiths 1900, deska 22). Pouze jedna strana základny drží zkroucenou šňůru. Viz také Firth a Gunn (1926, s. 6).

c Egyptská past na tleskání, počátek devatenáctého století (od Schäfer 1918/19, obr. 91 a 92).

d All-wire trap inzerovaný jako „Kypr“ společností Orlando Leggett, Ipswich, ca. 1890 (z Drummondu 2008, obr. 11). Název by mohl naznačovat jeho původ ve středomořských pasti na ptáky.

e Výkres celovodičové pasti patentované Frostem (1891).

f Vzorek drotářských pastí, konec devatenáctého století, Velké Rovne, Slovensko, (www.velkerovne.sk/contents/chod07_sk.htm).

g Kresba z tohoto obrázku. A: dřevěná plošina, B: jednotka pružiny / rukojeti, C: úderník, D: přídržná tyč (část mechanismu set / uvolnění), E: háček na návnadu (část mechanismu set / uvolnění), F: přípravky. Jednotka pružiny / rukojeti, úderník a háček na návnadu připomínají spíše Leggetův Kypr než Hookerův Out O ‘Sight.

-------------------------

a Reconstruction of an Egyptian bird trap ca. 1550 BC (From Schäfer 1918/19, Abb. 100).

b Torsion trap depicted in Tomb 17, Khety, 2125-1985 B.C. (Griffiths 1900, Plate 22). Only one side of the base holds a twisted cord. See also Firth and Gunn (1926, p. 6).

c Egyptian clap trap, early nineteenth century (from Schäfer 1918/19, figs 91 and 92).

d All-wire trap advertised as 'Cyprus' by Orlando Leggett, Ipswich, c. 1890 (from Drummond 2008, fig. 11). The name might suggest its origins in Mediterranean bird traps.

e Drawing of the all-wire trap patented by Frost (1891).

f Specimen of a tinker's trap, late nineteenth century, Velké Rovne, Slovakia, (www.velkerovne.sk/contents/chod07_sk.htm).

g Drawing from this picture. A: wooden platform, B: spring/handle unit, C: striker, D: holding bar (part of set/release mechanism), E: bait hook (part of set/release mechanism), F: jig. The spring/handle unit, striker and bait hook are more reminiscent of Legget's Cyprus than Hooker's Out O' Sight.

Pozdější verze byly zcela z drátu. Takové odpružené drátěné lapače se stále používají pro ptáky ve středomořské oblasti. V devatenáctém století byli také propagováni jako pasti na hlodavce.

Ets Julien Aurouze, Paříž, zdobí výlohu svých obchodů vycpanými krysami visícími z těchto pastí už od roku 1872 (viz www.aurouze.fr/deratisation.html). Displej se stal turistickou atrakcí, která se objevila také ve filmu Ratatouille. Aurouzeův online katalog nicméně uvádí tyto pasti jako Piège à oiseaux (past na migrující ptáky). Inzerát Orlanda Leggetta z Ipswiche a patent George Frosta (1891) z kanadského Toronta jim výslovně říkají pasti na krysy. Podobné pasti byly v Německu uváděny na trh jako „pasti na ptáky a myši“ (Drummond and Dagg 2010). Zatímco v „Kypru“ společnosti Legget (obr. 2d) tvoří jedno drátěné držadlo a pružinu, základna čelisti a rukojeť jsou jednotkou v patentu Frosta (obr. 2e). V žádném případě však nebyla pružina a úderník jednoho drátu. Zde, stejně jako jinde, představuje historický záznam paradox, že homologní myšlenky lze kulturně přenášet prostřednictvím analogických struktur. Historický kontext však naznačuje, že tradiční past na tleskání inspirovala vynález takové pasti výhradně z drátu a jeho široký prodej ve Středomoří (Schäfer 1918/19).

-------------------------

Later versions were made entirely of wire. Such spring-loaded wire traps are still used for birds in the Mediterranean area. In the nineteenth century they were also promoted as rodent traps.

Ets Julien Aurouze, Paris, has been decorating its shop windows with stuffed rats hanging from these traps since 1872 (see www.aurouze.fr/deratisation.html). The display has become a tourist attraction that also appeared in the film Ratatouille. Aurouze's online catalogue, however, lists these traps as Piège à oiseaux (traps for migrating birds). An advertisement by Orlando Leggett of Ipswich and a patent by George Frost (1891) of Toronto, Canada, explicitly call them rat traps. Similar traps were marketed in Germany as "bird and mouse traps" (Drummond and Dagg 2010). While the Legget "Cyprus" (Figure 2d) consists of a single wire handle and spring, the jaw base and handle are the unit in the Frost patent (Figure 2e). In neither case, however, were the spring and striker of a single wire. Here, as elsewhere, the historical record presents the paradox that homologous ideas can be culturally transmitted through analogous structures. However, the historical context suggests that the traditional clap trap inspired the invention of such a trap made entirely of wire and its widespread sale in the Mediterranean (Schäfer 1918/19).

To znamená, že myšlenka ploché pasti byla kulturně přenášena. Niles Eldredge (např. Tëmkin a Eldredge 2007) označuje úmyslný vynález alternativních realizací jako „princip Hannah“. V širším smyslu je Hannahův princip extrémním případem bočního přenosu, kdy jsou vyměňovány všechny části trapového systému současně. V užším slova smyslu vyžaduje analogické řešení výměna hmotných dílů. Například zkroucený kabel torzních lapačů byl nahrazen stočeným drátem. Hlavním úspěchem (a problémem zachování) tohoto designu zůstává dnešní odchyt pěvců (viz webová stránka „Lega Italiana Protezione Ucelli“). Možná jsou ptáci obzvláště nic netušící proti návnadě sedící na drátěné konstrukci připomínající větvičku. Jeho použití jako pasti na ptáky může také vysvětlit, proč byl tento design stěží rozpoznán jako součást historie pasti na myši. Připevnění úderníku, pružiny a mechanismu nastavení / uvolnění na dřevěném podstavci však poskytuje tradiční past na myši (obr. 2f, g). V devatenáctém století prodávali drotáři své zboží po celém světě (Drummond and Dagg 2010). Slovenští drotáři (Drotári) se dokonce dostali do Ameriky během až osmiletých cest (Ginzler, nepublikováno). Poznámka pod čarou 1 Od roku 1870 se do USA navždy přistěhovalo stále více Slováků. Shodou okolností jejich oblíbenými cíli byly severovýchod a středozápad, včetně Pensylvánie a Illinois.

