Million Dollar View (Rock Dunder) EarthCache

Million Dollar View (Rock Dunder)

-

Difficulty:

-

-

Terrain:

-

Size:  (other)

(other)

Please note Use of geocaching.com services is subject to the terms and conditions

in our disclaimer.

My

inspiration for this cache:

Every since I started caching in 2008, I've had many interesting

geocaching experiences and have been taken to spots that have

simply amazed me. However, on October 10th, 2008, my geocaching

life was changed forever, for that was the day I did Yorkshire's

"Dunder Thunder" (GCXF76). I couldn't believe the view up there and

the beautiful hike up to Rock Dunder was amazing, it was at the

time and remains now, my favourite cache of all time. It really

personifies what a perfect caching experience should be. It's not

just about the cache, but about getting to the cache and being

introduced to something you've probably never seen before. I have

since made the climb to Rock Dunder about 15 times with family and

friends, getting excited each time I go in anticipation of what

that experience will bring. So today when I went for hike #16, I

decided that this would be a perfect spot for an Earthcache, given

all the obvious geology around.

The geology and things you may want to

know about Rock Dunder:

Rock Dunder is shown on some geological maps as a

pluton. On others it is part of a much larger igneous feature

termed Lyndhurst granite. But beyond definition, Rock Dunder is a

remarkable formation of beautiful pink granite. It took form deep

in the roots of the Grenville Mountains that a billion years ago

towered over this part of Laurentia. We can call this core of our

continent the Canadian Shield. These massive snow-capped ranges and

deep unforested valleys once extended north-east to present-day

Labrador and south-west to Kansas. In fiery ovens deep beneath

those mountains, plutons such as Westport Mountain and Rock Dunder

were formed, their mineral recipes were baked. Earthquakes in

Indonesia remind us that mountains are still being heaved up when

and where the plates of our planet’s thin crust jostle and

collide. Volcanoes erupt on land and beneath sea. Plutons are

forming within the crust as they did a billion years ago.

Conversely wind, water and ice eternally wear mountains down even

to their very cores. The Ice Ages of the Pleistocene Epoch occurred

within the last mere million years of our planet’s history.

That choreography of ice did much to sculpt Rock Dunder’s

ancient and hard pink granite into its present shape on the Rideau

Cataraqui landscape. Indeed, several great advances of continental

and alpine glaciers occurred during the Pleistocene across the

higher latitudes and altitudes of North America and all other

continents. These advances were interspersed with interglacial

phases; millennia of climate much like the present. Our most recent

Ice Age (the Wisconsin) seems to have begun about 100 000 years

ago. Shorter summers failed to melt all the winter snow that fell

on the highlands of Quebec and Labrador. Delicate snow flakes

packed into layers of bluish ice along with bubbles of air, grains

of pollen from distant flora, particles of ash from volcanoes and

forest fires half-the-world away. When annual layers of ice

accumulate to a depth of about 50 metres, a glacier is born. It

starts to flow under its own weight like icing on a cake; oozing

and sliding outward and/or southward a few metres to several

kilometres per year. From Northern Quebec and Labrador, the

Laurentide Ice Sheet crept south into the St. Lawrence Valley,

across eastern Ontario and as far south as New York City.

To the west, the Laurentide teamed up with the continental ice

sheet that was spawned on the highlands of Keewatin. Together, they

bulldozed as far south as Wisconsin. Like Caesar’s army, the

Wisconsin Ice Age came. It conquered. It melted away. It melted

from its gravels and boulders piled on New York’s Long Island

about 12 000 years ago. About the same time it melted from the

bouldery moraines it had bulldozed onto Wisconsin. It finished

face-lifting Rideau country roughly 10 000 years ago. It melted out

of Hudson Bay about 5 to 3 millennia ago. You and I are helping its

disappearance from the Arctic now.

The Wisconsin Ice Sheet was not only composed of layers of ice. It

carried in its sole fragments of rocks picked up as it slid

southward; fragments as tiny as clay platelets; boulders as big as

your house. Some fragments were very hard, like pebbles and

boulders of quartzite that could survive hundreds of kilometres of

transport and grinding. Some diamonds from Inuit lands of the

present were exported to the northern U.S.A. Soft soapstone did not

survive the trip.

