A Earthcache é sobre Modelados Ígneos que são classsificações de geoformas que ocorrem nas rochas intrusivas e extrusivas. A classificação toma como variáveis o processo da sua instalação, bem como o processo de meteorização ou intemperismo a que ficam sujeitas. Esta Earthcache é sobre modelados ígneos que ocorrem em rochas ígneas intrusivas (nesta área, tendencialmente, Sienitos) e que apresenta algumas especificidades capazes de remeter à classificação de um TOR.

Retorna via mail do meu perfil com as respostas às duas questões obrigatórias. Por favor, coloca uma foto no teu found log que evidencie a tua observação in loco, para cumprires plenamente os requisitos para um log bem acolhido.

P1: Como descreverias o local do teu ponto de observação?

a) Não há blocos boleados, mas sim clara evidência de paralelipípedos com os blocos a apresentarem as arestas vivas e claras.

b) Já há alguns blocos arredondados, mas também blocos em forma de paralelos: uns na vertical, outros tombados na horizontal e outros inclinados (sub-horizontais e sub verticiais).

P2: É verossímel, afirmar a existência de uma gruta Talus no local?

P3: (opcional) Monumento antrópico ou monumento natural? partilha os argumentos que justificam a tua a opção que, se preferires, podes publicitar no teu log.

_________________________________________________________________

Para comprovar que se trata de um monumento megalítico haveria necessidade de uma pesquisa de campo que resultasse na descoberta de vestígios de facto. A pesquisa de campo foi conduzida, sem, no entanto, devolver qualquer artefacto comprovativo do seu uso funerário. Apesar de não cumprida essa mandatória exigência epistemológica, persiste a sua classificação como monumento cultural (Dec Lei nr. 136 de 16/06/1910).

Na serra, contudo, existem inúmeras "concavidades, grutas, abrigos" (GC3VNCX; GC80JY9; GC1H9V2), que se podem assemelhar a uma anta ou a um dolmen, mas são fenómenos naturais de desmonte, rolamento ou tombamento de segmentos de rocha provocados por meteorização ou o “processo de decomposição ou desintegração de rochas e solos (e seus minerais constituintes) por ação dos efeitos químicos, físicos e biológicos” (in Wikipedia). Na verdade, este fenómeno de tombamento, rolamento e empilhamento de blocos de rocha uns sobre os outros e que chega a formar verdadeiras grutas pelos espaços criados entre eles nesse processo, tem um nome - Talus (listing img 1) e trata-se de um arranjo morfológico típico de plutões ígneos como é a serra de Sintra.

A rocha agora exposta provém do manto superior. Tratava-se de uma rocha super aquecida que, ao ascender, arrefeceu e quebrou-se formando inúmeras fissuras em rede, tipo uma quadrícula. Uma metáfora para ilustrar este fenómeno é como colocar água quente num copo frio: o brusco contraste de temperatura resulta na quebra do copo em inúmeras fissuras. É o caso aqui! Essas fissuras são fragilidades que expõem a integridade da rocha aos agentes erosivos como a erosão pluvial, fluvial e eólica.

Quando as fendas se apresentam em malha, tipo rede (como é possível observar em muitos afloramentos no maciço eruptivo de Sintra!), a erosão tende primeiro a afetar os vértices dessa malha. Como consequência, esses afloramentos surgem como Boulders (blocos de rocha) de arestas arredondadas, com uma forma esferoide ou ovaloide, empilhados desordenadamente uns sobre os outros formando o que se chama de "caos de blocos" (listing img 2).

Neste local específico, contudo, a morfologia dos boulders não aparenta tanto ser um típico caos de blocos com os seus boulders tipicamente esferoides: aqui o talhamento da rocha ocorre nas mesmas fissuras em rede, mas numa geometria que mais faz lembrar paralelepípedos. isto acontece porque a sua erosão foi sobretudo provocada pela percolação da água na sua malha de fissuras. Esta meteorização tanto química como mecânica (provocada pela alternância de água no estado líquido e estado sólido o que lhe aumenta o volume em 9%), ocorreu enquanto a rocha ainda não se encontrava exumada (a descoberto), pelo que os agentes de abrasão como a energia eólica e fluvial, assim como a bio- erosão (eles próprios fatores de erosão à superfície), tiveram menor tempo para se manifestar, boleando as arestas, onde normalmente ocorre primeiro esta erosão. Assim, ao serem expostos pelos agentes erosivos em profundidade e antes de estarem a descoberto, o seu desgaste acompanha a rede de fragilidades verticais e horizontais, isto é, atuam na malha de fissuras existentes. Com o tempo e o alargamento dessas fissuras, os blocos acabam por se isolar e separar: por vezes mantendo-se precariamente na posição horizontal, outras vezes ocorrendo também muito precariamente empilhados na vertical uns sobre os outros, outras ainda tombados uns sobre os outros por falta de sustentação, mas mantendo sempre alguma simetria, mais parecendo que alguém lançou desordenadamente, as peças de um dominó sobre a superfície.