-----------------------

This means that the idea of the flat trap has been culturally transmitted. Niles Eldredge (e.g. Tëmkin and Eldredge 2007) refers to the deliberate invention of alternative realisations as the 'Hannah principle'. In a broader sense, the Hannah principle is an extreme case of lateral transmission, where all parts of a trap system are exchanged simultaneously. In a narrower sense, the replacement of material parts requires an analogous solution. For example, the twisted cable of the torsion traps was replaced by a twisted wire. The main success (and conservation problem) of this design remains today's trapping of songbirds (see the website "Lega Italiana Protezione Ucelli"). Perhaps birds are particularly unsuspecting of a decoy sitting on a twig-like wire structure. Its use as a bird trap may also explain why this design has hardly been recognized as part of the history of the mousetrap. However, the attachment of the striker, spring, and adjustment/release mechanism on the wooden base provides a traditional mousetrap (Figure 2f, g). In the nineteenth century, tinkers sold their wares around the world (Drummond and Dagg 2010). Slovak tinkers (Drotári) even made their way to America during journeys of up to eight years (Ginzler, unpublished). Footnote 1 Since the 1870s, more and more Slovaks have immigrated to the United States permanently. Coincidentally, their favorite destinations were the Northeast and Midwest, including Pennsylvania and Illinois.

Tinkerová past (obr. 2f) se liší od Hookerova patentu. Pružina a západka nejsou vytvořeny z jedné části; pružina má odvinutou střední část, která vypadá jako rukojeť lapače podobného Kypru (viz obr. 2d, e); mechanismus set / release má spíše než pedál háček na návnadu, jako v pasti na tleskání ptáků a na Kypru.

Pokud jsou zahrnuty konkrétně kulturní způsoby přenosu informací, sestup z torzních pastí z doby bronzové do současných plochých pastí nevykazuje žádné velké skoky v designu. Výměna dřeva a vláken za drát si vyžádala změnu ze zkrouceného na vinutý zdroj energie, který v užším smyslu ilustruje princip Hannah. Historie je zde stejně nepřetržitá jako později, když drotáři vyměnili základní drátěnou čelist za dřevěnou plošinu, která přeměnila skutečnou past na ptáky na skutečnou past na myš. Otázka metaúrovně, jak se k nám historické záznamy dostaly, spíše než to, jak byly artefakty přeneseny v minulosti, odhaluje rekonstrukci, reverzní inženýrství a dekódování (jazyk) jako další způsoby přenosu informací. Tento seznam zdaleka nevyčerpává prostředky cestování časem (zotavení), které mají kulturní informace (např. Archivace, výkop a ochrana). Spící kulturní informace se mohou znovu začít používat (Wimsatt 1999). Kontinuita historie artefaktů tedy neznamená jednotně tikající hodiny kulturních změn.

-------------------------

The Tinker trap (Figure 2f) is different from the Hooker patent. The spring and latch are not made of one part; the spring has a coiled central part that looks like the handle of a Cyprus-like trap (see Figure 2d, e); the set/release mechanism has a bait hook rather than a pedal, as in the bird-clapping trap and the Cyprus.

When specifically cultural modes of information transmission are included, the descent from Bronze Age torsion traps to contemporary flat traps shows no major leaps in design. The replacement of wood and fiber with wire necessitated a change from a twisted to a coiled energy source, which in a narrower sense illustrates the Hannah principle. The history here is as continuous as later when tinkers replaced the basic wire jaw with a wooden platform that transformed a real bird trap into a real mousetrap. The meta-level question of how the historical record came to us, rather than how artifacts were transmitted in the past, reveals reconstruction, reverse engineering, and decoding (language) as other ways of transmitting information. This list by no means exhausts the means of time travel (recovery) that cultural information has (e.g., archiving, excavation, and preservation). Dormant cultural information can be put to use again (Wimsatt 1999). Thus, the continuity of artifact history does not imply a uniformly ticking clock of cultural change.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Evoluce: Všechny předpoklady jsou hojné a pasti všichni zbožňujeme/Evolution: All prerequisites are abundant and we all adore traps:

Nezvažujeme zde otázku, zda je historie pastí myší ve skutečnosti případem evoluce, ale zda nemůže být v zásadě evoluční, jak tvrdil Behe (1996).

-------------------------

We do not consider here the question of whether the history of mousetrapping is in fact a case of evolution, but whether it may not be fundamentally evolutionary, as argued by Behe (1996).

Variace/Variation:

Společnost Animal Trap Company, Lititz, PA vyrobila více než 30 variant lapačů variant a 13 variant mechanismů set / release (Drummond et al. 2002). Ostatní společnosti, země, časy a pasti vykazují stejnou variabilitu (zaznamenanou zejména Lagercrantzem 1950, 1964, 1966, 1972, 1984, 1987) a Drummondem (2004a, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009a, b). Například Drummond (2005) obsahuje více než 60 variant britských plochých pastí na myši.

-----------------------------------------

The Animal Trap Company, Lititz, PA has produced over 30 trap variants and 13 variants of set/release mechanisms (Drummond et al. 2002). Other companies, countries, times, and traps show the same variability (noted especially by Lagercrantz 1950, 1964, 1966, 1972, 1984, 1987) and Drummond (2004a, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009a, b). For example, Drummond (2005) lists more than 60 variants of British flat mouse traps.

PŘENOS/TRANSMISSION:

„Out O’ Sight “si zachoval starý design pružiny a úderníku vyrobeného z jednoho drátu (viz obr. 1).

Podobné případy přenosu by mohly být poskytnuty i pro jiné druhy pastí.

Kyperské pasti si uchovaly návnadový hák starověké torze a tradičních pastí na tleskání. Laterální přenosy jsou samozřejmě také případy přenosu, ačkoli procházejí kategoriemi, které uživatelé vnímají jako různé druhy artefaktů.

