Exudation Quartz

In igneous rocks, quartz forms as magma cools. Like water turning into ice, silicon dioxide will crystallize as it cools. Slow cooling generally allows the crystals to grow larger.

Quartz that grows from silica-rich water forms in a similar way. Silicon dioxide dissolves in water, like sugar in tea, but only at high temperature and pressure. Then, when the temperature or pressure drops, the solution becomes saturated, so quartz crystals form.

It is also widespread in metamorphic rocks because in relatively pure form it is not afraid of alteration, high temperature, and high pressure. sandstone becomes quartzite in the course of metamorphism. This is in stark contrast to pelitic (clay-rich) rocks which go through very complicated series of mineral reactions.

Quartz is also the most important hydrothermal mineral, filling cracks in the crust with many other and often economically important minerals.

In practical terms this EarthCache will show you a rock sequence that has “sweated” quartz because of the intense deformation the region has undergone. These are aligned in (white coloured) parallel veins.

Pulo do Lobo

Pulo do Lobo is a waterfall 17 km north of Mértola, in the Lower Alentejo region of Portugal. It is the highest waterfall in Southern Portugal. Its name means "wolf's leap" in English; it was said that only a brave man or a wild animal when chased could leap over the gorge that was created by the waterfall.

Geological setting

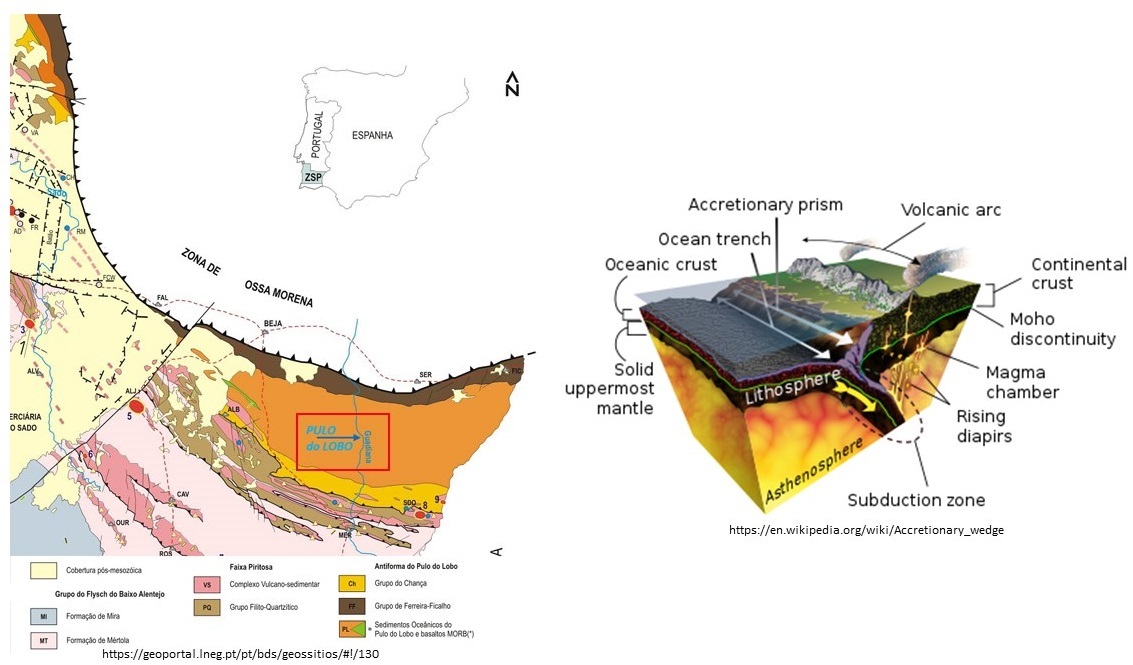

The Pulo do Lobo Formation constitutes the central part of the tectono-stratigraphic unit of the Pulo do Lobo Domain. It is an antiform structure composed of several detrital formations. On the northern flank of the structure, three lithostratigraphic units were described that constitute the Ferreira-Ficalho Group, thus composed, from the base to the top, by the Ribeira de Limas Fm. (Frasnian), Santa Iria Fm. (Famennian) and Horta da Torre Fm. (Famennian) (Carvalho et al., 1976; Oliveira et al., 1986; Giese et al., 1988; Oliveira, 1990; Eden, 1991; Pereira et al., 2006; Pereira et al., 2018). On the southern edge of the antiform, the detrital succession of the Chança Group, which comprises the Atalaia and Gafo Formations, outcrops (Oliveira, 1990; Silva et al., 1990; Oliveira et al., 2019).