Here in Rideau country, glacial flow was from north-east to

south-west. Coincidentally this was the same orientation as the

ranges, valleys and roots of the Grenville Mountains of a billion

years ago. The Wisconsin Ice Sheet was 2 to 5 kilometres thick. It

oozed across the countryside, flowing around and even up and over

mere rocky obstacles like the hard granite of Rock Dunder.

Conversely, the soft skarn beneath nearby Morton Bay was gouged and

deepened. Murphy Bay on the Big Rideau and most local bays and

lakes were gouged and deepened, north-east to south-west. Canoe

Lake and Loughborough Lake are fine examples of long, narrow lakes

sculpted by the ice sheet. The fabled Finger Lakes of New York

State became the ancestral waters and shores of the Iroquois. If

such deep and narrow basins were adjacent to a sea or an ocean,

they would be filled with salt water rather than fresh water. They

would be called fjords like you would see along the coasts of

Norway, Labrador and the west coast of Newfoundland.

The Wisconsin Ice sheet oozed over the hard granite of Rock Dunder

like a massive sheet of sandpaper. It polished the north-east

(stoss) end and its flanks. In some places, hard rocks in the sole

of the ice sheet chipped half-moon shapes in the granite, crescents

called chatter marks, notes in the “sole music” of the

Ice Age. At Dunder’s south-west end something quite different

happened. Even the hardest of granite has cracks called joints,

some very visible, some microscopic. As the ice sheet made its way

over the lee end of Dunder, it tugged and pulled on these lines of

weakness much the same as you might fan a deck of cards with your

thumb. Blocks of Dunder’s hard pink granite were pulled away

by the oozing ice and were then used to gouge and polish more

southerly lands. This left the south-west end as a very sheer cliff

many metres high.

Cliffed at the lee end, gently polished at the stoss end; these are

features of a glacial landform called a roche moutonnée; a

“stone sheep” in French. Rock Dunder is one heck of a

big sheep! And a pink sheep at that! Maybe the term came about

because flocks and shepherds found refuge from cold winds and

blizzards sweeping down Alpine valleys. Maybe the cliffed lees of

roche moutonnées were giant motherly ewes of stone. Indeed, at the

base of the shear south-west end of Rock Dunder we discovered, not

sheep but an amazing ecosystem. Here trees and smaller plants

typically found far to the south are protected from cold north

winds and nurtured with extra warmth by sun’s energy

re-radiated from its granite backdrop. In this tiny Garden of Eden

we found American Linden trees at the very northern limit of their

habitat. On the opposite or north-east end of Dunder, more exposed

to wintry north winds and more oblique to the sun’s rays, we

found trees and mosses typical of more northern latitudes. This

tells of the incredible biodiversity to be found on every hill,

every island in Rideau country.

The Earthcache, the hike and what you have to tell CZ to get a

smiley:

