Cette earthcache vous fait découvrir un des joyaux de la ville d'Albi :

La Cathédrale Sainte Cécile

La cache vous fera tourner autour de ce monument.

This earthcache makes you discover one of the jewels of the city of Albi:

Sainte Cécile Cathedral

The cache will make you turn around this monument.

[FR]  [FR]

[FR]

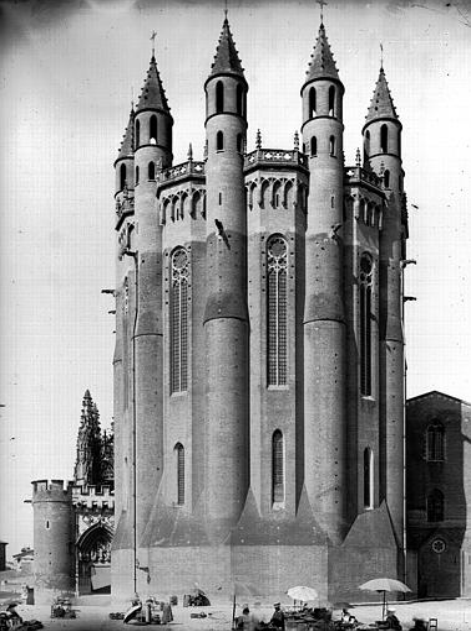

Cathédrale Sainte Cécile – 100% BRIQUE !

La cathédrale Sainte Cécile, inscrite en 2010 au patrimoine mondial de l'UNESCO et dont les tons ocres ont donné son surnom de ville rouge à Albi, est la plus grande cathédrale en brique au monde.

Visible de tous côtés à l’approche d’Albi, la cathédrale imposante par sa hauteur et la majesté de son clocher est comme un phare qui balise la route et invite à s’en rapprocher.

Église fortifiée, et à ce titre symbole du pouvoir temporel de l'Église, la cathédrale Sainte-Cécile exprime un renouveau catholique après la crise cathare. Chef-d’œuvre absolu du gothique méridional, architecture profondément originale, rigoureuse et austère, elle accueille un décor intérieur exceptionnel avec le plus grand « Jugement Dernier » du Moyen-Âge, et le plus vaste ensemble de peintures italiennes réalisées en France au début de la Renaissance.

Ce monument exceptionnel est donc construit en brique rouge cuite et pleine.

Essayons d’en savoir un peu plus sur la Brique !

Composant

Les briques utilisées à Albi sont élaborées à partir d’argile rouge.

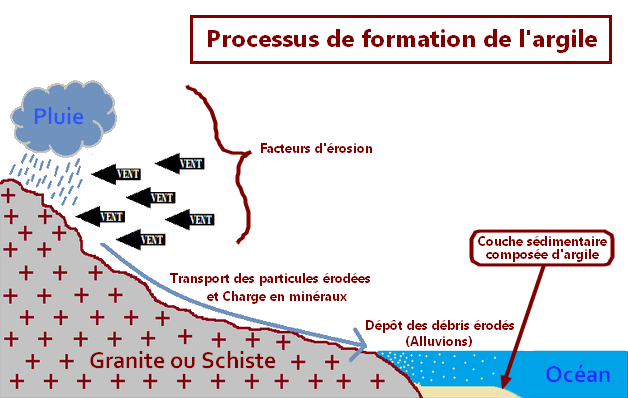

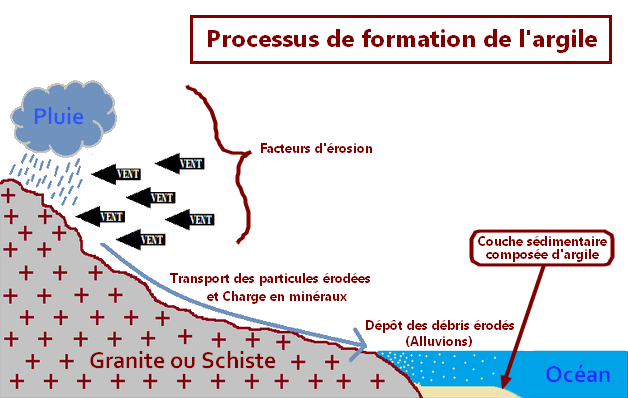

Au niveau géologique, les argiles désignent de très fines particules de matière arrachées aux roches par l'érosion. La plupart de ces particules proviennent de l'altération de roches silicatées : du granite (mica et feldspaths), du gneiss ou encore des schistes. Ces particules sont transportées par le vent ou l'eau sous forme de limon ou de vase. Les dépôts peuvent alors sédimenter et former une roche argileuse. Les affleurements argileux présentent une succession de strates empilées les unes sur les autres. C'est pour ces raisons qu'on les trouve systématiquement dans les sols et les formations superficielles.