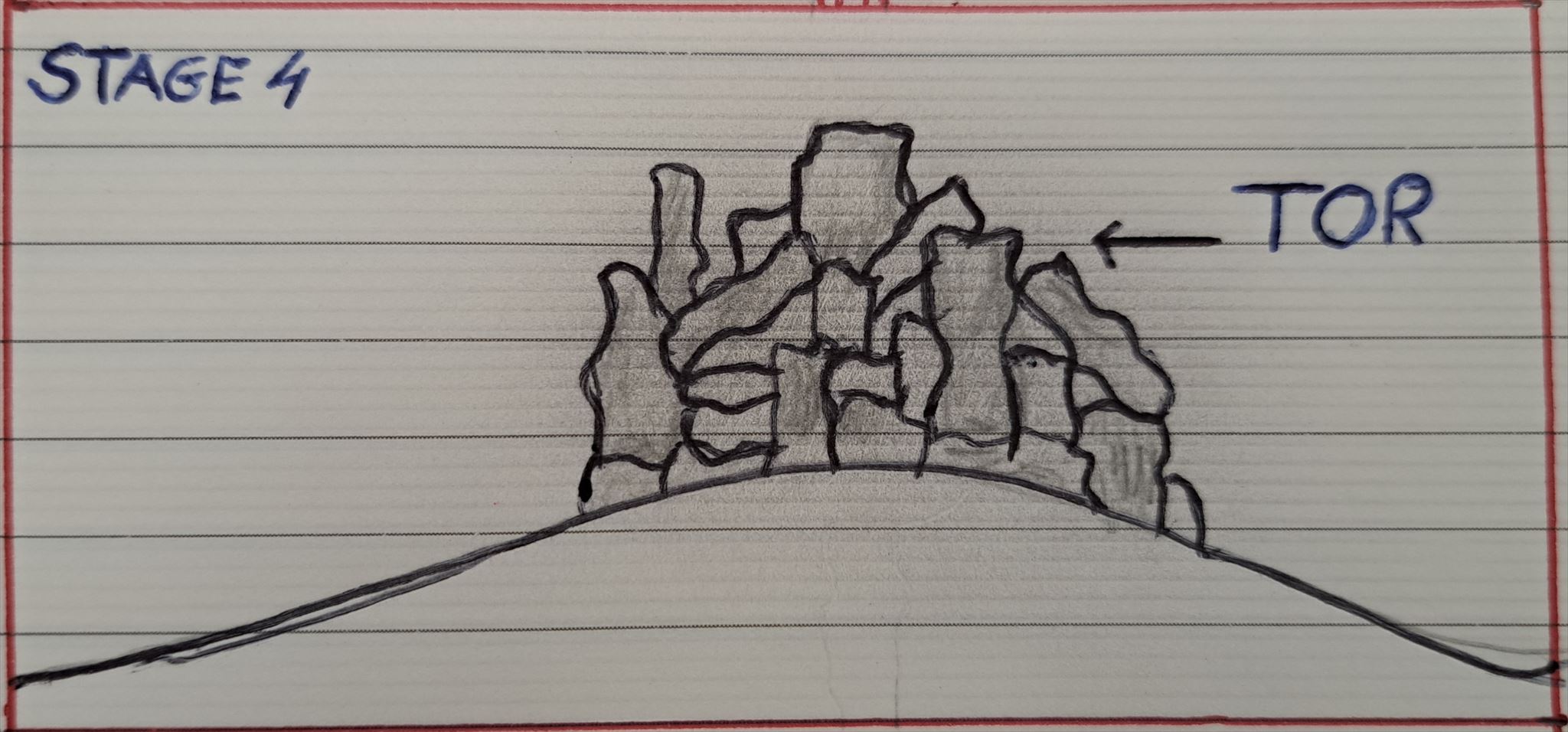

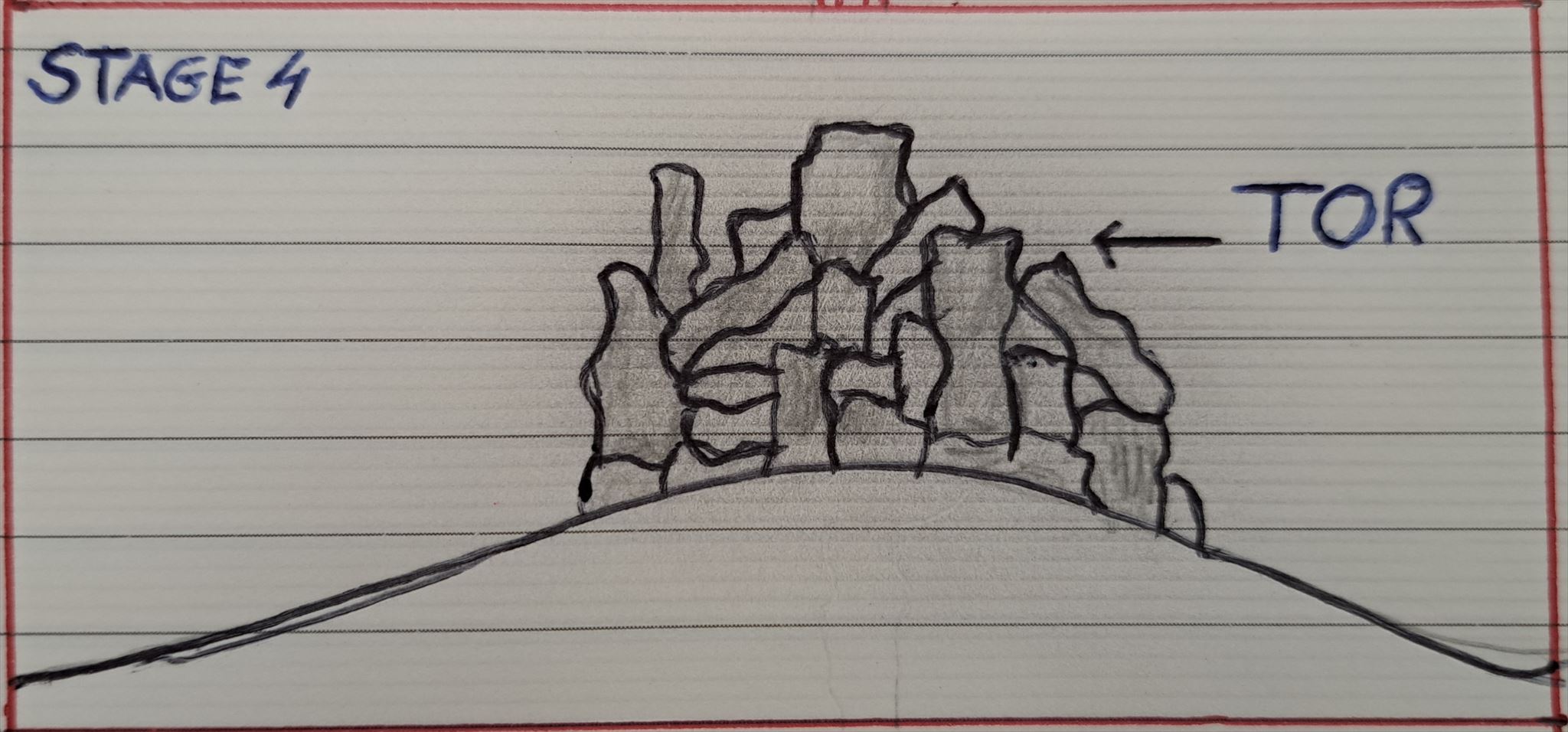

Dependendo da sua morfologia, assim se classificam os modelados graníticos. Este caso concreto da morfologia aqui presente, em Geologia, pode assumir a classificação de um TOR (listing img 3) porque, diferentemente de um caos de blocos esferoides, mais se assemelha a simétricas peças de dominó indiferentemente atiradas ao chão e que se organizam de forma caótica em empilhamentos, tombamentos e deslizamentos.

Se do ponto de vista monumental, esta aparente simetria é suficiente para a sua classificação antrópica, pode ser pouco consensual. Do ponto de vista geológico, contudo, é um local curioso pela demonstração comum, mas um pouco inaudita, das formas de erosão que afetam os granitoides, por vezes em modulados curiosos.

Como se formam?

A sua formação decorre dos processos de meteorização (desgaste, erosão) que mais facilmente afetam as fissuras da rocha em questão. Essas fissuras, ocorrem normalmente numa geometria de malha ou rede apresentando-se na vertical e na horizontal (listing img 4) e, tecnicamente, chamam-se DIACLASES:

- as diaclases verticais e sub-verticais ocorrem por TERMOCLASTIA, ou seja, pela recorrente variação de temperatura que promove a dilatação/contração térmica do corpo ígneo e este fissura-se (a tal metáfora do que acontece quando se coloca água gelada num copo aquecido e este se quebra em inúmeras fissuras verticais e sub-verticias).

- as diaclases horizontais ou sub-horizontais ocorrem por descompressão provocada pelo aliviar da pressão/peso dos sedimentos no decurso do processo de exumação/desgaste/erosão. Uma outra metáfora para ilustrar este movimento é uma esponja do banho que se mantém pressionada na mão e que quando libertada, sorve a água em redor e expande-se. Acontece que a esponja tem um comportamento plástico, comprime-se e expande-se sem romper a sua estrutura, já a rocha tem um comportamento frágil, ou seja, é dura e esses movimentos têm tendência a quebrá-la por serem superiores às tensões que pode suportar.

