Le contexte

Au cœur des Grandes Alpes, venez découvrir la richesse géologique d’une rando sans difficulté particulière (environ 10 km pour 650m de dénivelé positif), avec un point de vue magique sur le Mont-Blanc au col de la Seigne !

La formation des Alpes

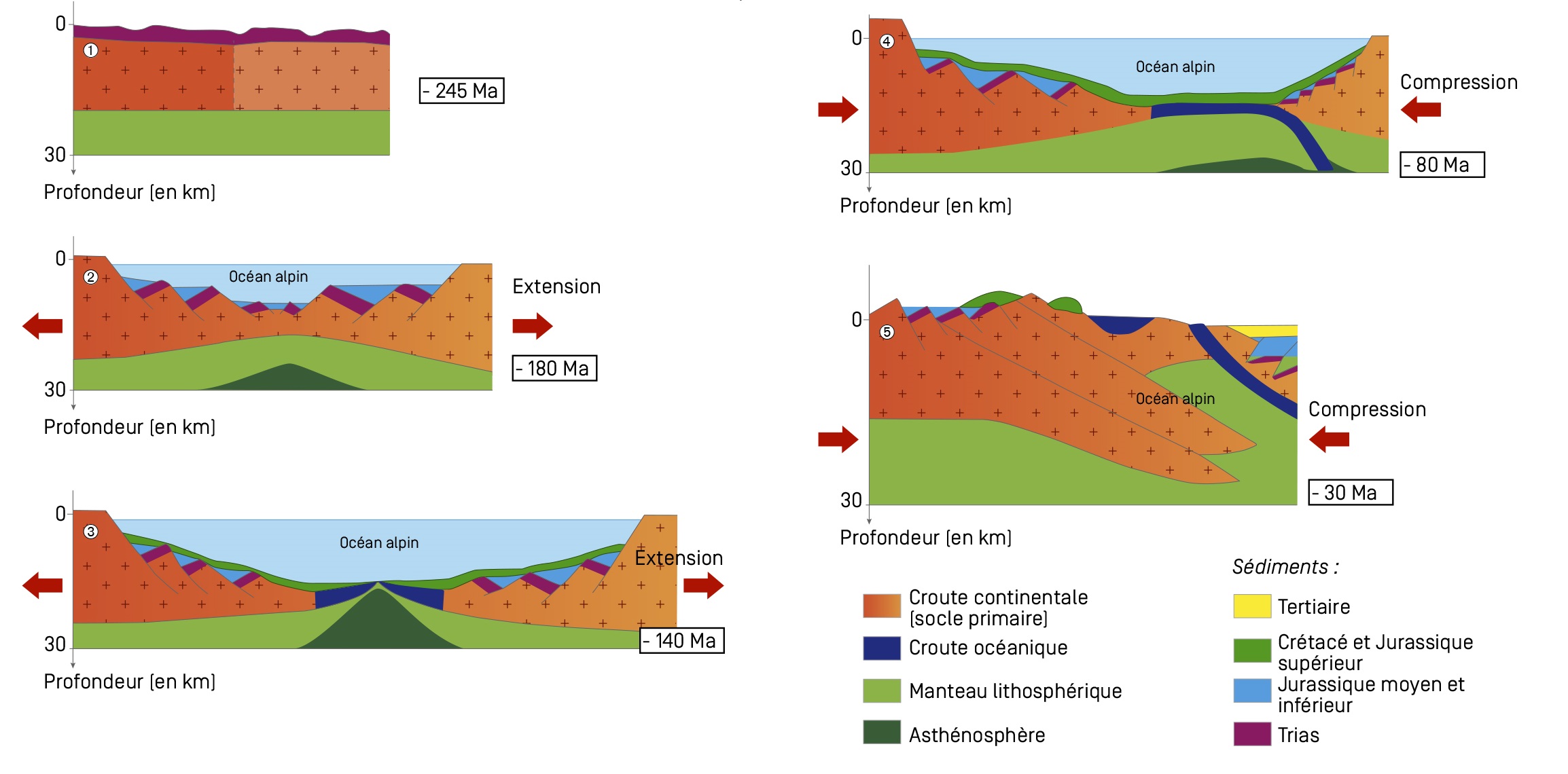

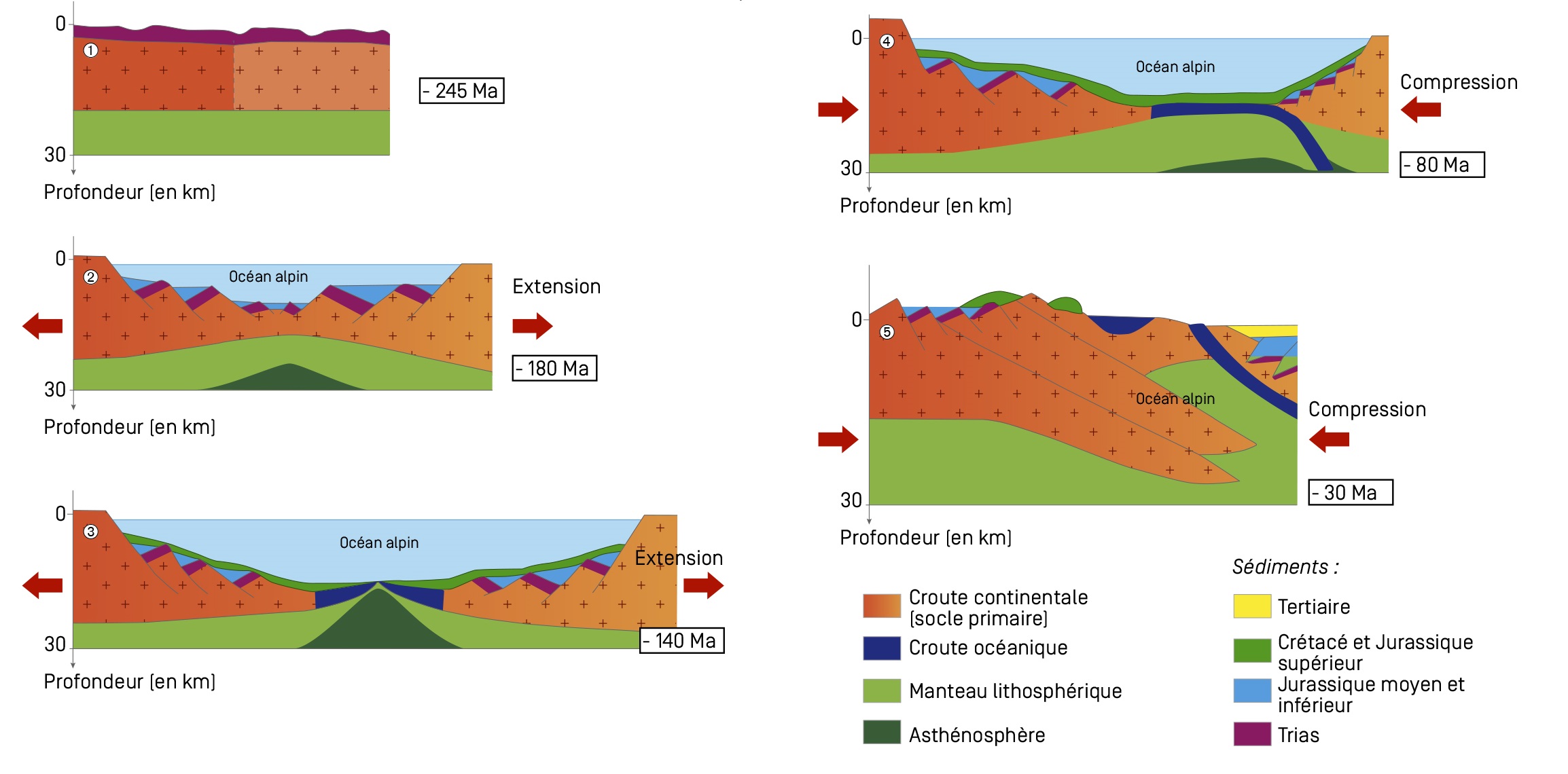

La croûte terrestre est morcelée en plaques qui se déplacent les unes par rapport aux autres. Cette tectonique des plaques est à l’origine de la genèse des océans et des chaines de montagnes comme les Alpes.

