Clarke's Gap Bridge is one of the few surviving structures constructed from building stones of Virginia diabase. To access the Earthcache, park at the listed parking waypoint and follow the switchback turn down to the main W&OD trail. Turn right and walk a short distance. With the recent re-routing of the W&OD trail, the switchback is less used, but the main trail remains busy. Please walk only on the right hand edge of the trail. Cyclists will commonly call out "On your left", meaning they are passing you towards the middle of the trail and you should remain on the right hand edge. Permission for this Earthcache was generously granted by the Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority and, as with all NVRPA parks, this cache is only available during daylight hours.

The Clarke's Gap Bridge was constructed in the 1870's as the Washington and Old Dominion Railroad was extended westward. Today, Dry Mill Road crosses over the bridge. The stone guardrails topping the bridge were added later and appear to be local field stones. The stone that makes up the Clarke's Gap archway was quarried along Goose Creek near what is today Ashburn, VA. These quarries supplied stone for a number of structures in Leesburg including Carlheim (also called Paxton Manor), which was constructed in 1872.

Diabase occurs in Virginia in a series of NE to SW trending basins that formed as rifting began to form the Atlantic Ocean during the Triassic period. Within these basins, magmas were emplaced and cooled to produce exceptionally fine-grained (aphanitic) basalt to coarser-grained gabbros. Collectively, these rocks are termed diabase. In Loudon County, most diabase is quarried as crushed stone for road construction, building foundations, or for mixing in concrete. In 2006, Loudon County produced almost 10 million tons of crushed diabase for construction projects in the greater DC area, with a value in excess of $100 million. An excellent view of the quarries and explanation is given by "Quarry Overlook Earth Cache" (GC2AJ1D).

Despite the abundance of diabase available along Goose Creek, relatively little was used for building stone (dimension stone, as it's called in the quarrying trade, which is used for monuments, building stones, countertops, and headstones, among others). In 1928, Joseph K. Roberts in "The Geology of the Virginia Triassic" wrote that diabase was seldom used because of the preferred use of concrete, the fact that the major quarries for diabase opened after the popularity of building stone had decreased, and the dark coloration made it unfavorable. He noted that medium-grained, lighter-colored diabase was the most popular building stone "... and the fine to dense rocks will never be popular." As it turned out, he was wrong. Nearly a centruy later, fine-grained Virginia diabase is a popular stone for monuments. In 2006, quarries in Culpeper Country produced about 16,000 tons of diabase for use as dimension stone.

What's in a name?

Today, Virginia diabase marketed as dimension stone comes primarily from quarries in southern Culpeper County near Rapidan, VA. This material is sometimes marketed as Virginia Black Granite. If you've ever had the experience of purchasing stones countertops for your kitchen, you were probably presented with a wide variety of "granite", most of which weren't actually granite. To geologists, granite has a very distinctive mineralogy and chemistry. Let's take a minute to learn a bit more.