------------------------

The "Out O' Sight" retains the old one-wire spring and firing pin design (see Figure 1).

Similar transfer cases could be available for other types of traps.

The Cyprus traps retain the baited hook from the old torsion and traditional clapper traps. Lateral transfers are also, of course, transfer cases, although they pass through categories that users perceive as different kinds of artifacts.

VÝBĚR/CHOICE:

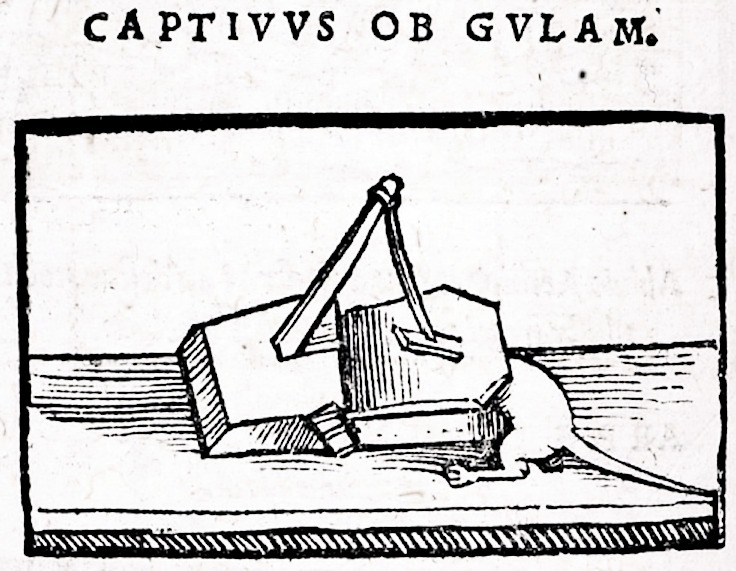

Například zdroj torzní energie využívající zkroucené vlákno byl nahrazen drátěnými pružinami.

Mascallův záznam z roku 1590 ukazuje, že renesanční torzní pasti (obr. 4) existovaly vedle pasti využívající odvinutou drátěnou pružinu (obr. 5a). Torzní síla přežila až do konce devatenáctého století v egyptských lapačských pastech (obr. 2c; Schäfer 1918/19), než ji nahradila vinutá drátěná pružina. V dnešní době se zdá, že zdroj torzní energie je zcela vyhynulý, s výjimkou možnosti relikvií v některých vzdálených oblastech.

----------------------------

For example, the torsional energy source using twisted fibre has been replaced by wire springs.

Mascall's record of 1590 shows that Renaissance torsion traps (Figure 4) existed alongside a trap using a coiled wire spring (Figure 5a). The torsion force survived until the end of the nineteenth century in Egyptian traps (fig. 2c; Schäfer 1918/19) before it was replaced by the coiled wire spring. Today, the source of torsional power seems to be completely extinct, except for the possibility of relics in some remote areas.

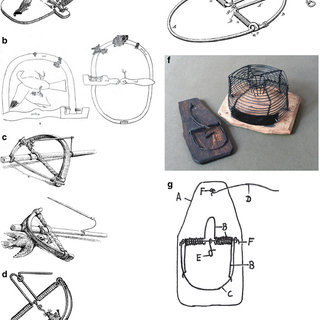

Pasti zabíjející pádem na oběť.

a = past „figurky čtyři“ (od Gibson 1880, s. 107).

b Prefabrikovaná „Čtvercová past na mouce“ (zaznamenaná Mascallem 1590. Rekonstrukce z Drummondu 1992, obr. 1f).

c Vzorky prefabrikovaných pastí pro mrtvý pád z Tyrolska (od Gasser 1988, obr. 44).

--------------------------------------------------

Traps that kill by falling on the victim.

a = "figure four" trap (from Gibson 1880, p. 107).

b Prefabricated 'Square flour trap' (recorded by Mascall 1590. Reconstruction from Drummond 1992, fig. 1f).

c Samples of prefabricated deadfall traps from Tyrol (from Gasser 1988, fig. 44).

Renesanční torzní pasti, Mérodova nebo „Následující“ past (zaznamenaná Master of Flemalle, 1425 Mascall 1590). Replika od Drummonda (2005, obr. 18). Mascallův „Dragin trappe“ (Drummond 1992, obr. 2b). Útočník napájel zkroucený kabel

---------------------------

Renaissance torsion trap, Mérode's or 'Following' trap (recorded by the Master of Flemalle, 1425 Mascall 1590). Replica by Drummond (2005, fig. 18). Mascall's "Dragin trappe" (Drummond 1992, fig. 2b). The attacker fed a twisted cable

Pasti s pružinou a úderníkem z jednoho drátu.

a levá strana: „Dragin trappe with great wyar“ od Mascall (1590, s. 75); vpravo: replika od Drummonda (2005, obr. 19b).

b Polská „Planchette“ (upraveno v Lagercrantz 1987, obr. 5).

c Francouzská „Planchette“ (upraveno v Lagercrantz 1987, obr. 4).

d Viktoriánský „Break back“ (z Drummondu 2008, obr. 12e). Horace Tinker „Malý obr“ patentovaný v roce 1882 (Drummond 2009b, obr. 1).

f Kresba od Andersona (1890, viz také Castle 1888, Andrews 1891, Troumble 1892, Wells 1892).

g Kresba z Hookera (1879). Lapač krtků s rámem (A, g, A, A), pružinou (d) a úderníkem (A, b, e) vyrobeným z jednoho drátu (z Hooker 1879). Když je háček na návnadu (E) posunut doleva, útočník zaklapne nahoru (tečkovaná čára)

----------------------------

Traps with spring and striker made of one wire.

and left: 'Dragin trappe with great wyar' by Mascall (1590, p. 75); right: replica by Drummond (2005, fig. 19b).

b Polish 'Planchette' (adapted from Lagercrantz 1987, fig. 5).

c French 'Planchette' (modified in Lagercrantz 1987, fig. 4).

d Victorian "Break back" (from Drummond 2008, fig. 12e). Horace Tinker's "Little Giant" patented in 1882 (Drummond 2009b, fig. 1).

f Drawing by Anderson (1890, see also Castle 1888, Andrews 1891, Troumble 1892, Wells 1892).