Au niveau géologique, les argiles désignent de très fines particules de matière arrachées aux roches par l'érosion. La plupart de ces particules proviennent de l'altération de roches silicatées : du granite (mica et feldspaths), du gneiss ou encore des schistes. Ces particules sont transportées par le vent ou l'eau sous forme de limon ou de vase. Les dépôts peuvent alors sédimenter et former une roche argileuse. Les affleurements argileux présentent une succession de strates empilées les unes sur les autres. C'est pour ces raisons qu'on les trouve systématiquement dans les sols et les formations superficielles.

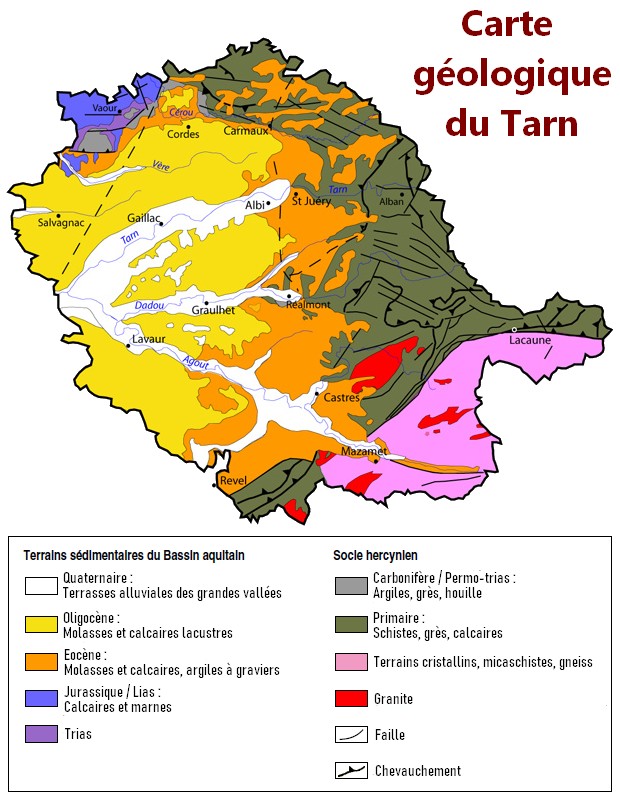

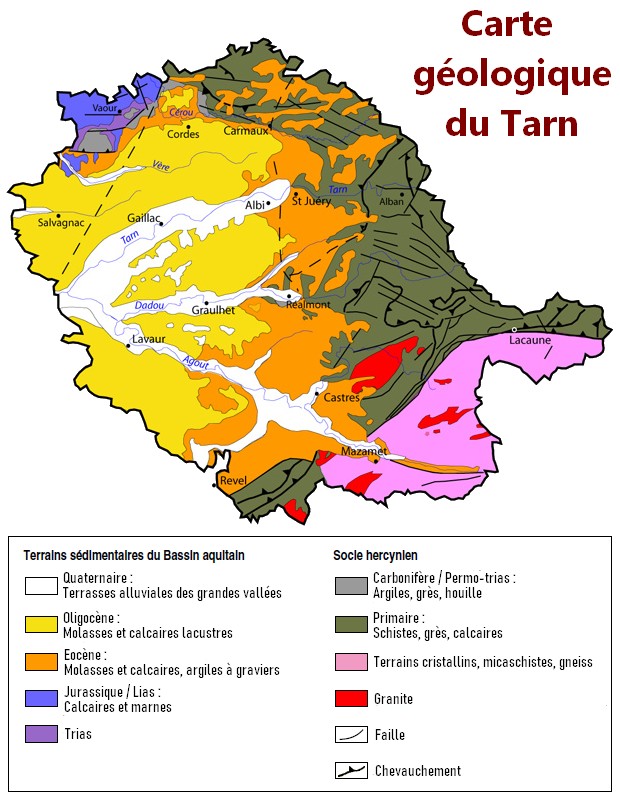

Dans le Tarn, la partie ouest où se trouve la ville d’Albi appartient à l’unité géologique du bassin aquitain. On y trouve donc des roches sédimentaires détritiques issues du démantèlement du relief de l'Est par l'érosion : molasses* et argiles à graviers.