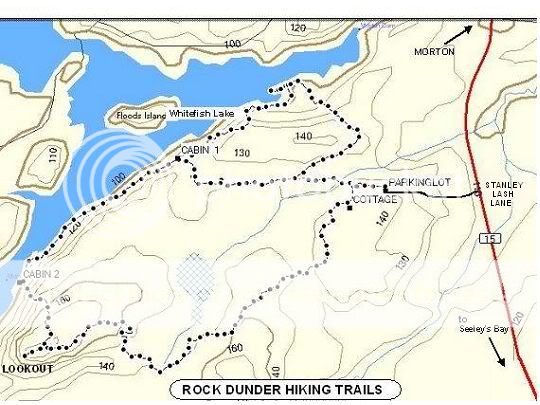

So you've made your way to Morton, found the

entrance to the parking area and are ready to go for a hike. There

are a few things you should know before committing yourself to the

task. The distance from the trailhead sign to Rock Dunder is

about 1.5 kilometers as the crow flies, however as the trail goes,

it's going to be a little further. There are maps and a trailguide

at the trailhead sign that will assist you, but the north trail is

very well worn and marked. There are two trails to take you to the

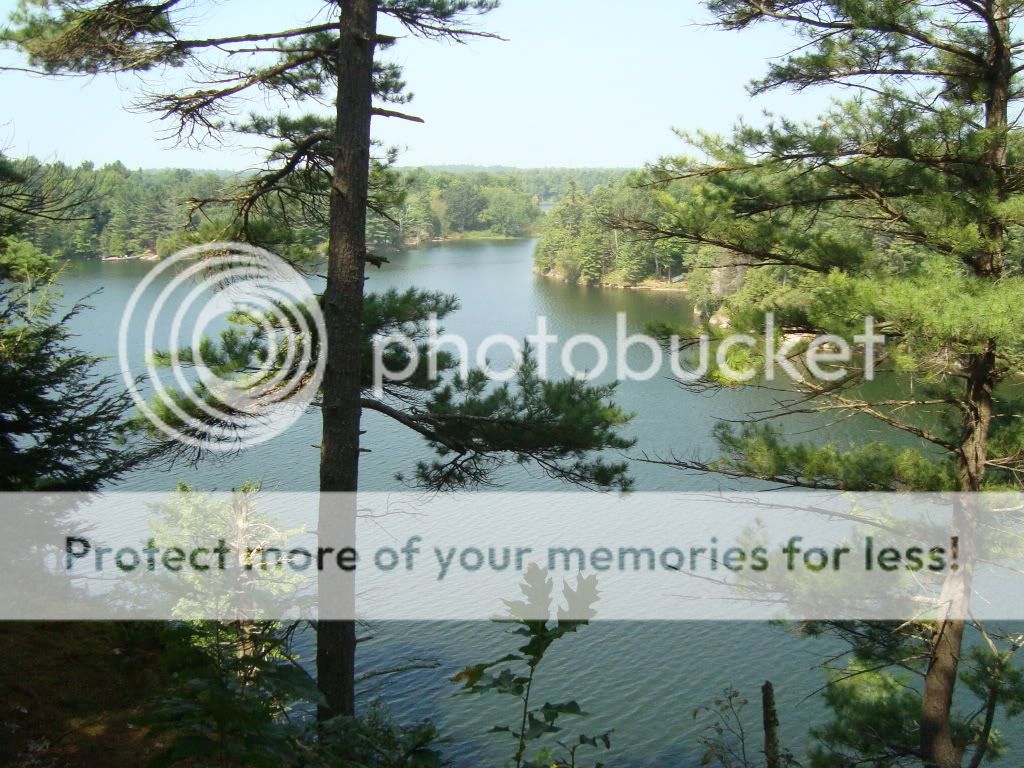

top, but I'd suggest staying to the right and taking the north

trail. It's very scenic, offering great views of the water on the

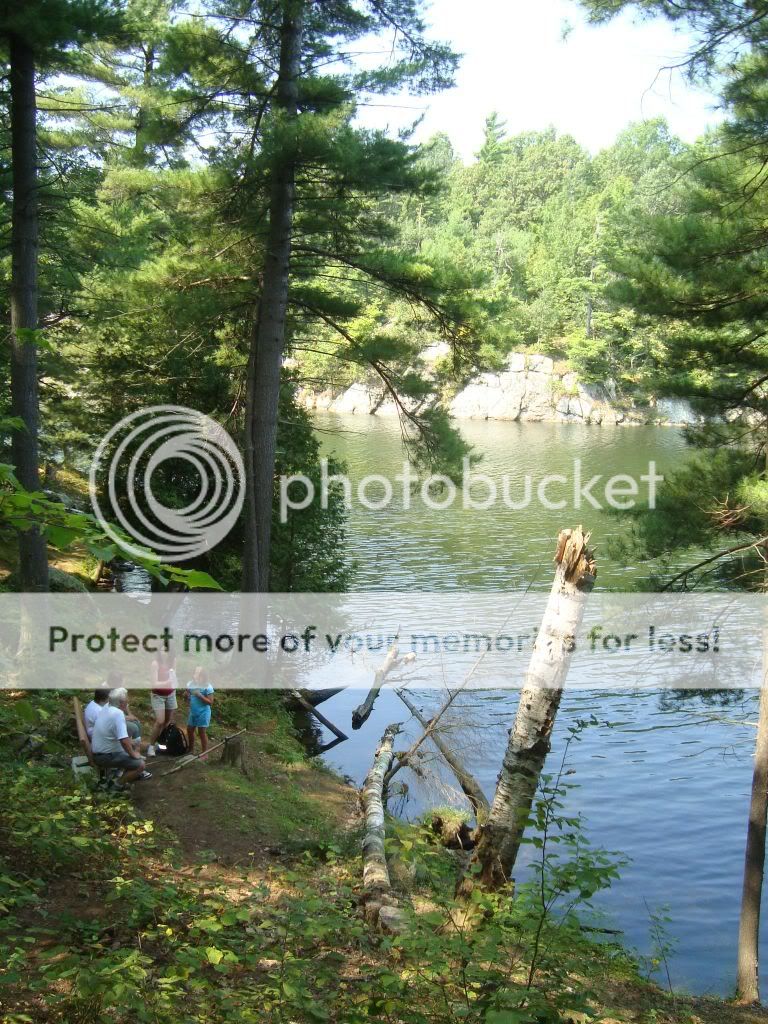

way up. There are also multiple benches for resting and two cabins

on the way up to take a break as well.