g Drawing from Hooker (1879). mole trap with frame (A, g, A), spring (d) and striker (A, b, e) made of a single wire (from Hooker 1879). When the bait hook (E) is moved to the left, the striker snaps up (dotted line)

Synopse. Zjednodušená historie, každý řádek znamená linii části:

základna v černé barvě; zdroj energie ve světle šedé barvě; útočník v tmavě šedé barvě; mechanismus nastavení / uvolnění přerušovaný; pružinová / úderníková jednotka v šedé barvě. Důležité události:

1: přidat dřevěnou základnu a stropní nosník, upravit mechanismus nastavení / uvolnění;

2: přenést zkroucený kabel do strany;

3: přidat následující štáby;

4: upravte rám, vyměňte zkroucený kabel za otočný, vložte přímo úderník;

5: vyměňte zkroucenou šňůru za drátěnou pružinu s úderovou deskou připevněnou ke střední části se smyčkou, vyměňte mechanismus nastavení / uvolnění; 5a: boční přenos drátěné pružiny;

6: zmenšit desku úderníku a upravit střední smyčku pružiny tak, aby poskytovala jednotku pružiny / úderníku, změnit mechanismus nastavení / uvolnění;

7: spirálová pružina, úprava rámu a mechanismus nastavení / uvolnění;

8: zmenšit rám na rovnou základnu, upravit mechanismus nastavení / uvolnění;

9: rozdělte jednotku pružiny / úderníku na samostatné části; I: nahradit clap-bow úderníkem, upravit rám, změnit mechanismus set / release; II: Princip Hannah: nahrazení dřeva a vláken kovovými částmi (boční převody nejsou zobrazeny); IIa: Transformace pružiny / úderníku na jednotku pružiny / rukojeti (viz „Pohled z části“ níže); III: namontujte čelist, pružinu a mechanismus nastavení / uvolnění na podlouhlý dřevěný podstavec; IV: Vyměňte háček s návnadou za šlapadlo.

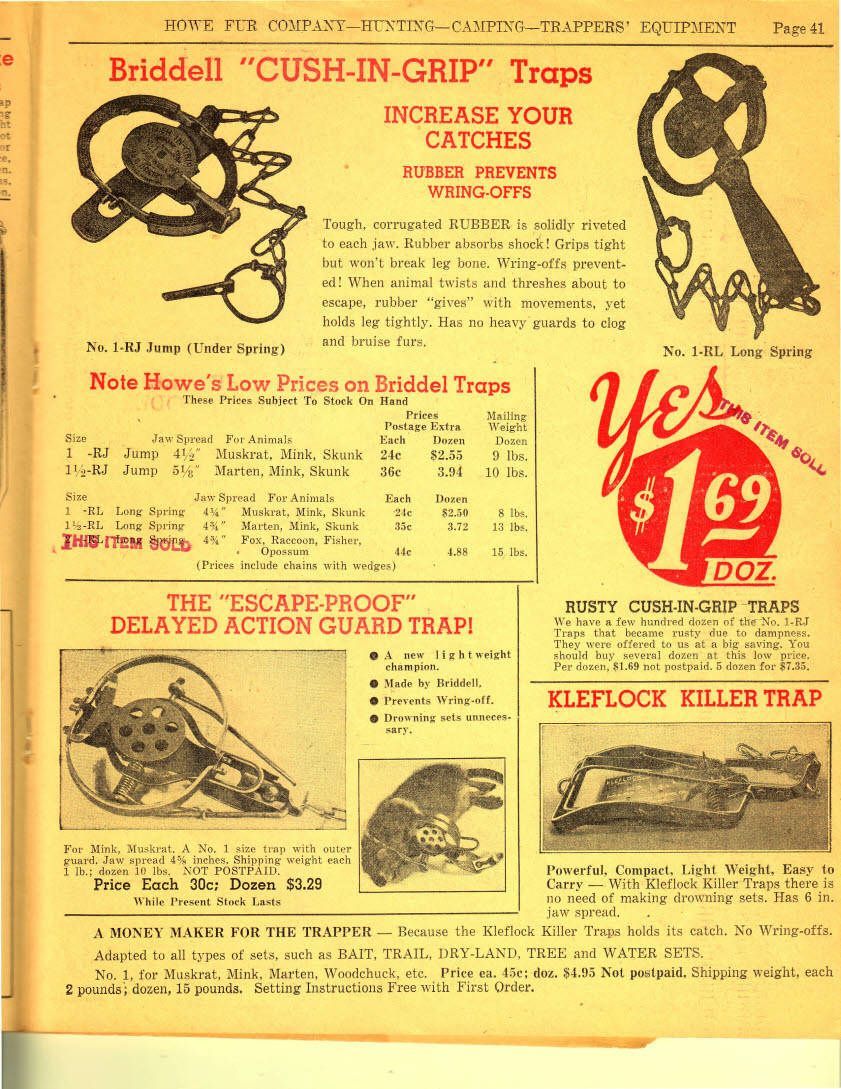

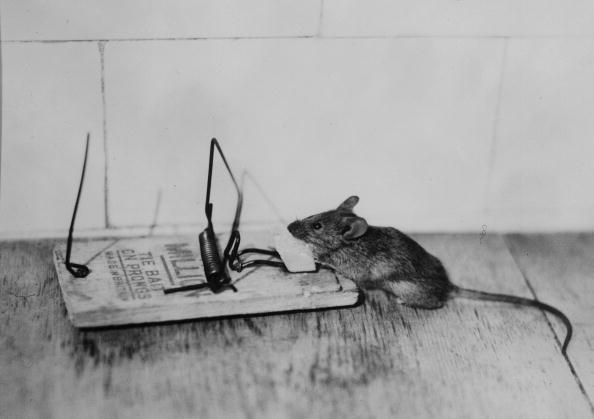

Diferenciální reprodukci lze vyjádřit jako poměr podaných patentů k použitým patentům. Vynálezci bohužel nemají tendenci blíže specifikovat patenty než „past na zvířata“, aby ponechali své možnosti otevřené. Drummond (2004b) Poznámka pod čarou 2 identifikovala v zásadě 4 593 amerických patentů vhodných pro pasti na myši, z nichž 165 bylo použito ve 149 skutečně vyrobených pasti na myši. Komerčně úspěšné pasti však používaly pouze sedm patentů.