Au Paléozoïque (-542 à -251 millions d'années), les continents sont regroupés en un seul super-continent, la Pangée, qui commence à se morceler à la fin du Trias (-220 Ma). La grande chaîne hercynienne (chaîne varisque) qui occupait la Gallice, la Bretagne, le Massif Central, la partie Ouest des Alpes, les Vosges, l’Allemagne et au-delà, s’est effondrée, érodée. La région des Alpes est alors continentale et relativement plate, et ce qui reste de la chaîne hercynienne constitue le socle cristallin de la région.

Lors du Jurassique inférieur (- 200 à - 176 Ma), la plaque européenne s’étire et se morcèle. Un affaissement (rift) se produit et permet une expansion océanique. C’est la naissance de l’Océan Alpin. Au stade précoce, le rift met en place une mer étroite, peu profonde et mal alimentée en eau, comme la Mer Rouge actuelle. Les dépôts sédimentaires s’accumulent et formeront plus tard des roches calcaires et/ou argileuses. En bordure du domaine océanique, le domaine continental est affecté par des failles, de grandes cassures qui le débitent en morceaux. Au Crétacé Inférieur (-145 à -100 Ma), l’Océan Alpin a atteint sa largeur maximale, estimée à 1000 km environ.

Au Crétacé Supérieur (-100 à -65 Ma), la fermeture de l’Océan Alpin s’amorce et l’orogénèse alpine débute : la plaque africaine amorce un mouvement de rotation. Les plaques européenne et africaine entrent alors dans une collision par subduction : la croûte océanique s’enfonce sous la croûte continentale. Outre le fait qu’elle entraîne une disparition de cette croûte océanique, la subduction provoque le plissement et parfois le métamorphisme des roches situées au voisinage du plan de friction, les plus affectées étant les roches sédimentaires.

À partir de l’Éocène (-56 Ma), l’Océan Alpin s’est complètement refermé et la collision des plaques a entraîné une surélévation des parties frontales de ces dernières. Plusieurs épisodes de compressions poursuivent l’orogénèse ainsi que le métamorphisme des roches, soumises à des contraintes gigantesques. Ce carambolage continue de nos jours : en effet, les Alpes continuent de s’élever de 20cm environ par siècle. Aujourd’hui, la lecture des paysages permet de repérer ces différentes couches de roches d’âge très différents, déformées, effondrées, plissées, transformées et en cours d’érosion.

Les roches du massif

Si l’on retrouve dans les Alpes un grand nombre de roches (granite, gneiss, calcaires, dolomies, brèches, ophiolites, marbres, schistes, flyschs, …), vous avez face à vous un échantillonnage très intéressant :

- calcaire finement plaquetté : roche à patine gris clair, donnant en éboulis des plaquettes sonores. Formation : -150Ma ;

- schiste métamorphique argileux : roche formée d'argile ayant sédimenté au fond d'une eau calme et peu profonde. Sa haute teneur en fer et en magnésium lui confère une couleur presque noire et ils présentent souvent un aspect lustré, brillant. Formation : -130 Ma ;

- calcaire marmoréen (marbre) : roche montrant une fine zonation alternativement grise et blanche. La patine d'ensemble très claire fait ressortir tout particulièrement ce niveau, au bord duquel on retrouve une alternance de bancs de calcaires cristallins fins, à patine jaunâtre, formant des strates assez mal individualisées séparées par des interstrates plus sombres. Formation : -200 Ma ;

- gneiss et micaschiste : socle cristallin, roche métamorphique formée lors de la formation de la chaîne hercynienne. Ici, ces roches constituent les plus hauts sommets. Formation : -300 Ma ;

- calcaire massif : leur patine jaune se voit de loin. Formation : - 190 Ma.