Dans le Tarn, la partie ouest où se trouve la ville d’Albi appartient à l’unité géologique du bassin aquitain. On y trouve donc des roches sédimentaires détritiques issues du démantèlement du relief de l'Est par l'érosion : molasses* et argiles à graviers.

(*) : Pour en savoir plus sur les molasses, regardez la Earthcache de Jean-Paul CL sur la façade du Capitole de Toulouse (GC8HC47).

Les niveaux argileux des molasses tertiaires (Oligocène et Eocène moyen-supérieur) sont excessivement abondants dans la région d’Albi. Ce sont eux, notamment les « argiles à graviers », qui ont été autrefois intensément exploités dans la région d'Albi pour la fabrication de tuiles et de briques crues ou cuites. Des innombrables tuileries encore présentes au XIXème siècle, il ne restait plus, en 1983, que les exploitations situées à Marssac et Labastide de Lévis qui ne fournissaient plus qu'un très faible tonnage d'argile.

Dans son ‘’Explication de la carte géologique du Tarn » qu’il a publiée en 1848, Félix de Boucheporn explique que : « Les fours à briques et à tuiles sont en nombre considérable, principalement autour d'Albi et de Castres, et c'est encore le terrain tertiaire qui en fournit la terre argileuse. »

Fabrication

La brique n’a guère changé depuis l’Antiquité. Les Romains n’ont pas seulement légué aux artisans du Midi les grands formats des briques, les « foraines », ou la forme des tuiles en demi-tuyau et leur nom, les tegulae. Ils ont aussi laissé des savoir-faire et des types de fours encore utilisés tout au long du XIXème siècle dans tout le sud de la France.

1ère étape : extraction de la terre à la pioche et à la pelle.

2ème étape : préparation de la pâte : humidification de la terre, foulage au pied trois ou quatre fois de suite, « pourrissage » (décantation, phase de repos) dans les fosses puis malaxage et pétrissage à la main pour obtenir une pâte molle, homogène et plastique.

3ème étape : moulage dans un cadre de bois posé sur une planche sablée puis arrosage.

4ème étape : séchage quelques semaines sur une aire sablée sous des hangars à toiture basse, à l’abri du soleil, du vent et de la pluie.

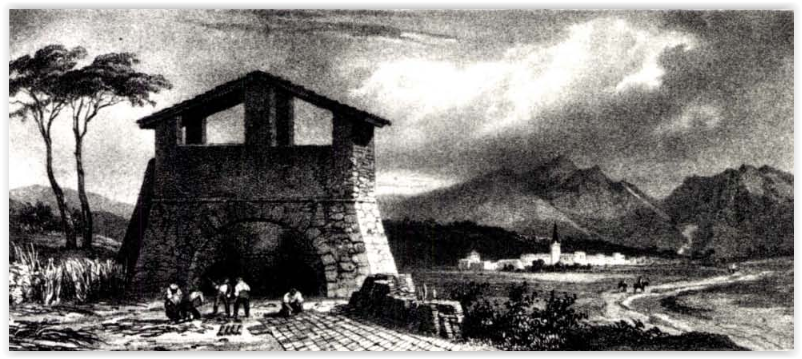

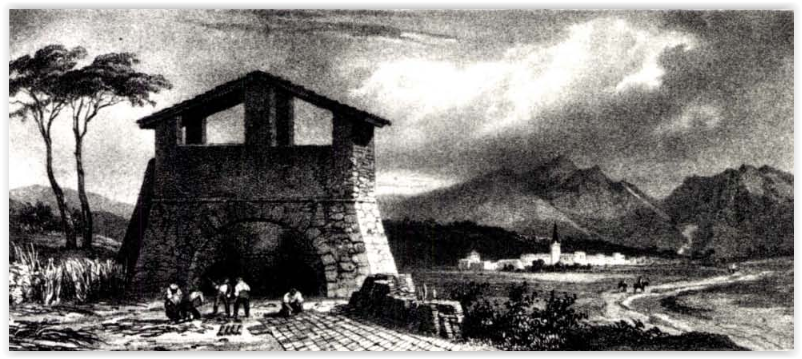

5ème étape : cuisson « à petit feu » (2 jours) puis « à grand feu » (3 jours) dans un four à parois verticales très épaisses (environ 6 m de haut et 3 m de large) – voir la geocache « Le four à briques ».