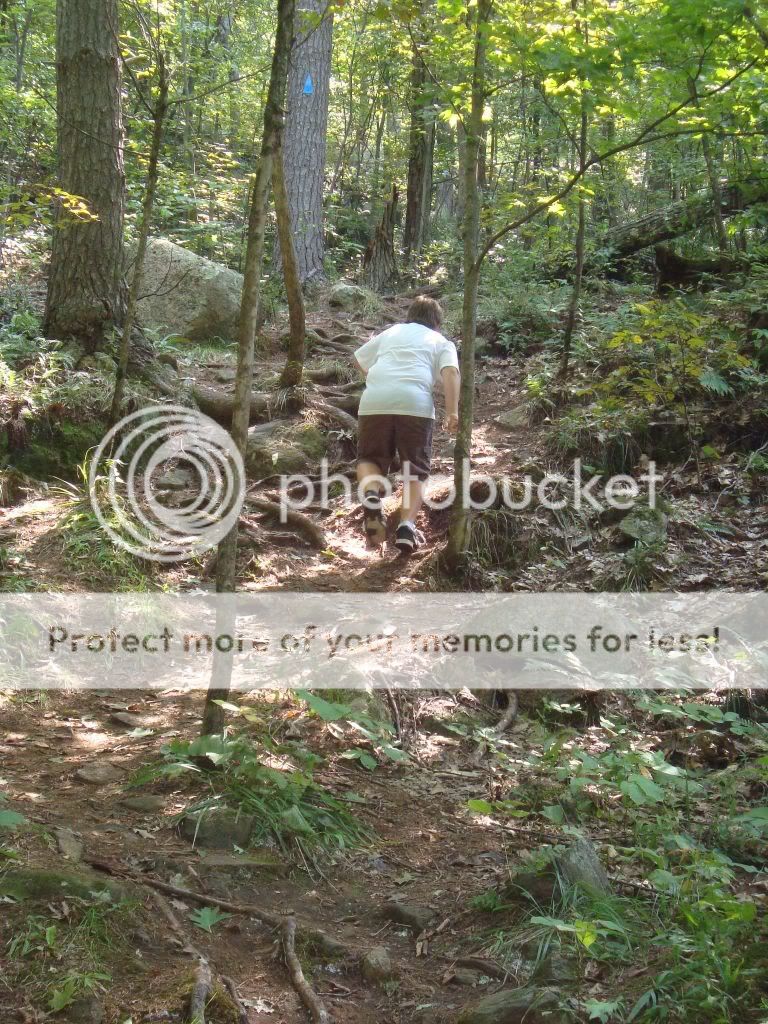

The trail starts out fairly flat and becomes a little more rolling

the closer you get to the water. I would suggest parents with young

children monitor their young ones along this route as there are

spots that have steep drop offs if you get off the trail too far,

however, I have taken my children here since they were 7 and 9 and

we've never had any problems. You will find the trail becomes

somewhat more rolling when you get past the first cabin, but again,

my 65 year old father has done this trail with me several times and

has done fine. The trail starts to go "up" significantly after the

second cabin, but again, nothing that requires special equipment

and for the most part you will remain on two feet and not require

the use of your hands to pull you up a rock. After this brief, but

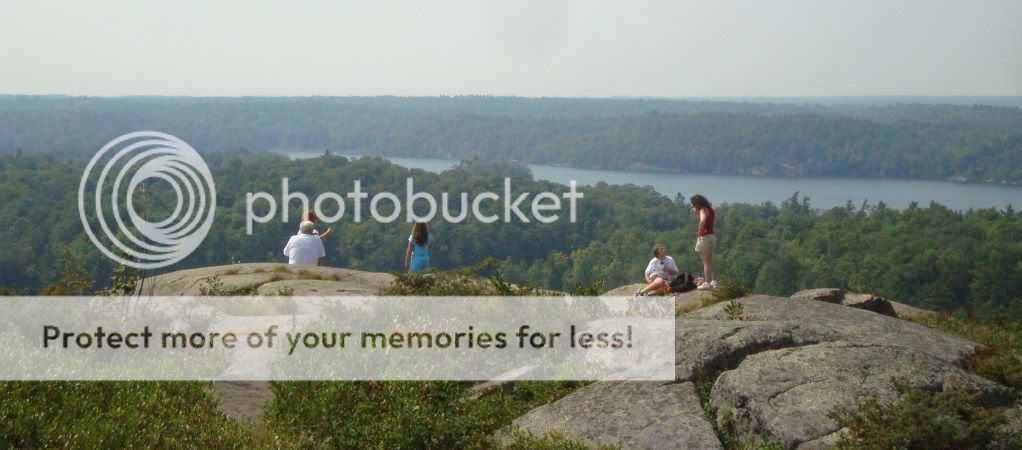

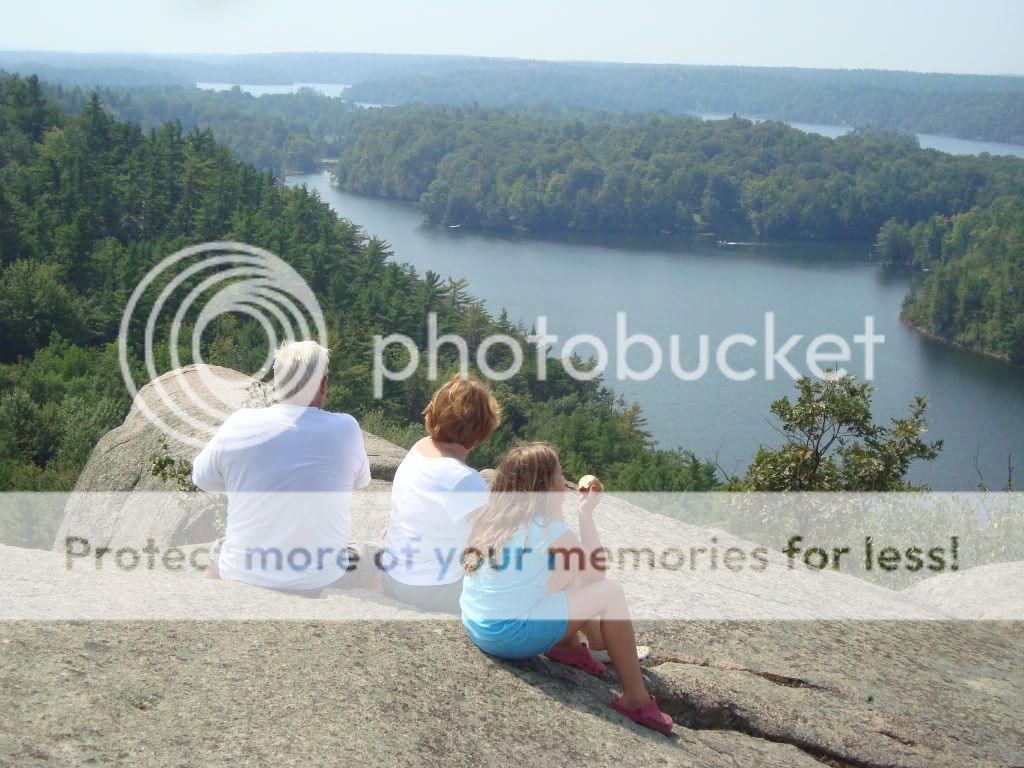

energizing section is completed, you need only walk through some

scrub brush and you'll be at the one of the most amazing views in