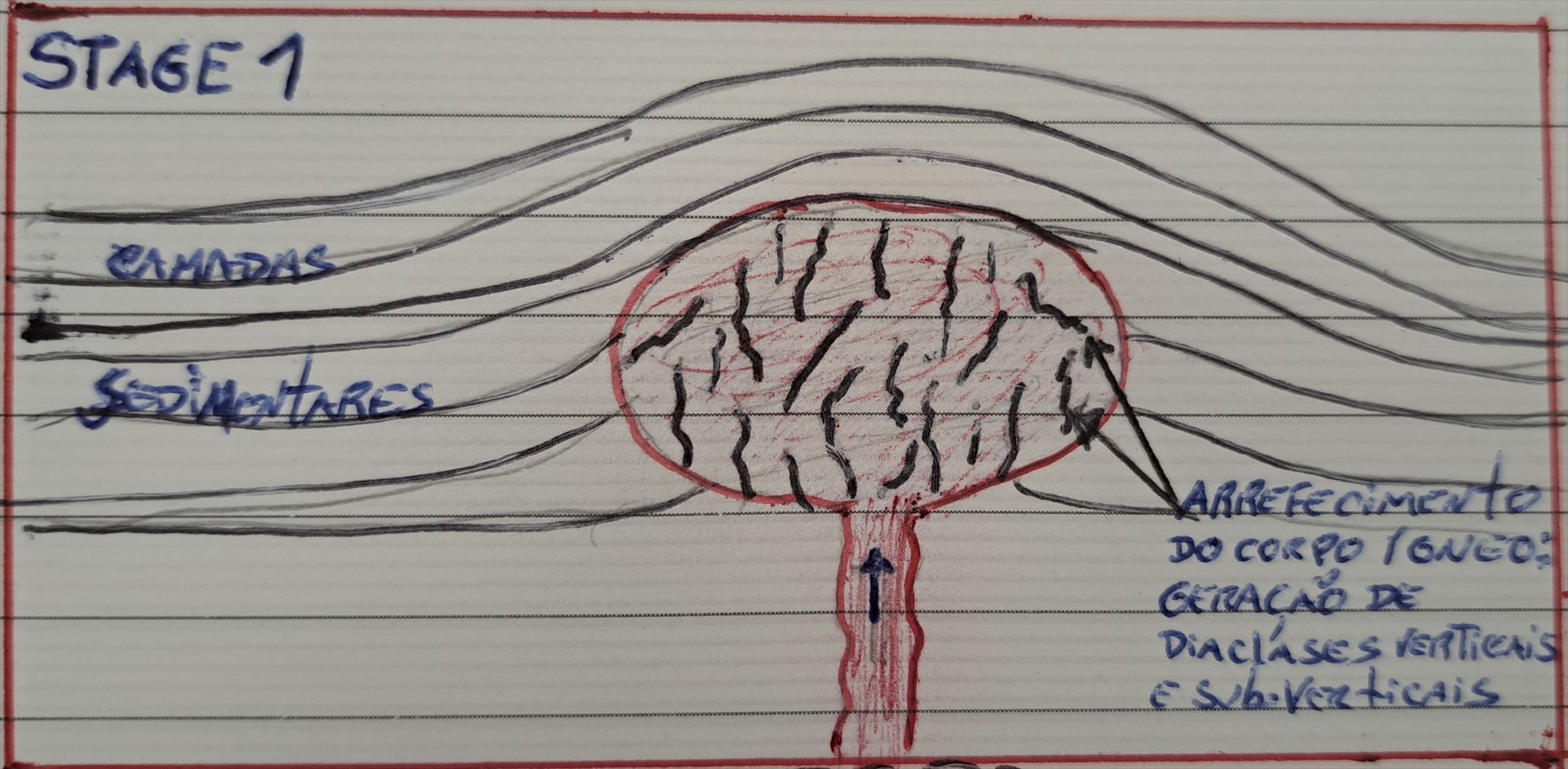

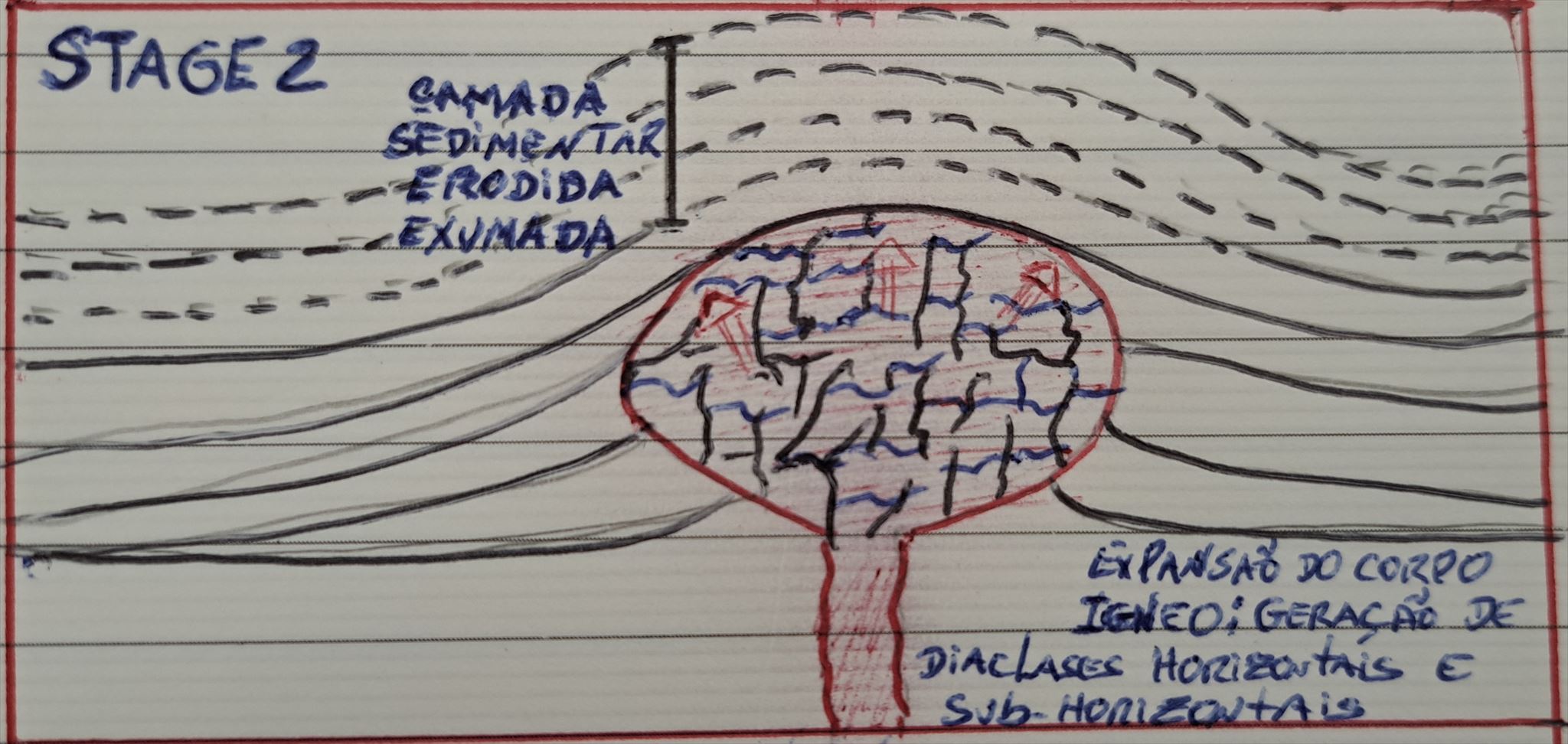

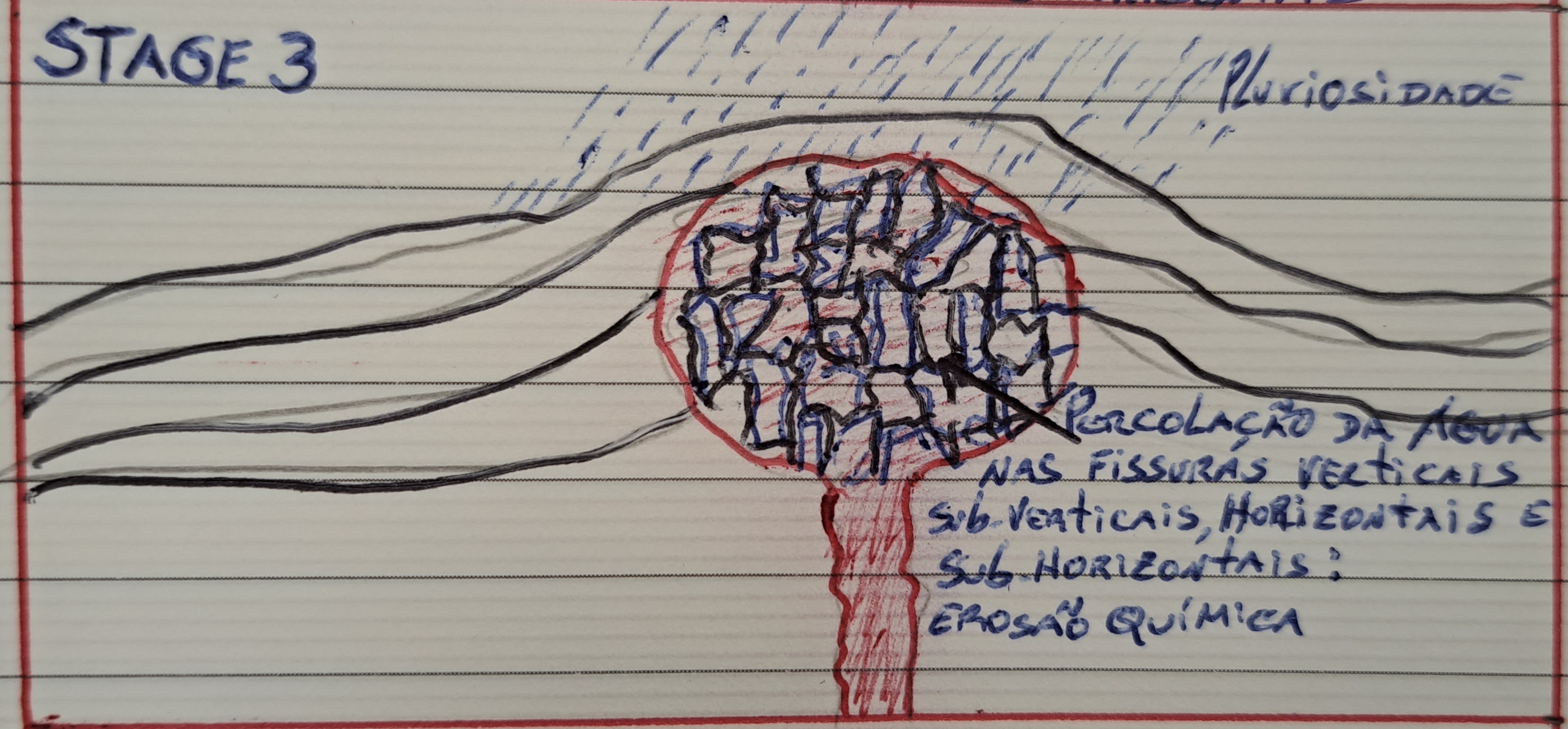

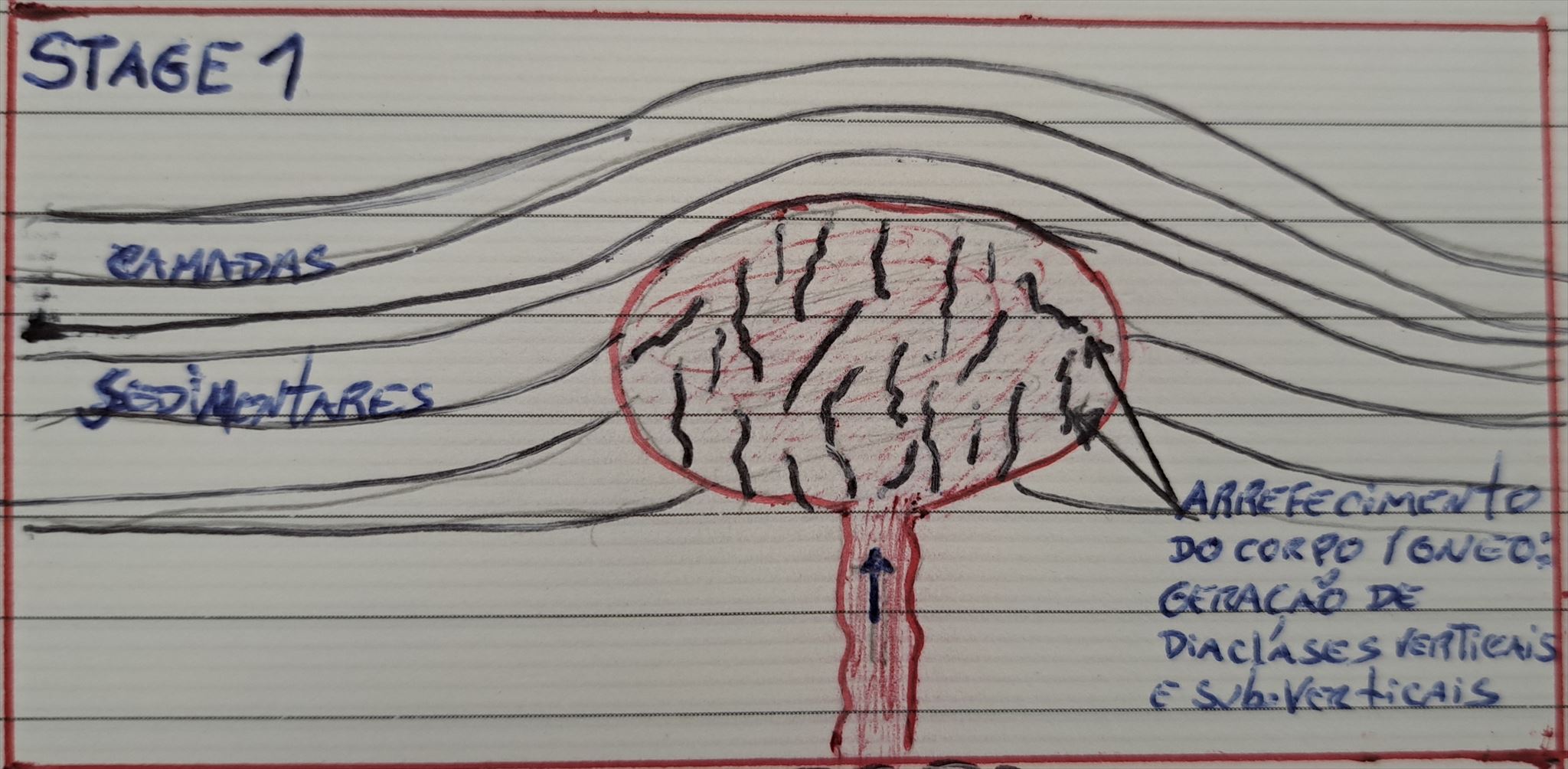

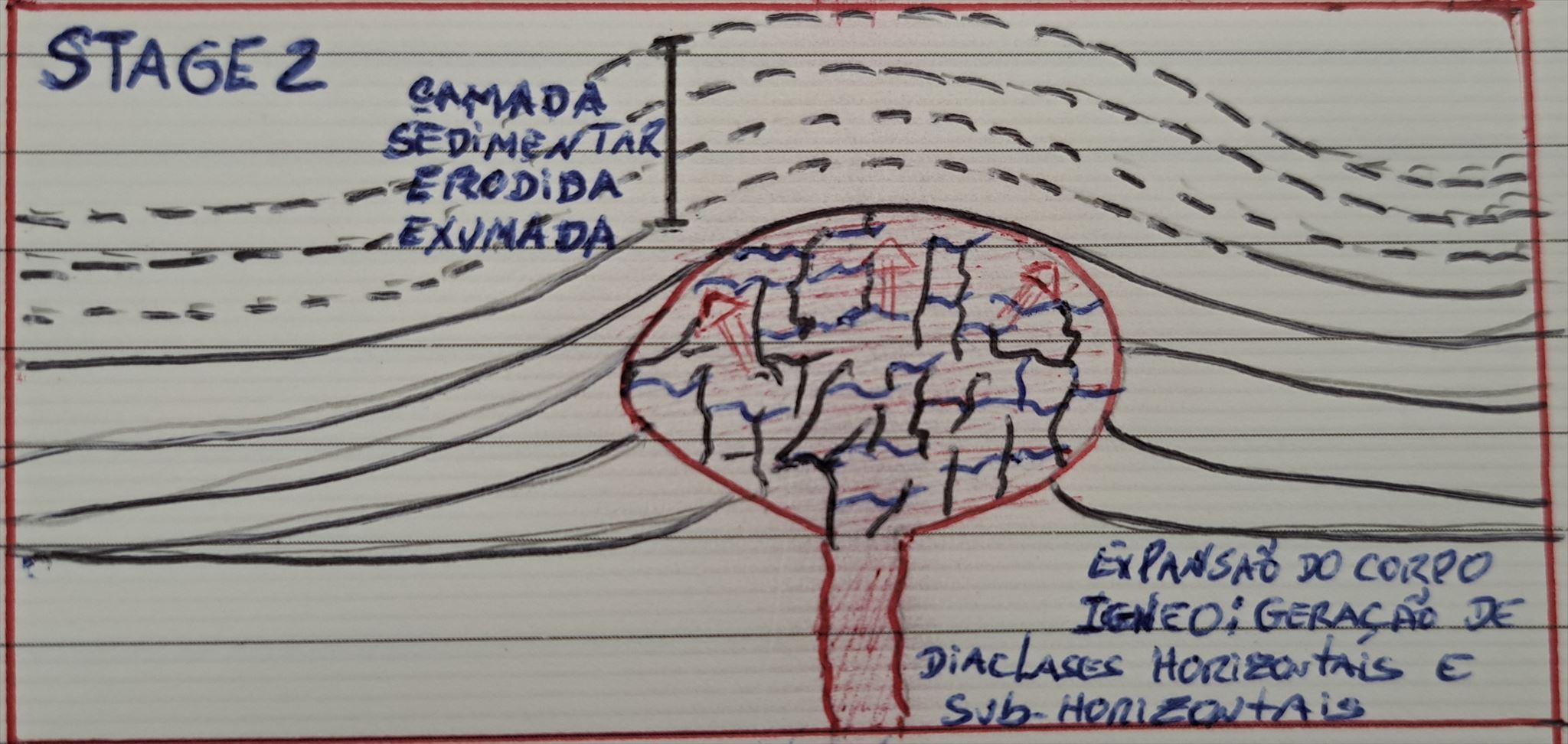

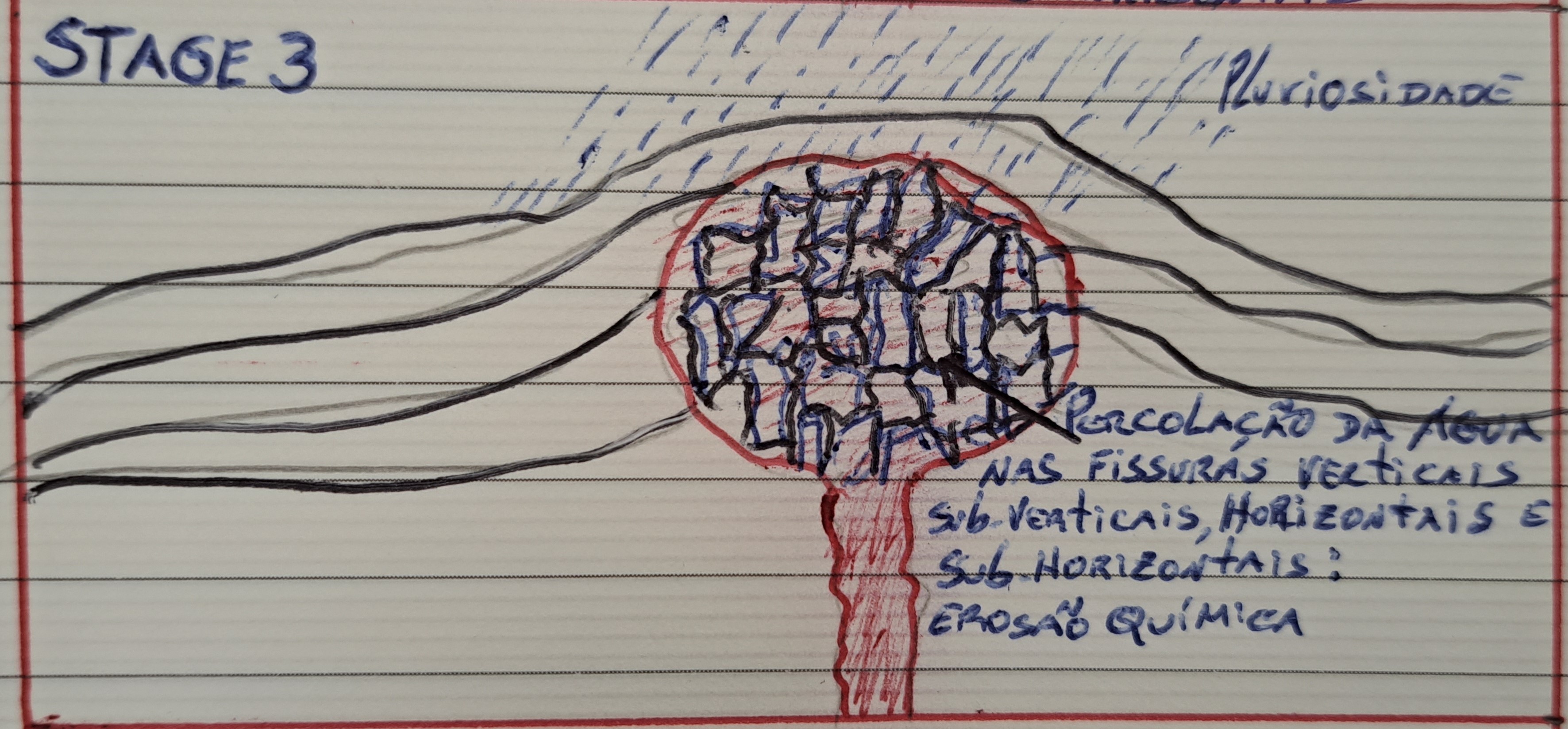

Para ilustrar a formação de um TOR podemos conceber 4 estádios e recorrer a um grafismo, embora tosco, para entender cada um desses estágios:

Estágio 1: O corpo ígneo intrusivo super aquecido empurra a camada sedimentar e arrefece no seu interior. A contração térmica devida ao seu arrefecimento via gerar um comportamento frágil ocorrendo fissuras (diáclases) verticais e sub-verticais.

Estágio 2: A camada sedimentar vai sendo erodida/exumada e a ocorrência da diminuição da pressão/peso dos sedimentos sobre o corpo ígneo vai provocar a sua distensão e, num mesmo comportamento frágil, ocorrem fissuras horizontais e sub horizontais.