6èmeétape : refroidissement du four 2 à 3 jours, les briques étant défournées encore chaudes.

Four à briques des environs d'Alby vers 1830

Four à briques des environs d'Alby vers 1830Ce n’est qu’après la cuisson que les briques font voir leurs vraies couleurs. Elles présentent de grandes nuances, allant du rouge à Albi et Rabastens à un rose beaucoup plus pâle à Gaillac, Lavaur ou Giroussens et dans la région toulousaine. La teinte finale est fonction de la teneur en oxyde de fer de l’argile mais aussi du temps associé à la température de cuisson.

Histoire

Les premières briques cuites sont apparues en Mésopotamie vers le IIIème millénaire avant J.-C. puis se sont diffusées tout au long du pourtour de la méditerranée. Aux Ier et IIème siècles après J.-C., l’utilisation de la brique a pris un grand essor dans le monde romain qui s’est couvert d’édifices faits en briques cuites. Depuis le Moyen-Age jusqu'au XIXe siècle, la brique a constitué le matériau de construction de base à Albi. Seule l’époque romane a été marquée par l’utilisation de la pierre comme en témoigne encore la base du clocher, les murs latéraux et le cloître de la collégiale Saint-Salvi ou les vestiges de l’ancienne cathédrale romane.

Mur et cloître de la collégiale Saint-Salvi

L’usage de la brique à Albi tient aux conditions géologiques locales (l’argile y est abondante), et à la rareté des carrières de pierre (épuisement des gisements locaux). Les coûts engendrés par les transports en provenance des carrières plus éloignées expliquent l’abandon précoce de la pierre dès le début du XIIIème siècle. C’est ainsi qu’à Albi, le renouveau de la brique est daté d’entre 1220 et 1240. C’est à cette époque-là que survient le changement de matériaux clairement visible sur les murs de la collégiale Saint-Salvi.

Ce choix de la brique a également une raison liée à l’esprit du gothique mettant en valeur la pensée technique et la structure. L’architecture gothique était une recherche dans la décomposition des différentes fonctions techniques, donnant à voir les éléments porteurs : arcs, piliers, murs.

Il faut noter que l’évêque Bernard de Castanet, commanditaire de la construction de la cathédrale, était désireux de prouver que son choix était mieux adapté à la pauvreté prônée par les cathares (hérétiques opposés à son pouvoir religieux). De plus, l’adoption du ‘’gothique méridional’’ vient en opposition au choix du gothique classique pratiqué par les sympathisants du roi, lui qui voue une fidélité sans faille au Pape et entend ne dépendre que de lui.

Caractéristiques

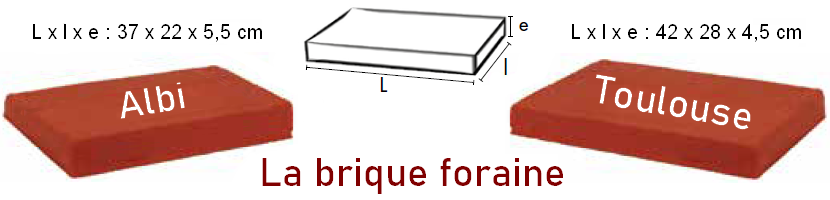

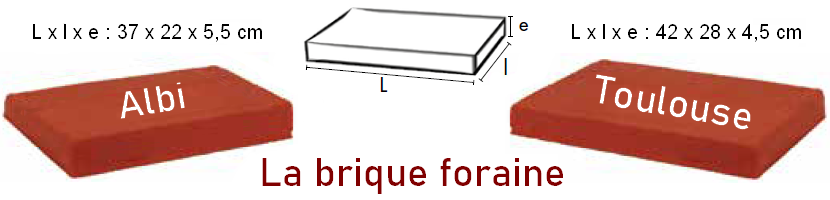

On trouve à Albi l’emploi d’un module particulier que l’on nomme « brique foraine ». Ce terme proviendrait du fait que la brique était cuite dans un four, et de meilleure qualité par opposition aux briques crues, ou bien du fait qu’on la vendait essentiellement dans les foires. Il existe aussi une hypothèse selon laquelle cette appellation proviendrait du latin foraneus « qui vient de l’extérieur », ces briques étant produites dans des briqueteries extérieures aux chantiers.