Les plis

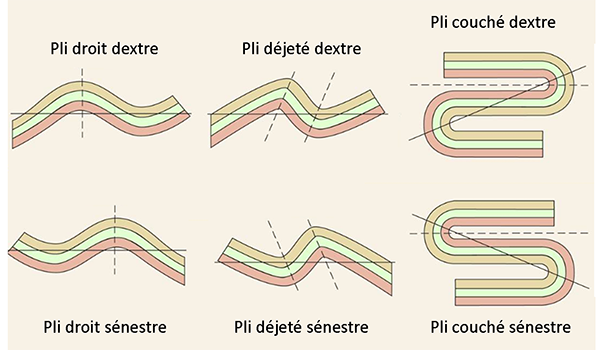

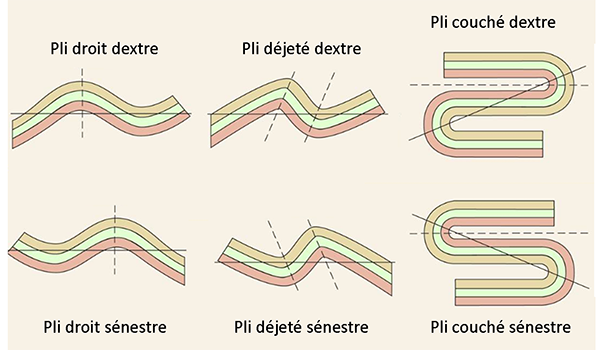

Un pli est une déformation des roches sous l'effet des contraintes. La roche, sous l'effet des forces tectoniques, n'a pas cassé mais plié. Ce comportement "plastique" peut être celui de roches très rigides, d'habitude cassantes. En effet, l'application sur une longue période de forces de faible intensité permet une modification graduelle de la roche (son plissement) au lieu de sa fracturation. On distingue plusieurs types de plis (voir schéma) selon la géométrie, dont :

- les plis droits : les deux flancs du pli ont le même pendage mais de sens opposé, il existe un plan axial de symétrie ;

- les plis déjetés : on trouve un plan axial légèrement incliné de tel manière que les deux flans ont un pendage différent ;

- les plis couchés : le plan axial est presque horizontal, et les flancs sont horizontaux et se recouvrent.

Selon le « sens » du pli, on peut également distinguer les plis sénestres des plis dextres. Pour les reconnaître, c’est simple : le pli sénestre dessine la lettre S, et le pli dextre est son image dans un miroir (voir schéma) :

Bibliographie / sitographie

Antoine et al., Géologie alpine, 51, 1975, 5-23

https://www.emse.fr/~bouchardon/enseignement/processus-naturels/up1/web/wiki/Q%20-%20Tectonique%20-%20La%20formation%20de%20la%20chaine%20de%20montagnes%20%20Alpes%20-%20Martin.htm

http://geologie-alpe-huez.1001photos.com/roches/ocean.php

http://www.reseau-canope.fr/svt-taches-complexes/chapitre.html?page=tt1st2c2ua

https://ft.univ-tlemcen.dz/assets/uploads/pdf/departement/gc/houti/Chapitre-4-NOTION-SUR-LA-TECTONIQUE.pdf

https://docplayer.fr/8422905-Les-plis-partie-1-geometrie-et-representation-stereographique.html

Questions

La lecture attentive du descriptif de la cache, ainsi qu'une observation des éléments de terrain et un peu de déduction sont normalement suffisants pour répondre aux questions de cette EarthCache.