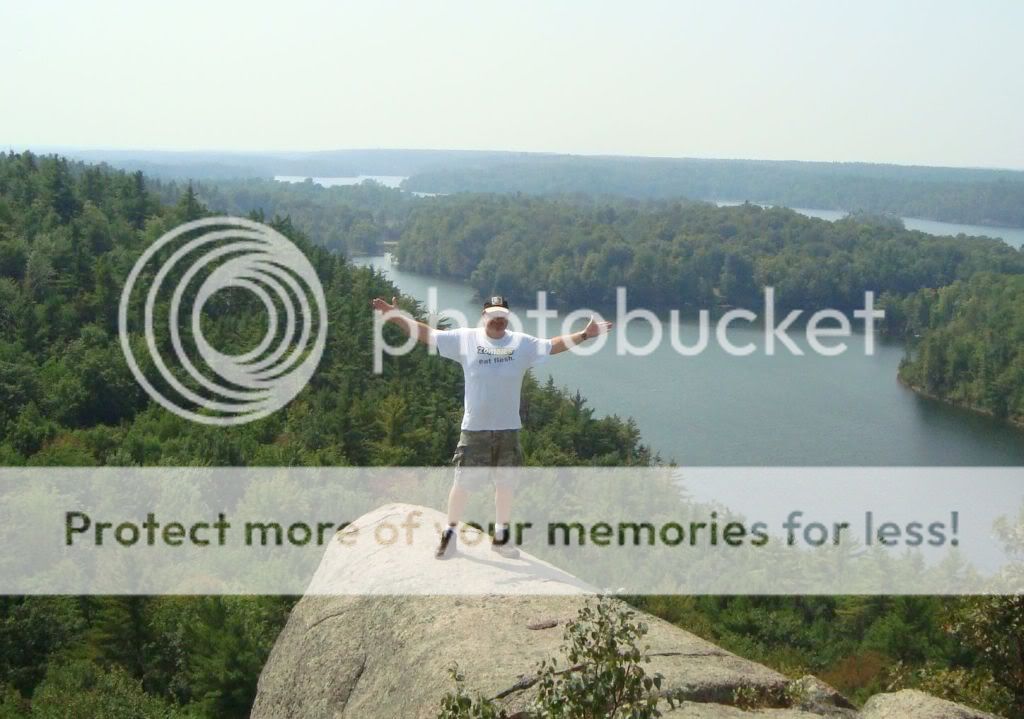

this part of Ontario. You'll be close to 300 feet over Morton Bay

with a view that will take your breath away. You'll see Turkey

Vultures flying overhead and boats traversing the water (if you do

it it summer) way down below. Again, my suggestion is for people

that have little ones is to keep an eye on them around here. There

are plenty of spots to sit and enjoy the view far from the edge and

safe for curious little ones.

Now just take a deep breath and enjoy the total awesomeness of this

spot, it's truly awe inspiring and I promise, you'll love this spot

forever as I do.

Now that you've made it up here, what will I have you do? Well if

you look around, you'll see a variety of different glacial

formations here, but I'm only going to ask about a few, here's what

I want. Please send send me these answers to my geocaching.com

address and please don't post them or any spoiler pics in your

cache log or your log will be deleted. Now, on to your tasks:

#1: At N 44 31.669 W 076

13.118 or Glacial Feature

#1, please tell me what you're seeing in the rock. It's

bigger than a wheel, but smaller than a car.

#2: At N 44 31.612 W 076

13.139 or Glacial Feature

#2, please tell me what those marks at your feet are

called.

#3: At N 44 31.921 W 076

12.190 or The Trailhead

Sign, take a measurement of

your elevation above sea level, this can be in meters or feet, then

when you get to N 31.577 W 076

13.191 or The Million Dollar View, take another measurement of your elevation and tell me

the difference in meters or feet.

#4: Take a picture of yourself or your gpsr (if you're shy) at the

top of Rock Dunder and either send it to me via e-mail or include

it in your log entry.

I hope that this Earthcache will have taught you something about

our local geology and given you some positive memories that you'll

have forever. As with all CZ caches, the most important thing is to

have fun and be safe, please do both here.

Additional Hints

(No hints available.)