Le module albigeois semble spécifique puisque de dimension différente à celle que l’on trouve dans le reste du Midi toulousain. La brique foraine albigeoise mesure 37 x 22 x 5,5 cm alors que le format toulousain est 42 x 28 x 4, 5 cm.

La brique foraine répond à un module harmonieux, facilement manipulable (de 8 à 9 kg), de plus, ses dimensions moyennes (37 x 22 x 5,5 cm) en font un module approchant du nombre d’or (environ 1,618) correspondant à une recherche d’équilibre des proportions. La brique foraine a une surface de portance très importante, qui permet de monter des maçonneries complètes en se passant de tout élément de chaînage en pierre.

Cet aspect technique vient s’ajouter aux critères économique, religieux et politiques déjà cités. Et c’est ainsi que le gothique méridional et l’usage de la brique vont s’imposer à Albi.

Voilà ! Maintenant que vous savez presque tout sur la brique et son utilisation à Albi, il ne reste plus qu’à visiter la cathédrale Sainte-Cécile et même la cité épiscopale dans son ensemble. Mais prévoyez beaucoup de temps tant il y a de choses à voir …

Parmi tous les sites traitant de la cathédrale Sainte-Cécile, le site www.cite-episcopale-albi.fr présente l’avantage d’être très complet. Une visite de ce site complètera à merveille vos connaissances et vous donnera sûrement envie de voir des choses supplémentaires.

J'espère que vous prendrez autant de plaisir à faire cette earthcache que j'en ai eu grâce aux recherches documentaires pour la concevoir.

Sources :

http://www.cite-episcopale-albi.fr - https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki - http://www.toulouse-brique.com - https://asnat.fr - https://www.geowiki.fr - https://www.mairie-albi.fr

La Earthcache

PARTIE 1 : Pour valider cette Earthcache, vous devrez tout d'abord répondre aux questions suivantes tirées du texte :

1a) Quel est l'élément chimique qui est responsable de la coloration des briques ?

1b) Pour un même site d'extraction de l'argile, quel facteur peut faire changer la couleur des briques ?

1c) Où trouve-t-on la même couleur de briques qu'à Albi ?

2a) De quelles époques géologiques datent les gisements d'argile utilisés pour confectionner les briques d'Albi ?

2b) Quelles sont les roches qui ont été altérées pour permettre ensuite le dépôt de sédiments argileux ?

3a) Quel est le nom du module spécifique de brique utilisé dans le Midi toulousain ?

3b) Quelle est la différence entre celui qui était utilisé à Toulouse et celui employé à Albi ?

4) A quelle date l'emploi de la Pierre a-t-il fait place à celui de la Brique ?

PARTIE 2 : Je vous propose maintenant de tourner tout autour de la cathédrale et d'observer plus particulièrement à deux endroits.

Question 5 (N 43°55.720' - E 002°08.560') :

A cet endroit, vous aurez l'occasion d'observer plusieurs endroits où différentes campagnes de réfection sont bien visibles. On peut constater l'utilisation de briques industrielles reconnaissables à leur aspect beaucoup plus lisse. Certains briques violacées (signe d'une cuisson plus forte) ont également été employées. Enfin, certaines briques montrent des traces de layage. L'aspect strié de la brique est dû à l'utilisation d'une laye, sorte de marteau à bords tranchants utilisé après la pose pour égaliser la surface extérieure.

5) Prenez une photo d'un seul de ces trois aspects de brique aux coordonnées exactes indiquées (avec un objet personnel ou en mode "selfie", c'est encore mieux) et joignez-la à vos réponses.

Question 6 (N 43°55.706' - E 002°08.629') :

6) Qu'est-ce qui explique le changement de couleurs de briques que l'on peut observer au dessus du niveau des gargouilles ? A quel homme le doit-on ?

