Calgary Building Stone Tour: Tyndall Limestone EarthCache

Calgary Building Stone Tour: Tyndall Limestone

-

Difficulty:

-

-

Terrain:

-

Size:  (not chosen)

(not chosen)

Please note Use of geocaching.com services is subject to the terms and conditions

in our disclaimer.

This EarthCache is the first in the Calgary Building Stone Tour

aimed at highlighting the remarkable decorative building stones

used to ornament many of Calgary’s buildings.

Note: The cache is not limited to the posted

coordinates. This cache may be logged at any building in Calgary

decorated with this building stone.

Limestone is commonly used as building stone in North America, but

Tyndall Limestone is unique. The colour, beauty, strength and

durability of Tyndall Limestone has allowed for it to be used in a

variety of ways and architectural styles. Tyndall Limestone is used

extensively as an ornamental building stone across Canada.

Look at the walls next time you see a news report from the halls

of the Parliament in Ottawa. The backdrop of elaborately carved

walls, columns, and ceilings are made of Tyndall Limestone. Other

notable buildings adorned with Tyndall Limestone include the

Canadian Museum of Civilization in Gatineau, the Manitoba

Provincial Legislature in Winnipeg, the Rimrock Hotel in Banff, the

Empress Hotel in Victoria, the Provincial Museum of Alberta, and

the University of Alberta’s Tory Building. Several buildings of

downtown Calgary are also decorated with the ornamental building

stone. The first building to be adorned with Tyndall Limestone was

Fort Garry in Manitoba in 1832.

Occurrence and History of the Tyndall

Limestone

Tyndall Limestone is an informal term applied to building stone

from the Selkirk Member of the (Ordivician) Red River Formation.

The best exposures of the Tyndall Limestone are found in the

Garson-Tyndall area, approximately 30 km northeast of Winnipeg,

Manitoba. The small village of Garson Manitoba bills itself as The

Limestone Capital of North America. This is no empty boast, the

limestone quarried here is probably the most frequently used

building stone in Canada. The name of the stone comes from Tyndall,

the closest railway point to the quarries; the railway station was

itself named after the noted British physicist Professor John

Tyndall.

Description of the Tyndall Limestone

Tyndall Limestone is a fine grained light coloured, fossil-bearing

limestone (wackestone) with comparatively darker brown coloured

fine to medium grained medium tubular-shaped (vermiform) branching

network of dolomitic limestone, which give the rock a ‘mottled’

appearance.

Two major types of fossils occur in Tyndall Stone. The first are

body fossils. These are the calcite shells of a variety of marine

animals and plants that lie dispersed throughout the rock -- like

raisins suspended in a pudding. The second are trace fossils that

occur as a pervasive network of burrows.

Body Fossils of the Tyndall Limestone

Body fossils are the hard, shelly remains of organisms preserved

within a rock. Tyndall Limestone is notable for its rich variety of

large, excellently preserved, easily-identifiable body fossils. A

close look at Tyndall Limestone will reveal many interesting

fossils embedded within it. The following is a non-inclusive list

of the most abundant fossils of the Tyndall Limestone that you may

find:

Cephalopods are like modern squids or nautili.

Cephalopods with straight shells are called Orthocone, whereas

those with a curved shell are known as Winnipegoceras.

Gastropods (Maclurites) are more commonly

known as snails and slugs. On a cut surface, the fossil may have a

coiled appearamce.

Chain Coral (Favosites) are colonial coral

that have an irregular grid pattern that sometimes resembles a

distorted chain-link fence.

Horn Coral (Grewingka) is a solitary

coral. In the rock the fossil has a pattern of line radiating out

to an oval or a horn-like pattern.

Sunflower Coral (Receptaculites), are the

largest and most enigmatic of the Tyndall fossils. Don’t let the

name fool you, they are not a corals, but actually calcareous

algae. The fossil occurs as a circular colony, characterized by a

uniform grid pattern and a distinguishable deep hollow in the

centre.

Brachiopods and trilobites may

also be present but are more difficult to identify. When examining

the rock for fossils, keep in mind that the shape of the fossil

displayed may vary considerably depending of the random

cross-section on the exposed surface of the building stone.

Trace Fossils

The shelly fossils of Tyndall Stone are certainly intriguing, but

it is the trace fossils that make this limestone an attractive

building stone. Unlike body fossils, trace fossils are fossilized

tracks, trails, or burrows left during the day-to-day life

activities of an organism. You may have unknowingly created trace

fossils with your own footprints, if they were subsequently filled

with sediment, buried and preserved in the geological record.