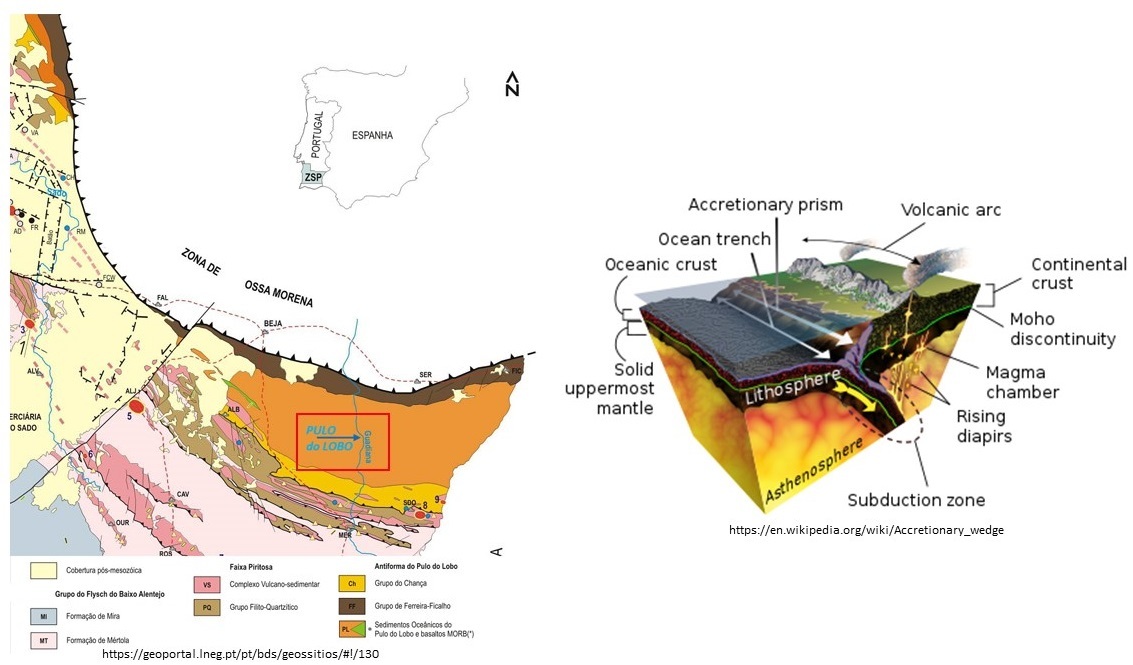

The stratigraphic sequence of the Pulo do Lobo antiform has been interpreted by several authors as the result of an accretionary prism associated with the subduction of an ocean floor beneath the continental crust of the Ossa Morena Zone.

In the Pulo do Lobo waterfall region, the PLF comprises shales, siltstones and quartzites that are highly deformed. The cascade shows the lithological control of quartzite levels, less susceptible to erosion phenomena, compared to schist and siltstone levels. The occurrence of metamorphic exudation quartz is one of the characteristics of this formation (Oliveira, 1990). Structural aspects can be observed all over the geosite area, as this unit is affected by three episodes of tectonic deformation, with associated folding and cleavages. The second episode is the most important and the most visible in several outcrops and is marked by tight folds in the NW-SE direction and strong cleavage to SW, often showing the shear component (Oliveira et al., 2019). The metamorphism in this region is found in the interval from the upper greenschist facies to the lower amphibolite facies (Munhá, 1983; Eden, 1991). In Portugal, south of the Serpa region, this formation was dated using palynology in the Middle Frasnian BM biozone (Pereira et al., 2018).

Validating your find in this EC:

At the posted coordinates look for the quartz, which is easily identifiable as the white “ribbons” in the brown coloured rock. After identifying, answer the following questions:

- Are the quartz veins uniform in thickness? (Yes/No)

- What is the general orientation of the quartz veins (use cardinal or ordinal directions)

- Are they straight lines or do they vary direction? Please justify your answer.

- Look for folds in the rock. A) What is their orientation? B) Do the quartz veins follow the fold or do they cut across the fold?

- Take NON-SPOILER pictures and add them to the log.

Quartzo de Exudação

Em rochas ígneas, o quartzo se forma à medida que o magma arrefece. Como a água se transforma em gelo, o dióxido de silício se cristaliza à medida que a temperatura baixa. O arrefecimento lento geralmente permite que os cristais fiquem maiores.

