My kids often ask about what Native Americans lived around here before European settlers arrived. The easy answer they’re taught in school is that these were the Lenni Lenape people (also called the Delaware Indians), and that they no longer exist. But that’s both over-simplified and untrue — the Lenape were a large grouping of several connected bands, including the local Hackensacks (or Ackingsah-sacks), and although they split into different groups that now live from New York and Canada to Wisconsin and Oklahoma, a couple core groups still live on reservations here in New Jersey—most notably the “Ramapough Mountain Indians,” or more properly the Ramapough Lenape Nation, near Mahwah and Ringwood.

(Before we fault the teachers, I should say that most sources that mention the Lenape people write them off as extinct, often to serve the good-intentioned narrative that they were exterminated by disease, war and land theft perpetrated the colonial immigrants —while all of that is true, it also erases their impressive story of perseverance despite all of it.)

Back to where you’re standing: While it was within Hackensack “territory,” the area of West Orange wasn’t, as far as we know, a “settled” area — more sedentary in their lifestyle than some other tribes, the Hackensacks were based near the town that today bears their name, where they had permanent settlements and farms. But as many of us do today, after planting their crops in spring they also moved down to the Jersey Shore for the summer, following their main road that ran south along the west side of these mountains down to Chatham, where it crossed the Passaic River and headed East to today’s Perth Amboy. While there’s no way to know their road’s exact route (outside of main thoroughfares like nearby Northfield Ave. or Old Indian Road, which follow connecting paths to the east), this trail you’re on is meant to commemorate it as it follows its general direction.