Estágio 3: A pluviosidade provoca a infiltração da água na rede de diáclases verticais, sub verticais, horizontais e sub horizontais, promovendo o seu alargamento e espaçamento por erosão química.

Estágio 4: Após total exumação da camada sedimentar resulta a formação do TOR como um modelado granitoide desgastado, preferencialemente, na rede/malha de diáclases verticais, sub verticais, horizontais e sub horizontais e cuja geometria ocorre como um empilhamento desordenado em forma de paralelipípedos.

Se preferires podes ver aqui uma animação mais refinada relativa à formação de Tors: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1nNG6g5ZFiY&pp=ugMICgJlbhABGAE%3D

Fontes:

- Wikipedia (https://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anta_de_Adrenunes)

- https://serradesintra.net/adrenunes/

- TWIDALE, C. R.1 and BOURNE, J. A., Caves in granitic rocks: types, terminology and origins

- https://www.britannica.com/science/tor-geology

The Earthcache is about Igneous Geoforms that occur in intrusive and extrusive rocks. The classification takes as variables the ways and process of the intrusion and extrusion, as well as the weathering process to which they are submitted. This Earthcache is about igneous Geoforms that occur in intrusive igneous rocks (in this area, mainly, Syenites) displaying some features capable to apply for a TOR .

Kindly return via email from my profile with the answers to the two mandatory questions. In order to fully comply with the requirements for a well-received log, please upload a photo in your found log that provide evidence of your observation.

Q1: From where you are standing, how would you describe the igneous outcrop?

a) There are no rounded spherical boulders, but clear evidence of parallelepipeds with the boulders displaying sharp and clear edges.

b) There are already some spherical, but also paralleled shaped boulders some standing vertically, others overturned horizontally and others inclined (sub-horizontal and sub-vertical).

Q2: Is it plausible, from your point of view, to argue for existence of a Talus cave?

Q3: (optional) An anthropic monument or a natural monument? you may freely share the arguments that justify your choice. If you prefer, you can share with the community in your found log.

To prove that it is a megalithic monument, there would be the need for a field survey that would result in the discovery of artefacts. The field research was carried out. However, returning any artefact proving its funerary use. Despite not fulfilling this mandatory epistemological requirement, its classification as a cultural monument persists (Decree Law nr. 136 of 06/16/1910).