PARTIE 3 (OPTIONNELLE) : Prenez une photo de vous, de votre GPS ou d'un objet personnel devant la cathédrale Sainte Cécile d'Albi. Votre imagination dans le cadrage sera la bienvenue !

Loguez cette cache "Found It" et envoyez-moi vos propositions de réponses soit via mon profil, soit via la messagerie geocaching.com (Message Center), et je vous contacterai en cas de problème.

Complément de visite

Etape 1 (N 43°55.712' - E 002°08.502') :

Depuis cette étape, vous pouvez mieux voir ces trous répartis uniformément sur la façade qui sont plus particulièrement visibles ici, au niveau du clocher. Ces trous s'appellent des trous de boulins. Ils ont servi à fixer les traverses en bois qui supportaient les planchers d'échafaudage (platelages).

Etape 2 (N 43°55.741' - E 002°08.503') :

Vous vous trouvez ici à côté des vestiges du cloître de la cathédrale romane qui démontrent qu'à cette époque la pierre était utilisée.

Etape 3 (N 43°55.729' - E 002°08.581') :

Cette porte "basse" de la sacristie porte la date de 1883. C'est à cette époque qu'ont été menés les ultimes travaux au niveau de la sacristie. Cela correspond au moment où on a détruit les maisons qui s'appuyaient au secteur nord du chevet de la cathédrale et à la sacristie.

Etape 4 (N 43°55.686' - E 002°08.559') :

Sur la photo de gauche du panneau d'information, on aperçoit encore des maisons qui jouxtent les murs de la cathédrale et qui ont été rasées à la fin du XIXème siècle.

Si vous êtes passé par le "baldaquin" en pierre (oui, oui, il y en a aussi !) et avez observé Castor et Pollux, les deux cadrans solaires jumeaux, votre petit tour extérieur est maintenant terminé mais il y a encore beaucoup de choses à découvrir ...

N'hésitez pas à rentrer dans la cathédrale où vous pourrez voir les riches décorations intérieures, les fresques et peintures murales, les voûtes peintes, la scène du Jugement Dernier, les trompe-l’oeil, le jubé de style gothique flamboyant et l'orgue gothique du XVIème Siècle, sans oublier le Trésor.

ATTENTION ! Seule la visite de la nef est gratuite, les accès au choeur (jubé) et au Trésor sont payants.

HORAIRES : 9h00 - 18h30 (18h00 le dimanche)

[EN]  [EN]

[EN]

Sainte Cécile Cathedral - 100% BRICK!

The Sainte Cécile cathedral, listed in 2010 as a UNESCO world heritage site and whose ocher tones gave its nickname of red city to Albi, is the largest brick cathedral in the world.

Visible from all sides as you approach Albi, the imposing cathedral by its height and the majesty of its bell tower is like a beacon that marks the road and invites you to get closer.

Fortified church, and as a symbol of the temporal power of the Church, the Sainte-Cécile cathedral expresses a Catholic renewal after the Cathar crisis. Absolute masterpiece of southern Gothic, deeply original, rigorous and austere architecture, it hosts an exceptional interior decor with the largest “Last Judgment” of the Middle Ages, and the largest set of Italian paintings made in France at the beginning of the Renaissance.

This exceptional monument is built in brick red terracotta and full.

Let's try to know a little more about the Brick!

Component

The bricks used in Albi are made from red clay.

At the geological level, clays designate very fine particles of material torn from rocks by erosion. Most of these particles come from the weathering of silicate rocks: granite (mica and feldspar), gneiss or even shales. These particles are transported by wind or water in the form of silt or mud. The deposits can then sediment and form a clay rock. The clay outcrops have a succession of strata stacked on top of each other. It is for these reasons that they are systematically found in soils and surface formations.

In the Tarn, the western part where the town of Albi is located belongs to the geological unit of the Aquitaine basin. There are therefore detrital sedimentary rocks from the dismantling of the East relief by erosion: molasses* and gravelly clays.

(*) : to find out more about the molasses, look at Jean-Paul CL's Earthcache on the facade of the Capitole of Toulouse(GC8HC47).