Depuis les coordonnées du listing, observez la crête au premier plan à l’Ouest, de l’autre côté de la vallée des Glaciers, et répondez aux questions suivantes :

1. À l’aide du descriptif, attribuez chacune des zones A, B, C, D et E (voir photo « Zones ») aux différentes roches décrites.

2. En vous aidant de l’échelle des temps géologiques, préciser la période et l’époque géologiques de la formation des roches de chacune de ces zones (exemple : Dévonien moyen).

3. D’après la chronologie décrite, quelles sont les zones correspondant à des roches formées à partir de dépôts sédimentaires océaniques ?

4. Le passé le plus récent se trouve-t-il plutôt en zone A ou en zone E ? Pourquoi cela peut-il paraître surprenant ?

5. D’après l’échelle des temps (image « Echelle des temps »), combien de millions d’années d’histoire de la formation des roches avez-vous sous les yeux avec ces 5 zones ?

6. Observez mieux la zone D ( Grande Écaille, voir photo « Zone D »). Vous y verrez un témoignage des contraintes tectoniques subies par les roches lors de la formation des Alpes. Déterminer le type de pli (droit, déjeté ou couché) et son orientation (dextre ou sénestre) ?

Optionnel : une photo de vous ou votre GPS sur place n’est pas obligatoire mais fortement appréciée ^^

Vous pouvez vous loguer sans attendre notre confirmation, mais

vous devez nous envoyer les réponses en même temps soit par mail via notre profil, soit via la messagerie geocaching.com (Message Center). S'il y a des problèmes avec vos réponses nous vous en ferons part.

Les logs enregistrés sans réponses seront supprimés.

The context

In the heart of Great Alps, come and discover the geological richness of a hike without any particular difficulty (about 10 km for 650m of positive altitude difference), with a sublime viewpoint on Mont-Blanc at the Col de la Seigne!

Alps formation

The earth's crust is divided into plates that move relative to each other. This plate tectonics is at the origin of the genesis of oceans and mountain ranges such as the Alps.

In the Paleozoic (-542 to -251 million years ago), the continents were grouped into a single super-continent, Pangaea, which began to break up at the end of the Triassic Period (-220 Ma). The great Hercynian chain (Variscan chain) that occupied Gallicia, Brittany, the Massif Central, the western part of the Alps, the Vosges, Germany and beyond, has collapsed and eroded. The Alps region was continental and relatively flat, and what remained of the hercynian chain formed the crystalline base of the region.

During the Lower Jurassic (-200 to -176 Ma), the European plate stretches and splits. A rift occurs and allows oceanic expansion. It is the birth of the Alpine Ocean. At the early stage, the rift creates a narrow, shallow and poorly supplied sea, like the current Red Sea. Sedimentary deposits accumulate and will later form limestone and/or clayey rocks. On the edge of the oceanic domain, the continental domain is affected by faults, large breaks that cut it into pieces. At the Lower Cretaceous (-145 to -100 Ma), the Alpine Ocean reached its maximum width, estimated at about 1000 km.

In the Upper Cretaceous (-100 to -65 Ma), the closure of the Alpine Ocean begins and alpine orogenesis begins: the African plate begins a rotational movement. The European and African plates then enter a subduction collision: the oceanic crust sinks under the continental crust. In addition to causing the disappearance of this oceanic crust, subduction causes the folding and sometimes metamorphism of rocks located in the vicinity of the friction plane, the most affected being sedimentary rocks.

From the Eocene (-56 Ma) onwards, the Alpine Ocean closed completely and the collision of the plates raised the frontal parts of the plates. Several episodes of compression continue the orogenesis and metamorphism of the rocks, which are subjected to gigantic stresses. Today, reading the landscapes makes it possible to identify these different layers of rocks of very different ages, deformed, collapsed, folded, transformed and eroding.