In Serra de Sintra, however, there are numerous "cavities, caves, shelters" (GC3VNCX; GC80JY9; GC1H9V2), which may resemble a dolmen or some sort of antropic shelter, but this are natural phenomena of dismantling, rolling or overturning of rock segments caused by weathering or the “process of decomposition or disintegration of rocks and soils (and their constituent minerals) by the action of chemical, physical and biological effects” (in Wikipedia). In fact, this phenomenon of dismantling, rolling, overturning of boulders that sometimes tend to create spacing in the process, creating cavities or caves in between, has a name - Talus (listing img 1) and it is a typical morphological arrangement of igneous plutons such as the Sintra mountain range.

The rock now exposed comes from the upper mantle. It was a superheated rock that, upon rising, cooled and broke up, forming numerous fissures in a network, like a grid. A metaphor to illustrate this phenomenon is like pouring hot water into a cold glass: the sharp contrast in temperature results in the glass breaking into countless cracks. It is the case here! These fissures are weaknesses that expose the integrity of the rock to erosive agents such as rain, river and wind erosion.

When the cracks are presented in a mesh, like a net (as can be seen in many outcrops in the Sintra eruptive massif!), erosion tends to affect the vertices of this mesh first. As a consequence, these outcrops appear as boulders with rounded edges and a spheroid or oval shape, stacked haphazardly on top of each other forming what is called in a free translation "boulder chaos" (listing img 2).

In this specific location, however, the morphology of the boulders does not appear to be a typical boulder chaos 8with its typically spheroid boulders: here the rock carving occurs in the same cracks in a network, but in a geometry that is more reminiscent of parallelepipeds. This happens because its erosion was mainly caused by the percolation of water in its mesh of fissures. This weathering, both chemical and mechanical (caused by the alternation of water in the liquid state and solid state, which increases its volume by 9%), occurred while the rock was not yet exhumed (uncovered), so abrasion agents such as wind and river energy, as well as bio-erosion (themselves surface erosion factors), had less time to manifest themselves, rounding the edges, where this erosion normally occurs first. Thus, when they are exposed by erosive agents in depth and before they are uncovered, their wear accompanies the network of vertical and horizontal weaknesses, that is, they act in the mesh of existing cracks. With time and the widening of these fissures, the blocks end up isolated, and dispersed: sometimes precariously remaining in a horizontal position, other times also occurring very precariously stacked vertically one on top of the other, other times still overturned on top of each other by lack of support, but always maintaining some symmetry, looking more like someone thrown disorderly, the pieces of a domino on the surface.

Depending on their morphology, this is how igneous models are classified: in this specific spot, in Geology, one may consider to classify this geoform as a TOR (listing img 3) because, unlike a chaos of spheroid blocks, it more resembles symmetrical dominoes thrown indifferently to the ground and that are organized in a chaotic way in piles, overturns and boulder slides.

If, from a monumental point of view, this apparent symmetry is sufficient for its anthropic classification, there may be little consensus. From a geological point of view, however, it is a curious place due to the common, but somewhat unprecedented, demonstration of the forms of erosion that affect the granitoids, sometimes in curious modulations.

How do they form?

Its formation stems from weathering processes (wear, erosion) that more easily affect the fissures of the rock in question. These cracks normally occur in a mesh or network geometry, appearing vertically and horizontally (listing img 4).

- the vertical and sub-vertical cracks occur by THERMOCLASTY that is, by the recurrent temperature variation that promotes the thermal expansion/contraction of the igneous body and subsequent fissures (agsin the metaphor of what happens when you put ice water in a heated glass and it breaks into innumerable vertical and sub-vertical fissures).

- horizontal or sub-horizontal cracks occur due to decompression caused by the relief of pressure/weight of the sediments during the exhumation/wear/erosion process. Another metaphor to illustrate this movement is a bath sponge that is kept pressed in the hand and that, when released, absorbs the surrounding water and expands. It turns out that the sponge has a plastic behavior, compresses and expands without breaking its inner structure, whereas the rock has a fragile behavior, that is, it is hard and these movements tend to break it because they are greater than the tensions that can stand.

To illustrate the formation of a TOR, we can conceive of 4 stages and resort to graphics, albeit crude, to understand each of these stages:

Stage 1: The superheated intrusive igneous body pushes the sedimentary layer and cools inside. The thermal contraction due to its cooling generates a brittle behavior with vertical and sub-vertical fissures.

Stage 2: The sedimentary layer is being eroded/exhumed and the occurrence of a decrease in pressure/weight of the sediments on the igneous body will cause its distension and, in the same fragile behavior, horizontal and sub horizontal fissures occur.

Stage 2: The sedimentary layer is being eroded/exhumed and the occurrence of a decrease in pressure/weight of the sediments on the igneous body will cause its distension and, in the same fragile behavior, horizontal and sub horizontal fissures occur.

Stage 3: Rainfall causes water to infiltrate the network of vertical, subvertical, horizontal and sub horizontal joints, promoting their widening and spacing by chemical erosion.

Stage 4: After total exhumation of the sedimentary layer results in the formation of the TOR as a worn granitoid pattern, preferably in the network/mesh of vertical, subvertical, horizontal and sub horizontal diaclases and whose geometry occurs as a disorderly stacking in the form of parallelepipeds.

If you prefer, you can see a more refined animation about the formation of Tors here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1nNG6g5ZFiY&pp=ugMICgJlbhABGAE%3D

Sources:

- Wikipedia (https://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anta_de_Adrenunes)

- https://serradesintra.net/adrenunes/

- TWIDALE, C. R.1 and BOURNE, J. A., Caves in granitic rocks: types, terminology and origins

- https://www.britannica.com/science/tor-geology