O quartzo que cresce a partir de água rica em sílica forma-se de maneira semelhante. O dióxido de silício dissolve-se na água, como o açúcar no chá, mas apenas em alta temperatura e pressão. Então, quando a temperatura ou pressão cai, a solução fica saturada, formando cristais de quartzo.

Também é comum em rochas metamórficas porque na sua forma relativamente pura não tem “medo” de alteração, alta temperatura e alta pressão. arenito torna-se quartzito no decurso do metamorfismo. Isso contrasta fortemente com as rochas pelíticas (ricas em argila), que passam por uma série muito complicada de reações minerais.

O quartzo também é o mineral hidrotermal mais importante, preenchendo as fracturas na crusta com muitos outros minerais, muitas vezes economicamente importantes.

Em termos práticos, esta EarthCache vai-te mostrar uma sequência de rochas que “suou” o quartzo por causa da intensa deformação pela qual a região sofreu. Estes são alinhados em veios paralelas (de cor branca).

Pulo do Lobo

Neste setor do seu curso, o rio Guadiana esculpiu um largo desfiladeiro e apresenta um caso excecionalmente homogéneo e bem preservado de um terraço com cerca de 40 km de comprimento e 300 m de largura máxima. A montante da queda de água, o nível de erosão lateral forma um leito de rio inundado, ou faixa submersa, que se eleva gradualmente desenvolvendo-se uma planície de inundação ativa. A transição entre estes dois domínios faz-se pela queda de água de 15 m a partir da qual o rio escavou um canhão interno com a formação de um terraço de cada um dos lados. Este encaixe do rio é evidência do último periodo glaciário onde o nível médio das águas do mar se encontrava 60 m a 140 m abaixo do nível atual (Becerril et al., 2018). Este local evidencia deste modo a última etapa de incisão do Rio Guadiana a partir de um terraço rochoso excecionalmente bem conservado.

Enquadramento Geológico

A sequência estratigráfica da antiforma do Pulo do Lobo tem sido interpretada por vários autores como o resultado de um prisma acrecionário associado à subducção de um fundo oceânico sob a crosta continental da Zona de Ossa Morena.

Na região da Cascata do Pulo do Lobo a FPL compreende xistos, siltitos e quartzitos bastante deformados. A cascata evidencia o controlo litológico dos níveis de quartzito, menos suscetíveis a fenómenos de erosão, face aos níveis de xistos e siltitos. A ocorrência de quartzo de exsudação metamórfica é uma das características desta formação (Oliveira, 1990). Aspetos estruturais podem ser observados um pouco por toda a área do geossítio, uma vez que esta unidade é afetada por três episódios de deformação tectónica, com dobramento e clivagens associadas. O segundo episódio é o mais importante e o mais visível em diversos afloramentos e é marcado por dobramentos apertados de direção NW-SE e forte clivagem vergente para SW, frequentemente mostrando a componente de cisalhamento (Oliveira et al., 2019). O metamorfismo nesta região encontra-se no intervalo desde a fácies superior dos xistos verdes, à inferior da anfibolítica (Munhá, 1983; Eden, 1991). Em Portugal, a sul da região de Serpa, esta formação foi datada com recurso a palinologia na biozona BM do Frasniano Médio (Pereira et al., 2018).

Validar o registo nesta EC:

Nas coordenadas da cache, procura o quartzo, que é facilmente identificável como as “fitas” brancas na rocha de cor castanha. Depois de as identificar, responde às seguintes perguntas:

- Os veios de quartzo são uniformes em espessura? (Sim/Não)

- Qual é a orientação geral dos veios de quartzo (usa as direções cardinais ou ordinais)

- Em relação ao rio, estas estão paralelas ou a ângulos rectos do mesmo?

- São linhas rectas ou variam? (Justifica a tua resposta)

- Procura dobras na rocha. A) Qual é a sua orientação? B) Os veios de quartzo seguem a dobra ou cortam a dobra?

- Tire fotos que NÃO SEJAM SPOILER e adiciona-as ao registo.

