Introduction to Millstone Gritstone

When any rock erodes the hardest strongest bits are what survives the longest. This is a very quick and easy EarthCache that explains a common sight throughout the Peak District moors and there is a good example of it here. Many of the paths in the Peak District look like they are coated with a white sand, but the grains are quite large and shiny. This is because quartz is the toughest component of gritstone and it's survival often creates a unique and special natural surface on paths and tracks up here.

Background to Gritstone

Firstly, we need to understand the basic formation of the rock you see here today. The northern Peak District is bounded on east and west sides by sandstone scarps. They are made of a rock often called "Millstone Grit". This is in fact a catchall for a variety of coarse sandstones, referred to here as "grits". The name "Millstone Grit" came about because certain varieties of Gritstone were commonly used to make millstones. Gritstone is actually a variation of sandstone and is made from sand, grit and rounded pebbles of quartz and some feldspar. The name ‘grit’ is used for many local sandstones and indicates the coarseness of the quartz grains in the rock, although the size of the particles in the sandstone is variable. Most of the sandstones of the Millstone Grit are coarse, with grains larger than 0.5mm and there are white quartz pebbles up to 10mm, especially in the Kinderscout Grit.

Gritstones were laid down in the delta of an immense river which flowed from a mountainous area. The land was below the sea, and every tide, every flood, dumped sand onto the sea floor. Generally the layers were thin and/or disturbed by currents. Occasionally some event would occur which laid down layers many metres thick in a very short time. All this happened around 300 million years ago, long before the dinosaurs. Eventually the grits were buried by muds, coal, and limestones. The layers of sand, under pressure and subject to chemical change, became rock. Eventually what is now England was pushed up out of the sea and erosion began creating all the gritstone formations you see up here today.

Survival of the Hardest

Gritstone is made of of three main components. As erosional forces attack the rock it slowly erodes away and there are many examples of gritstone eroding up here. But what exactly happens when it erodes and what is left of the three components when the erosion has taken effect?

Sand and Grit

Gritstone is a type of sandstone and therefore contains sand grains as you would expect to find in sandstone. It also contains sand grains known as grit, this is a general term to describe larger angular sand grains. As it erodes, the sand grains come away from the rock as individual grains. These blow away in the wind and add to the landscape, eventually entering the water channels and perhaps ultimately helping to form new sedimentary layers in oceons miles away. These grains are very small and once they have broken away from the rock many could be too small to see (perhaps the sort of annoying speck that blows in your eye!). Other larger grains will remain, but of course over time the largest grains themselves may break now and become smaller.

Feldspar

Feldspar is the name of a large group of rock-forming silicate minerals that make up over 50% of Earth’s crust. They are found in igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary rocks in all parts of the world. Feldspar minerals have very similar structures, chemical compositions, and physical properties.

In sedimentary deposits produced from the weathering of feldspar-bearing igneous and metamorphic rocks, feldspars are usually most abundant close to the source area. Feldspars generally decline in abundance with distance from the source because during transport, they can be attacked by weathering and altered to clay minerals. In addition, their two directions of perfect cleavage make them vulnerable to mechanical weathering, which decreases their particle size and exposes a greater surface area to chemical weathering.

Feldspar only begins to chemically weather when exposed to water or acid environments on the Earth's surface. When this happens, it is chemically weathered by hydrolysis. This is the reaction between a water molecule and an ion in the feldspar that releases a hydrogen molecule, which becomes attached to a separate product. The result in solution is Kaolinite, which is a layered silicate clay mineral.

Quartz Pebbles

Quartz is one of the most common minerals in the Earth’s crust. As a mineral name, quartz refers to a specific chemical compound (silicon dioxide, or silica, SiO2), having a specific crystalline form (hexagonal). It is found is all forms of rock: igneous, metamorphic and sedimentary. Quartz is physically and chemically resistant to weathering. When quartz-bearing rocks become weathered and eroded, the grains of resistant quartz are concentrated in the soil, in rivers, and on beaches. The white sands typically found in river beds and on beaches are usually composed mainly of quartz, with some white or pink feldspar as well.

This is why you often see little white pebbles in the paths and peat on the hills around here. A pebble is a clast of rock with a particle size of a particular size (see below). So when you are walking down a path up here covered with white pebbles, you might just be walking on a path naturally paved in quartz! Up here the gritstone is eroding all the time and the main bit that often remains is the quartz crystals that don't weather away. They blow about being very small and light but often stick to exposed peat or accumulate in dips, such as paths and tracks.