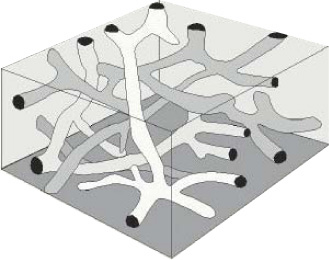

In Tyndall Limestone, the trace fossils are evident as a ‘mottled’

texture. The mottled areas have a tubular, vermiform shape that

branch and bifurcate, extending as deep as a metre below the seabed

surface. This image is a schematic block diagram of what the

network of burrows might look like in three dimensions.

These trace fossils are well-known to ichnologists (those who study

trace fossils) as Thalassinoides. Since the Cretaceous,

Thalassinoides tunnels have been excavated as dwelling and

feeding burrows by mole shrimp. However, it is unlikely that mole

shrimp or any other decapod crustacean made these deep burrows in

the Ordovician because these arthropods have a well-documented

fossil record that starts 250 million years later in Jurassic

rocks. So what animal made these burrows? Unfortunately, no body

fossils have been identified in or near the burrows to give even a

suggestion. One is tempted to say "worms", but when paleontologists

attribute a trace in sediment to the activity of "worms" it is

generally an expression of ignorance rather than an actual

identification. We simply don't know what animal is responsible for

the deep burrows and the mottles in Tyndall Stone.

The difference in colour between the burrows and the surrounding

rock is due to differences in grain size and chemistry. As the

animals burrowed through the soft, limey mud, they lined their

burrows with slime to add strength to their tunnels. Furthermore,

the sediment inside their burrows is loosened and reworked,

compared to the more tightly packed surrounding mud that hardened

before the less dense sediments in the burrows. Later,

magnesium-rich waters percolated through the rock and deposited

dolomite in the burrows, but couldn't penetrate the tightly

cemented limestone rock. The darker colour of the burrows may be a

result of oxidation of trace amounts of iron in the dolomite, or of

pyrite that was deposited along with the dolomite.

Depositional Environment

Four hundred and fifty million years ago (late Ordovician Period),

the environment of present-day southern Manitoba was a warm,

shallow, inland sea, just south of the equator. Many different

types of animals lived in this ocean. Some, such as corals,

sponges, molluscs, and algae, are still around today. Others, such

as trilobites and stromatoporoids, are extinct. All of these

creatures lived just below, on or above the soft, muddy sea floor.

After they died, their remains became part of it. The calcium

carbonate in their skeletons made the mud limey, so that when it

hardened into rock it became limestone. Fossils of these animals

and plants are visible today in Tyndall Stone. Other animals

burrowed in the mud of the sea floor for food or protection. And it

is the preserved burrows of these creatures that make the beautiful

mottling which gives Tyndall Stone its unique appearance.

More information can be found at the following site:

www.epl.ca/ResourcesPDF/Fossilsofcityhall.pdf

To log this cache:

In order to log this cache, you must:

- Estimate the average thickness of the burrows and email me the

answer

- Estimate the percentage of the rock that is composed of burrows

and email me the answer

- Take a picture of at least one body fossil with your GPS for

scale and identify it. Please post your answer as the picture

caption. I will be lenient with answers, but I will not accept 'I

don’t know'. Take a look at previous pictures to help you identify

your fossil. If you are unsure, post your picture anyway and take a

guess. If you are incorrect, I will help you identify it. All I ask

is that you modify the caption to the right answer because it will

help subsequent finders identify the fossils they have found.

- State the building and post your (best possible) co-ordinates of

where you made your observations in your log

Logs without an accompanying email or the required photo will be

deleted. Do not post a log for this EarthCache until you (a) have

emailed the answers and (b) are prepared to post the photo.

Happy EarthCaching!

References:

Canadian Society of Petroleum Geologists, 1997. Lexicon of Canadian

Stratigraphy, vol. 4: Western Canada. ed. D.J. Glass.

Geological Survey of Canada, 2006. Past Lives: Chronicles of

Canadian Paleontology - Tyndall Limestone.

http://gsc.nrcan.gc.ca/paleochron/17_e.php

Dixon Edwards, W. A., 2004. EUB/AGS Rock Walk IV - A Rock Walk

Through Downtown Edmonton. C. I. M. AGM tour and guidebook, May 12,

2004; in AGS Rock Chips, Fall/Winter 2003 edition.

http://www.ags.gov.ab.ca/publications/pdf_downloads/rockwalkhandout.pdf

McCracken, A.D., Macey, E., Monro Gray, J.M., and Nowlan, G.S.,

2007. Tyndall Limstone in GAC’s Popular Geoscience.

http://www.gac.ca/PopularGeoscience/factsheets/TyndallStone_e.pdf

Mussieux, R., and Nelson, M., 1998. Urban Geology: Building Stone

of the Provincial Museum and Government House. In: A Traveller’s

Guide to Geological Wonders of Alberta.

Additional Hints

(No hints available.)