The clay levels of tertiary molasses (Oligocene and Middle-Upper Eocene) are excessively abundant in the Albi region. It is them, in particular the “gravel clays”, which were formerly intensively exploited in the region of Albi for the manufacture of tiles and raw or cooked bricks. Of the innumerable tile factories present in 19th century, there remained only, in 1983, the exploitations located in Marssac and Labastide de Lévis which only provided a very small tonnage of clay.d'argile.

In his "Explanation of the geological map of the Tarn" which he published in 1848, Félix de Boucheporn explains that : « Brick and tile ovens are in considerable numbers, mainly around Albi and castres, and it' still the tertiary land wich provides the clay soil. »

Manufacturing

Brick has hardly changed since Antiquity. The Romans did not only bequeath to the artisans of the South the large formats of bricks, the "fairgrounds", or the shape of the half-pipe tiles and their name, the tegulae. They also left know-how and types of ovens still used throughout the 19th century throughout the south of France.

1st step: extraction of the earth with picks and shovels.

2nd step: preparation of the dough: moistening the soil, treading with the foot three or four times in a row, " rotting " (decantation, resting phase) in the pits then mixing and kneading by hand to obtain a soft dough, homogeneous and plastic.

3rd step: molding in a raised wooden frame on a sandblasted plate then watering.

4th step: drying few weeks on a sandy area under the low roof sheds, sheltered from the sun, wind and rain.

5th step: cooking "slowly" (2 days) then "over high heat" (3 days) in an oven with very thick vertical walls (about 6 m high and 3 m wide) - see geocache « Le four à briques ».

6thstep: cooling the oven 2 to 3 days, the bricks being kiln still hot.

Brick oven near Alby around 1830

Brick oven near Alby around 1830It is only after firing that the bricks show their true colors. They have great nuances, ranging from red in Albi and Rabastens to a much lighter pink in Gaillac, Lavaur or Giroussens and in the Toulouse region. The final color depends on the iron oxide content of the clay but also on the time and the firing temperature.

History

The first fired bricks appeared in Mesopotamia in the 3rd millennium BC then spread throughout the Mediterranean region. In the 1st and 2nd centuries AD, the use of bricks took off in the Roman world which was covered with buildings made of baked bricks. From the Middle Ages to the 19th century, brick was the basic building material in Albi. Only the Romanesque era was marked by the use of stone as evidenced by the base of the bell tower, the side walls and the cloister of the Saint-Salvi collegiate church or the remains of the old Romanesque cathedral.

Wall and cloister of the Saint-Salvi collegiate church

The use of brick in Albi takes local geological conditions (the clay there is abundant), and the scarcity of stone quarries (sources exhausted local). The costs generated by transport from more distant quarries explain the early abandonment of the stone from the beginning of the 13th century. Thus, at Albi, the revival of the brick is dated between 1220 and 1240. It was at this time that the change of materials occurred - clearly visible on the walls of Saint-Salvi collegiate.

This choice of brick also has a reason linked to the spirit of Gothic highlighting technical thought and structure. Gothic architecture was a research into the decomposition of the different technical functions, showing the supporting elements: arches, pillars, walls.

Note that bishop Bernard de Castanet, sponsor the construction of the cathedral, was eager to prove that his choice was better suited to poverty advocated by the Cathars (heretics opposed to his religious authority). In addition, the adoption of "southern Gothic" came in opposition to the choice of classical Gothic practiced by the king's sympathizers, him who dedicates an unfailing loyalty to the Pope and intends to depend only on him.

Features

We find in Albi the use of a particular module that we call "fairground brick". This term comes from the fact that the brick was baked in an oven, and of better quality as opposed to raw bricks, or else from the fact that it was sold mainly at fairs. There is also a hypothesis according to which this name comes from the Latin foraneus "which comes from the outside", these bricks being produced in brickyards outside construction sites.

The Albigensian module seems specific since it is different in size from that found in the rest of the Midi region of Toulouse. The Albigensian fairground brick measures 37 x 22 x 5.5 cm while the Toulouse format is 42 x 28 x 4.5 cm.

The fairground brick responds to a harmonious module, easily manipulated (from 8 to 9 kg), in addition, its average dimensions (37 x 22 x 5.5 cm) make it a module approaching the corresponding golden ratio (around 1.618) looking for a balance of proportions. The fairground brick has a very large bearing surface, which makes it possible to mount complete masonry without any stone chaining element.