Grain Size Classification

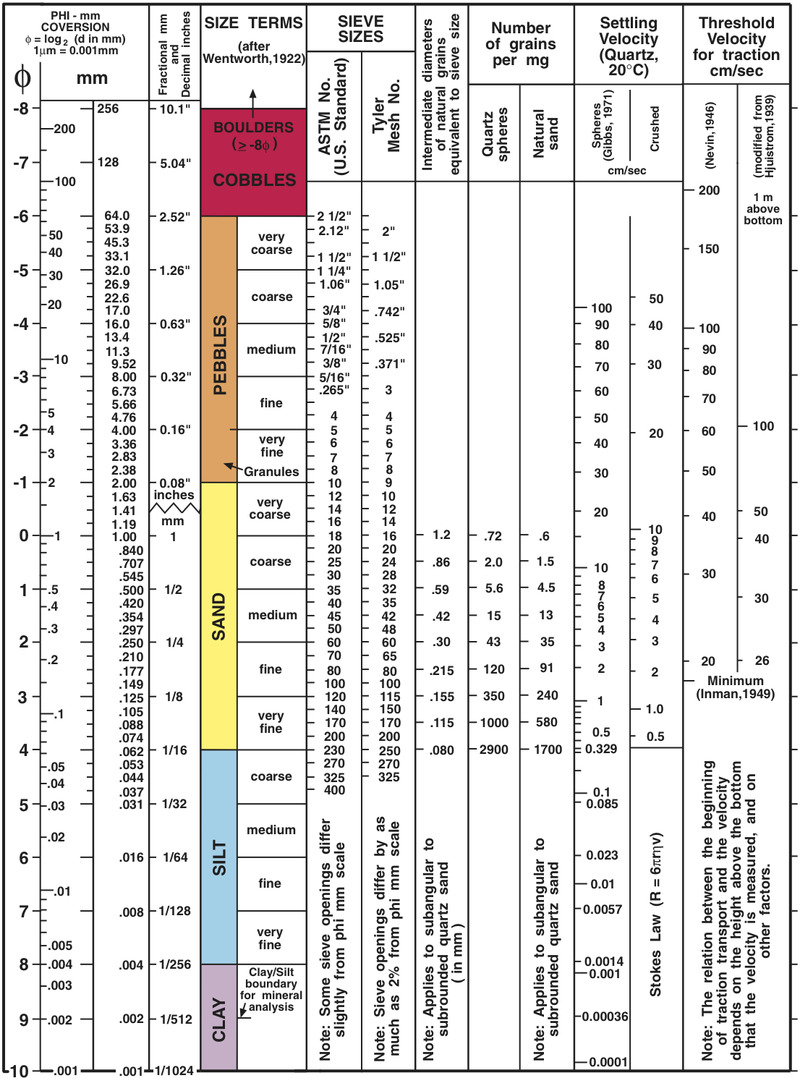

The Wentworth scale, shown below, is often used to classify the size of grains found.

Questions to Answer (Logging Requirements)

Please visit the listed coordinates and examine the surface of the track here. The questions all relate directly to the information provided in the listing so you should be able to answer everything from GZ with no extra reading required. Please ensure you send in the answers at the time or soon after you log your find, as logs may be deleted if no attempt at the answers are made.

1) Please look for quartz pebbles in the track. Feel free to move a little from GZ if you don't immediately spot any. Please describe the biggest and smallest sizes according to the scale provided (so we can understand the range of sizes), and also comment on the texture and condition of the pebbles.

2) Please look for any none quartz grains making up the path. Disregard anything larger than pebbles - what else can you see and what are their sizes according to the Wentworth scale?

3) Look for any other larger stones seen in the track. Are they the natural local stone type (gritstone) or something else? Do you think they got here naturally or have they been brought in from elsewhere by whoever built the track?

Please note. Non spoiler photos are always welcomed. At the time of publication if you are in an area where there is no signal and you write your answers into the message center it will not queue the message to be sent later as it does with logs - instead it will be deleted immediately by the app if it fails to send. Please be aware of this as I need to receive your answers. If you don't get a pop up saying 'message sent' then it hasn't!

Thank you for visiting the Paved with Quartz EarthCache