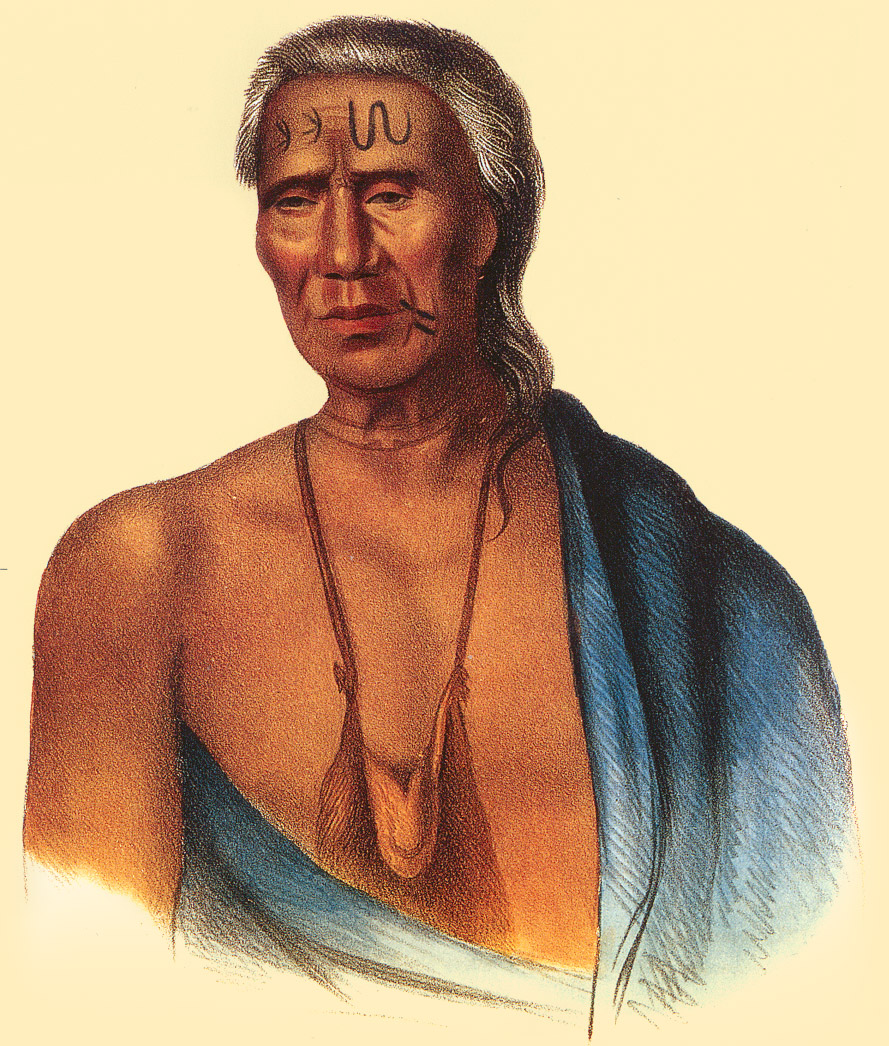

Colonists who came into contact with the Hackensacks were stunned with their generosity and friendliness, describing them as a tribe that seemed to put special value in giving what they had to guests and visitors. "None could excel them in liberality with the little they had,” Samuel Smith wrote, “for nothing was too good for a friend." They were also taken aback by their advanced skincare: "They preserved their skins by anointing them with the oil of fishes, the fat of eagles and the grease of raccoons, which they hold in the summer to be the best antidote to keep their skins from blistering by the scorching sun, and their best armour against the musketto's [sic: mosquitos] and stopper of the pores of their bodies against the winter's cold."

By the time they came into regular contact with the Dutch settlers of New Amsterdam, the Hackensacks were already reduced from as many as 20,000 people to around 1,000, due to more than a dozen separate pandemics of European diseases, and had been defeated in battle by the Iroquois. They were regarded in council by their fellow Algonquian tribes as being particularly wise and older than many of their neighboring tribes. In their language, the name Lenni Lenape meant “The Original People.”

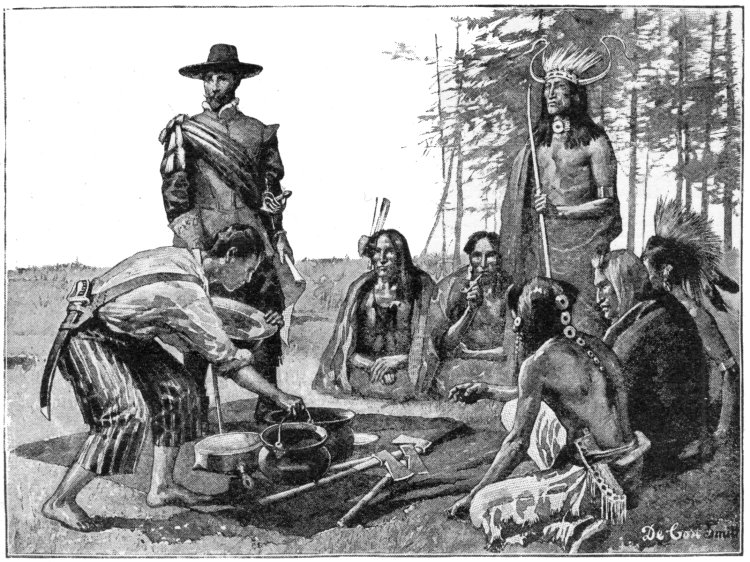

The Hackensacks (and broader Lenape) traded with the Dutch colonists of New Netherland at Communipaw, Pavonia and Hoboken, mostly peacefully, trading beaver pelts and wampum belts for tools, gunpowder and alcohol (which created problems for a people with no experience with drinking, to the point that their sachems attempted to outlaw it). But as settlers encroached more and more into their territory, the Lenape were forced to give up their land, first along the Hudson from Weehawken west to Secaucus.

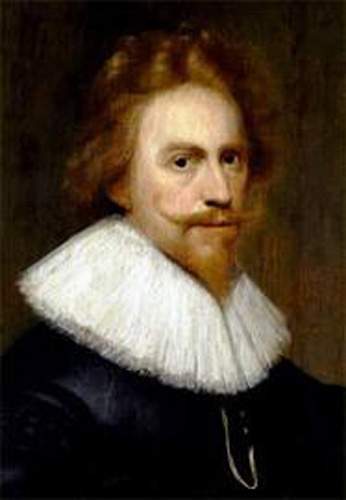

On February 23, 1643, Dutch commander Willem Kieft, against the pleas of the New Netherlands council, launched an unprovoked surprise attack against friendly Lenape who were seeking Dutch protection that would become the first genocide of Native Americans carried out by the colonists, forever known as the Pavonia Massacre. That night, more than 120 Lenape, mostly women and children, were murdered.