Massif rocks

If there are a large number of rocks in the Alps (granite, gneiss, limestone, dolomite, breccia, ophiolite, marble, schist, flyschs,...), you have before you a very interesting sample:

- finely plastered limestone: rock with a light grey patina, giving scree to sound plates. Formation: -150Ma ;

- clayey metamorphic shale: rock formed by clay that has sedimented on the bottom of calm, shallow water. Its high iron and magnesium content gives it an almost black colour and they often have a glossy, shiny appearance. Formation: -130 Ma ;

- marble limestone (marble): rock showing a fine zonation alternately grey and white. The very light overall patina particularly highlights this level, at the edge of which there is an alternation of banks of fine crystalline limestone, with a yellowish patina, forming rather poorly individualized strata separated by darker interstrates. Formation: -200 Ma ;

- gneiss and micaschist: crystalline basement, metamorphic rock formed during the formation of the hercynian chain. Here, these rocks are the highest peaks. Formation: -300 Ma ;

- massive limestone: their yellow patina can be seen from afar. Formation: - 190 Ma.

Folds

A fold is a deformation of rocks under the effect of stress. The rock, under the influence of tectonic forces, did not break but bent. This "plastic" behaviour can be that of very rigid, usually brittle rocks. Indeed, the application of low intensity forces over a long period of time allows a gradual modification of the rock (its folding) instead of its fracturing. There are several types of folds (see diagram) depending on the geometry, including:

- straight folds: the two sides of the fold have the same dip but in opposite directions, there is an axial plane of symmetry ;

- depressed folds: there is a slightly inclined axial plane so that the two blanks have a different dip;

- lying folds: the axial plane is almost horizontal, and the flanks are horizontal and overlapping.

Depending on the "direction" of the fold, we can also distinguish between senestral folds and dextral folds. To recognize them, it's simple: the senestral fold draws the letter S, and the dexterous fold is its image in a mirror (see diagram):

Bibliography / sitography

Antoine et al., Géologie alpine, 51, 1975, 5-23

https://www.emse.fr/~bouchardon/enseignement/processus-naturels/up1/web/wiki/Q%20-%20Tectonique%20-%20La%20formation%20de%20la%20chaine%20de%20montagnes%20%20Alpes%20-%20Martin.htm

http://geologie-alpe-huez.1001photos.com/roches/ocean.php

http://www.reseau-canope.fr/svt-taches-complexes/chapitre.html?page=tt1st2c2ua

https://ft.univ-tlemcen.dz/assets/uploads/pdf/departement/gc/houti/Chapitre-4-NOTION-SUR-LA-TECTONIQUE.pdf

https://docplayer.fr/8422905-Les-plis-partie-1-geometrie-et-representation-stereographique.html

Questions

The careful reading of the cache description, as well as an observation of the field elements and a little deduction are normally sufficient to answer the questions of this EarthCache.

From the listing coordinates, look at the ridge in the foreground to the west, on the other side of the Glacier Valley, and answer the following questions:

1. Using the listing, assign each of the zones A, B, C, D and E (see picture "Zones") to the different rocks described.

2. Using the geological time scale, specify the geological period and time of rock formation in each of these areas (example: Middle Devonian).

3. According to the chronology described, which are the areas corresponding to rocks formed from oceanic sedimentary deposits?

4. Is the most recent past more likely to be in Zone A or Zone E? Why might this seem surprising?

5. According to the time scale (image "Time scale"), how many millions of years of rock formation history do you have before you with these 5 zones?

6. Take a closer look at area D (Large Scale, see picture "Zone D"). You will see a testimony of the tectonic constraints suffered by rocks during the formation of the Alps. Determine the type of fold (straight, depressed or lying) and its orientation (dextral or senestral)?

Optionnal: a picture of you or your GPS on site is not mandatory but highly appreciated ^^

You can log in without waiting for our confirmation, but

you must send us the answers at the same time either by email via our profile or via geocaching.com (Message Center). If there are any problems with your answers we will let you know.

Logs recorded without answers will be deleted .