Proto byly použity 4% přihlášených patentů a 5% použitých patentů bylo komerčně úspěšných. Tyto údaje se docela dobře srovnávají s odhadem amerického komisaře pro patenty Samuela S. Sparkse z roku 1869, že 10% všech patentů (nejen pastí na myši) mělo určitou komerční hodnotu (Basalla 1988). Výběr mezi patenty na past na myši může být tužší než mezi patenty obecně kvůli populární citaci připisované jedné z přednášek Ralpha Walda Emersona z jara 1871 (Adams 1947): „Pokud člověk dokáže napsat lepší knihu, kázat lepší kázání nebo učinit lepší past na myši než jeho soused, i když si staví svůj dům v lese, svět udělá vyšlapanou cestu k jeho dveřím. “ Mnoho vynálezců pastí na myši bylo upuštěno, aby nenašli žádnou takovou cestu k jeho dveřím. Basalla (1988) ukázal, že kulturní hodnoty jsou klíčovou složkou úspěchu (výběru) artefaktů.

Název „Out O’ Sight “označuje jednu takovou hodnotu. Pasti bylo možné umístit, pokud by je návštěvníci neviděli, na rozdíl od pastí v kleci, chokerů a pastí na mrtvý pád, které dominovaly scéně dříve (Hornell 1940; Hellwig, nepublikovaná poznámka pod čarou 3). Když se rozběhla hromadná výroba, její levnost také umožnila odhodit past spolu s mrtvým tělem, což je pro obyvatele měst pravděpodobně vysoká kulturní hodnota. Všechny dřívější typy pastí vyžadovaly manipulaci s myšmi a často důkladné čištění pastí pro opakované použití.

Vzhledem k tomu, že myši v klecích byly obvykle utopeny nebo umíráni hladem, byly tyto pasti méně humánní, než se na první pohled může zdát. Další moderní kulturní hodnotou je horní povrch plochých lapačů jako prostor pro reklamu (viz obr. 1a; Drummond et al. 2002). Je zajímavé, že tyto kulturní hodnoty se netýkají funkce odchytu. Na jedné straně je plochým povrchem, který lze použít pro reklamu, spandrel (Gould a Lewontin 1979; Sole, toto vydání). Na druhou stranu reklama ovlivňuje výběr spotřebitele a dostupnost takových povrchů ovlivňuje výběr dodavatele.

---------------------------------

Synopsis. Simplified history, each line represents a part line:

base in black; power source in light gray; striker in dark gray; setting/release mechanism intermittent; spring / striker unit in grey. Important events:

1: add wooden base and ceiling beam, adjust setting/release mechanism;

2: transfer the twisted cable to the side;

3: add the following staffs;

4: modify the frame, replace the twisted cable with a rotating one, insert the firing pin directly;

5: replace the twisted cord with a wire spring with a strike plate attached to the middle part with a loop, replace the adjustment / release mechanism; 5a: wire spring lateral transmission;

6: reduce the firing pin plate and modify the middle spring loop to provide a spring/firing unit, change the setting/release mechanism;

7: coil spring, frame adjustment and adjustment/release mechanism;

8: reduce the frame to a straight base, adjust the adjustment / release mechanism;

9: divide the spring / striker unit into separate parts; I: replace the clap-bow with a striker, adjust the frame, change the set / release mechanism; II: Hannah principle: replacement of wood and fibers with metal parts (side gears not shown); IIa: Transformation of the spring / firing pin into a spring / handle unit (see "Sectional View" below); III: mount the jaw, spring and adjustment/release mechanism on the elongated wooden base; IV: Replace the baited hook with a pedal.

Differential reproduction can be expressed as the ratio of patents filed to patents used. Unfortunately, inventors don't tend to specify patents more closely than an "animal trap" to keep their options open. Drummond (2004b) Footnote 2 identified essentially 4,593 US patents suitable for mousetraps, of which 165 were used in 149 mousetraps actually manufactured. However, commercially successful traps used only seven patents.

Therefore, 4% of applied patents were used and 5% of applied patents were commercially successful. These figures compare quite well with the 1869 estimate by US Patent Commissioner Samuel S. Sparks that 10% of all patents (not just mousetraps) had some commercial value (Basalla 1988). The choice among mousetrap patents may be tougher than among patents in general because of a popular quote attributed to one of Ralph Waldo Emerson's spring 1871 lectures (Adams 1947): "If a man can write a better book, preach a better sermon, or make a better mousetrap than his neighbor, though he builds his house in the woods, the world makes a well-trodden path to his door. ” Many inventors of mousetraps have been dropped to find no such way to his door. Basalla (1988) showed that cultural values are a key component in the success (selection) of artefacts.

The name "Out O' Sight" indicates one such value. Traps could be placed out of sight of visitors, unlike the cage traps, chokers, and deadfall traps that dominated the scene earlier (Hornell 1940; Hellwig, unpublished footnote 3). When mass production took off, its cheapness also allowed the trap to be discarded along with the dead body, probably of high cultural value to urban dwellers. All earlier types of traps required handling of mice and often thorough cleaning of the traps for repeated use.

Since caged mice were usually drowned or starved to death, these traps were less humane than they might first appear. Another modern cultural value is the upper surface of flat traps as a space for advertising (see Fig. 1a; Drummond et al. 2002). Interestingly, these cultural values do not relate to the trapping function. On the one hand, a flat surface that can be used for advertising is the spandrel (Gould and Lewontin 1979; Sole, this issue). On the other hand, advertising influences consumer choice, and the availability of such surfaces influences supplier choice.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Část II: Evoluce hmotné kultury/Part II: The Evolution of Material Culture:

Zbývající část tohoto příspěvku rozšiřuje perspektivu o více než jednu linii a diskutuje o důsledcích pro vývoj hmotné kultury.

------------

The remainder of this paper extends the perspective along more than one line and discusses the implications for the development of material culture.

Evolventní příběh/An evolving story:

Pokud se níže uvedené důkazy považují za rodovou linii, musí boční přemostění nutně překlenout zjevné skoky v designu.