Dutch council president David Pieterszoon de Vries, who had opposed the attack, later described in horror what happened: “Infants were torn from their mother's breasts, and hacked to pieces in the presence of their parents, and pieces thrown into the fire and in the water, and other sucklings, being bound to small boards, were cut, stuck, and pierced, and miserably massacred in a manner to move a heart of stone. Some were thrown into the river, and when the fathers and mothers endeavored to save them, the soldiers would not let them come on land but made both parents and children drown...”

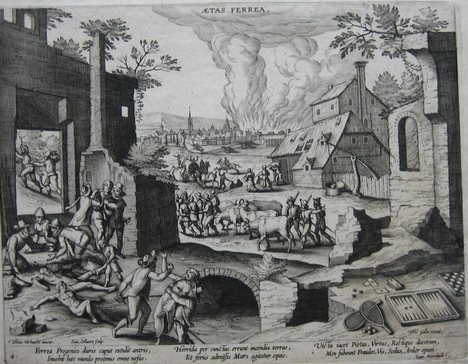

Although de Vries negotiated an uneasy truce between the Dutch and the Hackensack sachem Oratam, and Kieft was eventually recalled to Holland to stand trial (he died on the return voyage), the peace didn’t last — the Lenape unified their different bands and retaliated, eventually burning every European settlement on the west side of the Hudson and driving the Dutch back into Fort Amsterdam on Manhattan, which 1,500 Lenape warriors also attacked, killing settlers and burning homes in a two-year conflict known as Kieft’s War that would eventually claim more than 1,500 lives.

Although they had been proud of being known as a peaceful tribe, the Lenapes’ further interaction with the colony became marked by more warfare provoked by the Dutch (which Lenape history proudly points out repeatedly resulted in Lenape victories over the Dutch in battle). By the time the British conquered New Amsterdam from the Dutch in 1664, the Lenape had already begun moving west away from the colonists. In 1666, they sold the area that would become Newark and the Oranges to Robert Treat, and Dutch and English settlers began moving in and clearing land for their own farms.

The rest of Lenape history is a sadly common story of repeated treaties signed and then broken by the colonists, followed by successive moves to areas considered less desirable by white settlers: northwestern New Jersey, Burlington (home of the country’s first ever Indian reservation, called Brotherton), New York, Canada, Indiana, Wisconsin, Texas and Oklahoma. In the process the tribe fragmented, with different bands banding together with other groups. Today the Lenape are spread in many of these locations, with remaining groups still on some of their traditional land in New Jersey on the state’s two recognized Indian reservations.

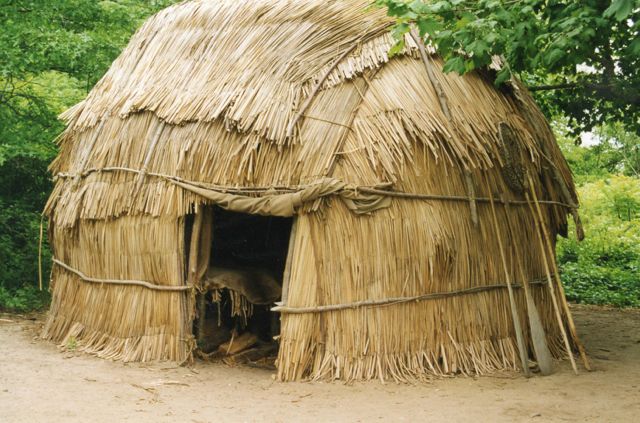

(For anyone who wants to learn more about the Lenape, there are recreations of their traditional homes and village areas at the Essex County environmental center in Roseland and at Waterloo Village.) The Lenape Trail, commemorating their history through beautiful nature, runs 34 miles in an arc from Millburn through West Orange and Montclair, then curving over through Newark.

As for the cache: You’re looking for a plastic ammo can with plenty of room for toys and trackables. Like the 20-minute hike to it, it’s not overly difficult, but may take you a little while to find.

Congrats to BigA800 for the FTF!