This technical aspect is in addition to the economic, religious and political criteria already mentioned. And this is how Southern Gothic and the use of brick will impose themselves on Albi.

Here! Now that you know almost everything about brick and its use in Albi, it only remains to visit the Sainte-Cécile cathedral and even the episcopal city as a whole. But allow plenty of time because there is so much to see ...

Among all the sites dealing with Sainte-Cécile cathedral, the site www.cite-episcopale-albi.fr has the advantage of being very complete. A visit to this site will perfectly complement your knowledge and will surely make you want to see additional things.

I hope you will take as much pleasure in making this eartcache as I had thanks to the documentary research to design it.

Sources :

http://www.cite-episcopale-albi.fr - https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki - http://www.toulouse-brique.com - https://asnat.fr - https://www.geowiki.fr - https://www.mairie-albi.fr

The Earthcache

PART 1 : To validate this Earthcache, you must first answer the following questions taken from the text:

1a) What is the chemical element that is responsible for coloring bricks?

1b) What factor can change the color of bricks for the same clay extraction site?

1c) Wher do you find the same color of bricks as in Albi?

2a) Which geological eras date the clay deposits used to make the bricks of Albi?

2b) Which rocks have been altered to allow the deposition of clay sediments?

3a) What is the name of the specific module used in the Midi region of Toulouse?

3b) What is the difference between the one used in Toulouse and the one used in Albi?

4) On what date did the use of stone give way to that of brick?

PART 2 : I now suggest that you turn around the cathedral and observe more particularly in two places.

Question 5 (N 43°55.720' - E 002°08.560') :

At this location, you will have the opportunity to observe several locations where different repair campaigns are clearly visible. We can see the use of industrial bricks recognizable by their much smoother appearance. Certain purplish bricks (a sign of stronger baking) were also used. Finally, some bricks show traces of "layage". The striated appearence of the brick is due to the use of a "laye", a kind of hammer with sharp edges used after laying to equalize the exterior surface.

5) Take a picture of just one of these three brick aspects at the exact coordinates indicated (with a personnal object or in "selfie" mode, even better) and attach it to your answers.

Question 6 (N 43°55.706' - E 002°08.629') :

6) What explains the change in brick colors that can be observed above the level of the gargoyles? To which man do we owe it?

PART 3 (OPTIONNAL): Take a photo of yourself, your GPS or a personal object in front of the Sainte Cécile cathedral of Albi. Your imagination in framing will be welcome!

Log this cache as "Found It" and send me your response suggestions either via my profile or via the geocaching.com messaging (Message Center), and I will contact you in case of problems.

Complement of visit

Step 1 (N 43°55.712' - E 002°08.502') :

From this stage, you can better see these holes distributed uniformely on the facade which are more particularly visible here, at the level of the bell tower. These holes are called "boulins" holes. They were used to fix the wooden sleepers that supported the scaffolding floors.

Step 2 (N 43°55.741' - E 002°08.503') :

You are here next to the remains of the cloister of the Romanesque cathedral which demonstrate that stone was used at that time.

Step 3 (N 43°55.729' - E 002°08.581') :

This "low" door of the sacristy bears the date of 1883. It was at this time that the last work were carried out at the level of the sacristy. This corresponds to the time when the houses that were built on the northern sector of the cathedral chevet and the sacristy were destroyed.

Step 4 (N 43°55.686' - E 002°08.559') :

In the photo on the left of the information panel, you can still see houses which adjoin the walls of the cathedral and which were razed at the end of the 19th century.

If you went through the stone "canopy" (yes, yes, there are stones too!) and observed Castor and Pollux, the two twin sundials, your little outside tour is now over but there are still a lot of things to discover ...

Do not hesitate to enter the cathedral where you will be able to see the rich interior decorations, the frescoes and murals, the painted vaults, the scene of the Last Judgement, the trompe-l'oeil, the rood screen of flamboyant Gothic style and the Gothic organ from the XVIth Century, whitout forgetting the Treasury.

WARNING ! Only the visit to the nave is free, access to the choir (rood screen) and the Treasury are chargeable.

TIMETABLE: 9 a.m. - 6.30 p.m. (6 p.m. Sunday)