Princip šetrnosti naznačuje předpokládat co nejméně případů bočního přenosu. To nemusí být dobrý princip pro historii pastí myší poté, co v roce 1871 došlo k Emersonovu efektu (viz výše). Pro největší část historie se to však zdá docela rozumné.

---------------------------

If the evidence below is considered ancestral, lateral bridging must necessarily bridge the obvious leaps in design.

The principle of parsimony suggests assuming as few cases of lateral transmission as possible. This may not be a good principle for the history of mousetraps after the Emerson effect occurred in 1871 (see above). However, for most of history it seems quite reasonable.

Nástrahy na způsob pádu - ad hoc/Traps on the way of falling - ad hoc:

Ad hoc pasti jsou postaveny (alespoň částečně) z materiálu nalezeného v blízkosti místa, kde působí.

Tyto přírodní faktory, jak Basalla (1988) nazývá vynálezy přirozeně se vyskytujících věcí, nemají tendenci zanechávat dlouhodobé historické záznamy (Hoffecker 2005).

To znamená, že mohou být mnohem starší, než naznačují jejich nejranější záznamy.

Ad hoc pasti pro mrtvý pád jsou neredukovatelné jednoduchosti skládající se z potulné desky nebo jiného těžkého předmětu jako útočníka, některé tyče jsou uspořádány tak, aby to držely, ale aby ustoupily rušení (mechanismus set / uvolnění) a návnadě. V nejjednodušším případě se mechanismus set / release skládá z jedné tyčinky nebo jiného předmětu, který také drží návnadu. Citlivější mechanismy set / release se skládají z několika tyčinek a někdy i strun. Například uspořádání tyčinek „číslo čtyři“ (obr. 3a) je velmi rozšířené. Mascall (1590) to zaznamenal jako „Samson poste for Rattes“. Zatímco Mascallův popis a ilustrace nemusí být samy o sobě dostatečně jasné, Lagercrantz (1984) objasnil problém a poukázal na to, že „Samsonův příspěvek“ byl běžný název pro pasti číslo čtyři. Pokud je útočníkem poleno, základnou je obvykle další poleno a vzpřímené sloupky na obou stranách zabraňují úderníkovi ve zmeškání základny (viz Gibson 1880, s. 114). Lagercrantz (1972) hodnotí ad hoc pasti mrtvého pádu v různých kulturách s různými útočníky a různými mechanismy set / release. Představuje 18 variant, z nichž pouze jedna ukazuje design číslo čtyři z obr. 3a a žádná jako Gibson (1880, s. 114).

-----------------------------------------

Ad hoc traps are built (at least in part) from material found near where they operate.

These natural factors, as Basalla (1988) calls inventions of naturally occurring things, do not tend to leave long-term historical records (Hoffecker 2005).

This means they may be much older than their earliest records suggest.

Ad hoc deadfall traps are irreducible simplicities consisting of a roving board or other heavy object as the striker, some rods arranged to hold it but yield to disturbance (set/release mechanism) and bait. In the simplest case, the set / release mechanism consists of a single rod or other object that also holds the bait. More sensitive set / release mechanisms consist of several rods and sometimes strings. For example, the "number four" stamen arrangement (Fig. 3a) is very widespread. Mascall (1590) recorded it as "Samson poste for Rattes". While Mascall's description and illustration may not be clear enough on their own, Lagercrantz (1984) clarified the issue, pointing out that "Samson's post" was a common name for trap number four. If the striker is a log, the base is usually another log, and upright posts on either side prevent the batter from missing the base (see Gibson 1880, p. 114). Lagercrantz (1972) evaluates ad hoc deadfall traps in different cultures with different attackers and different set/release mechanisms. It presents 18 variants, of which only one shows the design number four of Fig. 3a and none like Gibson (1880, p. 114).

Prefabrikované pasti na způsob smrtícího pádu/Prefabricated death-fall traps:

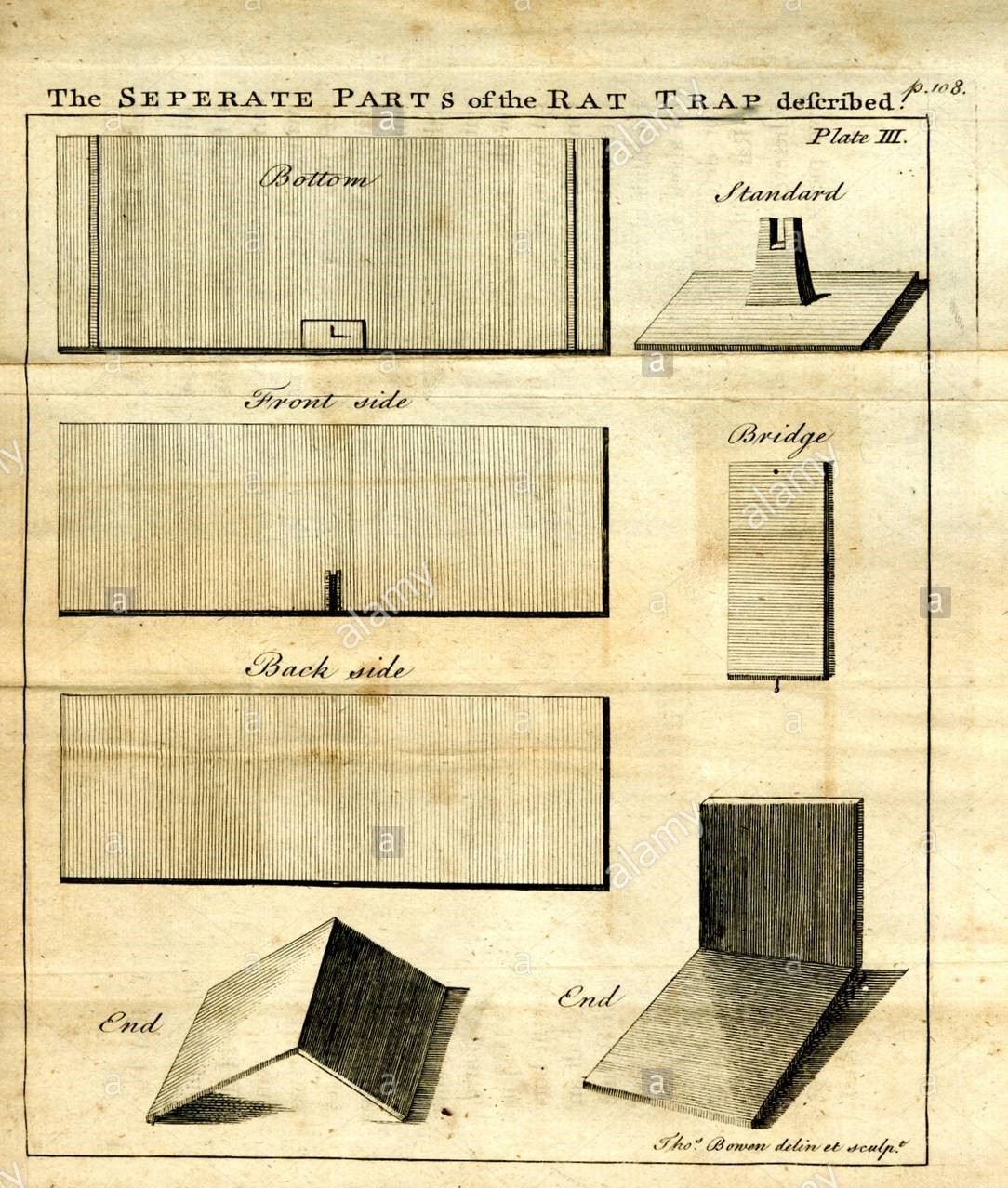

Prefabrikované lapače mrtvého pádu jsou vyráběny nezávisle na místě a době provozu. Základna a úderník jsou často desky. Jako mechanismus nastavení / uvolnění fungovala dřevěná tyč (západka) a nášlapná plocha. Leonard Mascall (1590) zaznamenal tento design jako „trapézový čtverec“ (obr. 3b). Ilustrace v rukopisech bajky Mashal ha-Kadmoni z let 1450–58 také ukazují tento design (Roth 1956, deska XIV b, c).

Starožitné vzorky z Tyrolska vykazují dvě varianty (obr. 3c): v levé je vzpřímený sloupek se šňůrkou se západkou přemístěn směrem dopředu; v pravém je nahrazen dvěma svislými sloupky a stropním nosníkem tvořícím rám. Osvětlení Mashal ha-Kadmoni z roku 1458 má také horní paprsek (Roth 1956, deska XIV d) a další starožitné vzorky přežily ve Skandinávii (Berg 1966). Lagercrantz (1984) uvádí více než 30 variant prefabrikovaných mrtvých pádů.

-----------------------------

Prefabricated dead fall arresters are manufactured independently of the place and time of operation. The base and striker are often plates. A wooden bar (latch) and a tread worked as the setting/release mechanism. Leonard Mascall (1590) recorded this design as a "trapezoidal square" (Fig. 3b). Illustrations in manuscripts of the Mashal ha-Kadmoni fable from 1450–58 also show this design (Roth 1956, plate XIV b, c).

Antique specimens from Tyrol show two variants (Fig. 3c): on the left, the upright post with the cord and latch is moved forward; on the right, it is replaced by two vertical posts and a ceiling beam forming the frame. The Mashal ha-Kadmoni illumination of 1458 also has an upper beam (Roth 1956, Plate XIV d), and other antique specimens survive in Scandinavia (Berg 1966). Lagercrantz (1984) lists more than 30 variations of prefabricated deadlifts.

Renesanční torzní pasti/Renaissance torsion traps:

Nazývat následující renesanční torzní pasti není jen časovou klasifikací, ale také naznačuje torzní pasti ze starověku (viz „Přímý příběh“ výše). Na obr. 4a rám rovněž drží zkroucenou šňůru napájející dřevěnou tyč, která tlačí na úderník. Mascall (1590) zaznamenal tento design jako „Následující trappe“, protože nazval prut lisující na horní desce „následující personál“. Proslavila se jako „past na myš Mérode“, protože pravé křídlo oltářního triptychu Mérode z doby kolem roku 1425 ukazuje takovou past na pracovním stole svatého Josefa (Web Gallery of Art 2010 poskytuje online obrázek s funkcí zvětšení). Zupnickovo (1966) zvědavé tvrzení, že dotyčný předmět je spíše tesařské letadlo než pasti na myši, bylo nepochybně vyvráceno (Berg 1966; Eisler 1966; Nickel 1966; Shapiro 1966; Drummond 1997a). Replika tesaře z Walker Art Gallery v Liverpoolu dokonce chytila myš (Jacob 1966).

V jiné renesanční torzní pasti sedí zkroucená šňůra na čepu a úderník je zasunut přímo do zkroucené šňůry (obr. 4b). Mascall (1590) zaznamenal tento design jako „Dragin trappe pro myši a ratty“. Dřevoryt mistra Caspera „Frau Venus und der Verliebte“ (asi 1485) ukazuje takovou past v levém horním rohu (dotisk s vysokým rozlišením v Niklu 1966) a ilustrace Mashal ha-Kadmoni z roku 1450 ukazuje dvojitou verzi (Roth 1956, deska XIVa). Mnoho starožitných vzorků, které tento design obměňovaly, přežilo jako „seversko-pobaltské“ torzní pasti (Lagercrantz 1964). Ačkoli většina má rám s lukem jako spodní protivník útočníkovi (viz obr. 4b), některé mají místo toho desku. „Uralo-sibiřské“ torzní pasti (viz Lagercrantz 1964) se liší v úderníku a mechanismu set / release, ale většina sdílí úklonu v základně, i když některé varianty se bez ní obejdou, protože spodní protivník jejich úderníku (klub s hroty) sedí na druhé straně základny a útočník se pohybuje o 180 stupňů. Luk v základně je pravděpodobně dědictvím mnohem starších pastí typu „clap-bow“ (viz výše), což naznačuje, že se luk přenesl spolu se zdrojem torzní energie. Tuto pasti lze považovat za hybrid s torzním zdrojem energie a úklonou v základně vycházející ze starodávných pastí na tleskání (obr. 2b), zatímco úderník a mechanismus set / release pocházejí z prefabrikovaných pastí pro mrtvý pád.