Refs:

Burlini, L., and Bruhn, D (2005) High-strain zones: laboratory perspectives on strain softening during ductile deformation. Geological Society London Special Publications 245(1):1-24

https://www.sandatlas.org/quartz/

Okazaki, K., Burdette, E., Hirth, G. (2019) Rheology of the fluid oversaturated quartz shear zone at the brittle-ductile transition. American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting 2019, abstract #T54C-08

Spur, J. E. (1905) Geology of the Tonopah Mining District, Nevada. Professional Paper, United States Geological Survey

Carvalho D., Correia M. & Inverno C. (1976) <Contribuição para o conhecimento geológico do Grupo Ferreira-Ficalho. Suas relações com a Faixa Piritosa e o Grupo do Pulo do Lobo> Memórias e Notícias do Museu de Mineralogia e Geologia da Universidade de Coimbra. Vol. 82 p. 145-169

Eden, C. P. (1991) <Tectonostratigraphic analysis of the Northern Extent of the Oceanic Exotic Terrane, Northwestern Huelva Province, Spain> Ph.D. Thesis, Univ. Southampton. 281 pp.

Giese Y., Reitz E. & Walter R. (1988) <Contributions to the stratigraphy of the Pulo do Lobo succession in Southwest Spain> Comissão dos Serviços Geológicos de Portugal, Lisboa. Vol. 74 p. 79-84

Munhá J. M. (1983) <Low grade metamorphism in the Iberian Pyrite Belt Pyrite> Comissão dos Serviços Geológicos de Portugal, Lisboa. Vol. 69 p. 3-35

Oliveira J. T., Cunha T. A., Streel M. & Vanguestaine M. (1986) <Dating the Horta da Torre Fm., a new lithostratigraphic unit of the Ferreira-Ficalho Group, South Portuguese Zone: Geological consequences> Comunicações dos Serviços Geológicos de Portugal, Lisboa. Vol. 72 (1/2) p. 129-135

Oliveira J. T. (1990) <Stratigraphy and syn-sedimentary tectonism in the South Portuguese Zone> Dallmeyer R. D., Martínez García E. (eds), Pre-Mesozoic Geology of Iberia. Springer Verlag. p. 334-347

Oliveira, J. T., Relvas, J. M. R. S., Pereira, Z., Matos, J. X., Rosa, C. J. & Rosa, D. (2006) <O Complexo Vulcano-Sedimentar da Faixa Piritosa: estratigrafia, vulcanismo, mineralizações associadas e evolução tectonoestratigráfica no contexto da Zona Sul Portuguesa> Eds: R. Dias, A. Araújo, P. Terrinha, & J.C. Kullberg (Eds.), Geologia de Portugal no Contexto da Ibéria. Univ. Évora, Portugal: VII Cong. Nac. Geologia. p. 207-244

Oliveira J. T., Quesada C., Pereira Z., Matos J. X., Solá A. R., Rosa D., Albardeiro L., Díez-Montes A., Morais I., Inverno C., Rosa C. & Relvas J. (2019) <South Portuguese Terrane: A Continental Affinity Exotic Unit> Quesada, C., Oliveira J. T. (Eds.), The Geology of Iberia: A Geodynamic Approach, Regional Geology Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-10519-8_6. p. 173-206

Ortega-Becerril J. A., Garzón G., Tejero R., Meriaux A. S., Delunel R., Merchel S. & Rugel G. (2018) <Controls on strath terrace formation and evolution: The lower Guadiana River, Pulo do Lobo, Portugal> Geomorphology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2018.07.015. Vol. 319 p. 62-77

Pereira, Z., Fernandes, P., Oliveira, J. T. (2006) <Palinoestratigrafia do Domínio Pulo do Lobo, Zona Sul Portuguesa> Comunicações Geológicas. Tomo 93 p. 23-38

Pereira Z., Fernandes P., Matos J., Oliveira J. T. & Jorge R. S. (2018) <Stratigraphy of the Northern Pulo do Lobo Domain, SW Iberia Variscides: a palynological contribution> Geobios. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geobios.2018.04.001.

Silva, J. B., Oliveira, J. T. & Ribeiro, A. (1990) <South Portuguese Zone. Structural outline> Dallmeyer R. D., Martínez García E. (eds), Pre-Mesozoic Geology of Iberia. Springer Verlag. p. 348-362

https://geoportal.lneg.pt/pt/bds/geossitios/#!/130

The most exciting way to learn about the Earth and its processes is to get into the outdoors and experience it first-hand. Visiting an Earthcache is a great outdoor activity the whole family can enjoy.

The most exciting way to learn about the Earth and its processes is to get into the outdoors and experience it first-hand. Visiting an Earthcache is a great outdoor activity the whole family can enjoy.

An Earthcache is a special place that people can visit to learn about a unique geoscience feature or aspect of our Earth. Earthcaches include a set of educational notes and the details about where to find the location (latitude and longitude). Visitors to Earthcaches can see how our planet has been shaped by geological processes, how we manage the resources and how scientists gather evidence to learn about the Earth. To find out more click HERE.