-----------------------------------------

Calling the following Renaissance torsion traps is not only a time classification, but also suggests torsion traps from antiquity (see "Straight Story" above). In Fig. 4a, the frame also holds a twisted cord feeding a wooden rod that pushes on the firing pin. Mascall (1590) recorded this design as "Following trappe" because he called the rod pressing on the top plate "following staff". It became famous as the "Mérode mousetrap" because the right wing of the Mérode altarpiece triptych from around 1425 shows such a trap on the workbench of Saint Joseph (Web Gallery of Art 2010 provides an online image with zoom function). Zupnick's (1966) curious claim that the object in question is a carpenter's plane rather than a mousetrap has been undoubtedly disproved (Berg 1966; Eisler 1966; Nickel 1966; Shapiro 1966; Drummond 1997a). A carpenter's replica from the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool even caught a mouse (Jacob 1966).

In another Renaissance torsion trap, a twisted line sits on a pin and the striker is inserted directly into the twisted line (Fig. 4b). Mascall (1590) recorded this design as "Dragin trappe for mice and ratts". Master Casper's woodcut "Frau Venus und der Verliebte" (c. 1485) shows such a trap in the upper left corner (high-resolution reprint in Nikl 1966), and the Mashal ha-Kadmoni illustration of 1450 shows a double version (Roth 1956, plate XIVa). Many antique specimens that varied this design survive as "Nordic-Baltic" torsion traps (Lagercrantz 1964). Although most have a frame with a bow as a lower opponent to the striker (see Fig. 4b), some have a plate instead. "Uralo-Siberian" torsion traps (see Lagercrantz 1964) differ in the striker and the set/release mechanism, but most share a bow at the base, although some variants do without it, as the lower opponent of their striker (the spiked club) sits on other side of the base and the hitter moves 180 degrees. The bow at the base is probably a legacy of much older "clap-bow" traps (see above), suggesting that the bow was carried over with the source of torsional energy. This trap can be considered a hybrid with the torsional power source and base bow derived from ancient clap traps (Fig. 2b), while the striker and set/release mechanism are derived from prefabricated dead drop traps.

Lapače s pružinou a úderníkem vyrobené z jednoho drátu - Úzkoúhlý/Catchers with spring and striker made of one wire - Narrow angle:

V „Dragin trappe with a great wyar“ (Mascall 1590; Crouch 1647; viz dodatek 1) je zakřivený, ale ne vinutý drát, jak úderník, tak pružina (obr. 5a). Pozdější varianty zvané „Planchette“ nebo „Assomoir grillagé“ měly drát se stočenými konci (obr. 5b). Historie církve poskytuje opět první záznam (Tanner 1694; Lagercrantz 1987). Ilustrace lze najít také v knize o tom, jak se vyhnout pastím sporu (Döhler 1723). Skeny obou výtisků jsou uvedeny v příloze 2 a příloze 3. Další varianta sklopila útočník se dvěma spojenými drátěnými tyčemi (obr. 5c). Ve viktoriánských vzorcích (obr. 5d) sloužil ohnutý drát jako zajišťovací tyč nesoucí funkce západky i struny. Varianty těchto vzorů byly patentovány později (např. Herbert 1877, 1881; Leibold 1879; Lewthwaite 1879; Rice 1879; Piggot 1898).

----------------------------

In "Dragin trappe with a great wyar" (Mascall 1590; Crouch 1647; see Appendix 1) there is a curved but not a coiled wire, both striker and spring (Fig. 5a). Later variants called "Planchette" or "Assomoir grillagé" had wire with coiled ends (Fig. 5b). Church history again provides the first record (Tanner 1694; Lagercrantz 1987). Illustrations can also be found in a book on how to avoid the pitfalls of contention (Döhler 1723). Scans of both prints are shown in Appendix 2 and Appendix 3. Another variant has the striker down with two connected wire rods (Fig. 5c). In Victorian patterns (Fig. 5d) the bent wire served as a locking bar carrying both latch and string functions. Variants of these designs were patented later (e.g. Herbert 1877, 1881; Leibold 1879; Lewthwaite 1879; Rice 1879; Piggot 1898).

Past ve tvaru L/L-shaped trap:

Sidney Earl (1877, 1879) z Corry a Horace Tinker (1882) z Meadville, PA, patentované pasti na krysy ve tvaru písmene L zadržující jednotku pružiny / úderníku (obr. 5e). Tvrdí pouze vylepšení, pravděpodobně na dřívějších pastích ve tvaru písmene L (např. Wright 1860). Henry Anderson (1890) z Whitesborough, TX, si nechal patentovat meziprodukt mezi L a plochým karabinou s pružinou / úderníkem (obr. 5f). Podobný design byl vyroben ve vesnici Neroth v německé oblasti Eifel (Drummond and Dagg 2010). Důvod neohýbání úderníku dozadu o 180 stupňů může spočívat v pružinách s příliš úzkým rozsahem pružné deformace, která riskuje plastickou deformaci.

---------------------------------

Sidney Earl (1877, 1879) of Corry and Horace Tinker (1882) of Meadville, PA, patented L-shaped rat traps retaining a spring/striker unit (Fig. 5e). Claims only an improvement, probably on earlier L-shaped traps (e.g. Wright 1860). Henry Anderson (1890) of Whitesborough, TX, patented an intermediate product between the L and the flat spring/firing carbine (Fig. 5f). A similar design was produced in the village of Neroth in the Eifel region of Germany (Drummond and Dagg 2010). The reason for not bending the firing pin back 180 degrees may lie in springs with too narrow a range of elastic deformation, which risks plastic deformation.

Plochá past/Flat trap:

V Hookerově (1894) konstrukci jeden drát stále tvoří pružinu i úderník, ačkoli pouze jeden konec je stočen a rovný konec prochází tunelem cívky.

-----------------------------

In Hooker's (1894) design, a single wire still forms both the spring and the striker, although only one end is coiled and the straight end passes through the coil tunnel.

Informace jsem čerpal z jisté americké webové stránky jejíž odkaz jsem stratil.

I got the information from a certain American website whose link I lost.