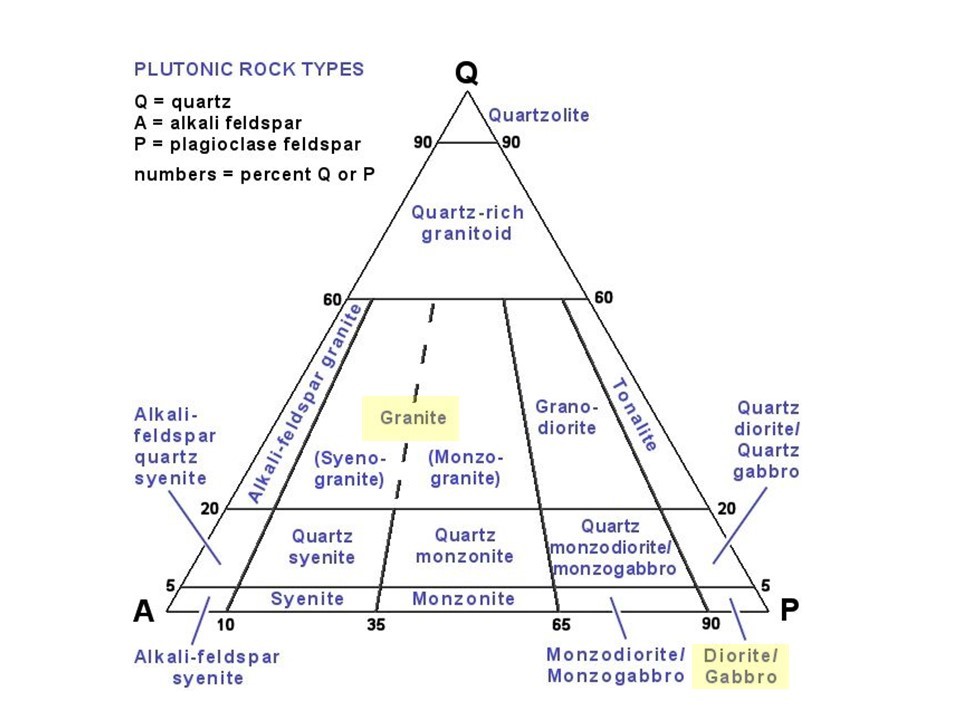

For igneous rocks that have mineral grains large enough to see individual grains, the name of the rock can be determined from the abundance of the different minerals. A QAPF diagram plots different kinds of rocks in terms of their abundance of quartz (Q), alkali feldspars (A), plagioclase (P) and feldspathoids (F). Below is the QAP portion of this diagram with the fields for diabase (labeled by the synonyms gabbro/diorite) and granite highlighted.

An easy way to tell diabase from granite is to look at the light-colored mineral grains. Plagioclase is typically white in color, while alkali feldspar is typically salmon-colored. The lighter colored grains in diabase should be dominantly white plagioclase, while granite should contain roughly equal amounts of white and salmon-colored grains.

Question 1: On the SE side of the bridge, fresher surfaces of the rock are exposed. Can you distinguish individual grains of minerals? If so, are all the light-colored grains you observe white or are some salmon-colored? From your own observations, would you describe this rock as granite? Why or why not?

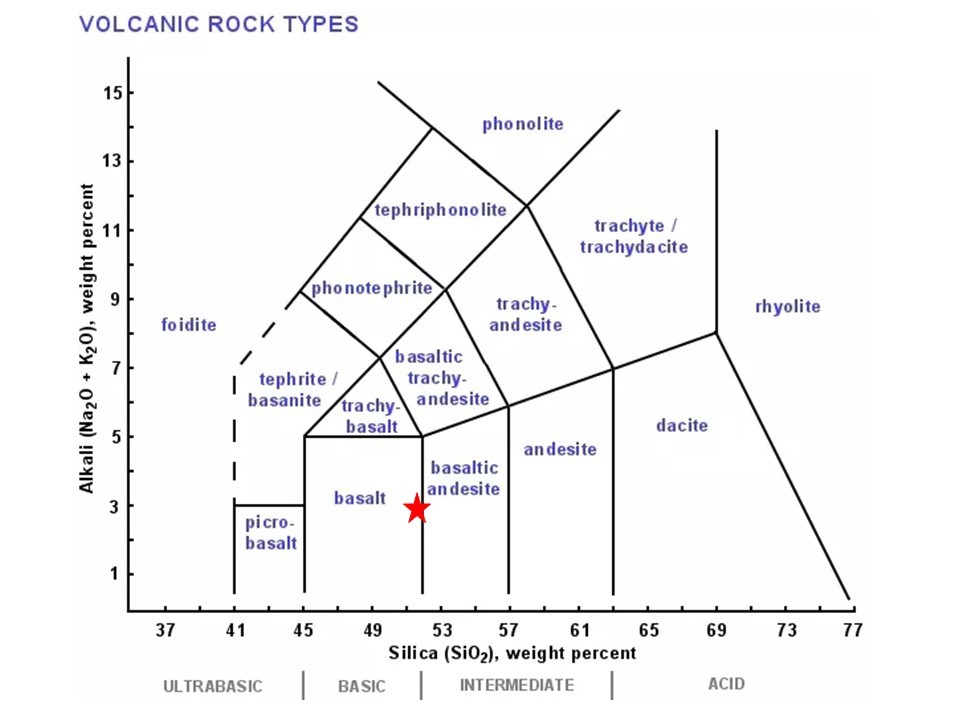

Igneous rocks can be also classified using their chemical composition. A TAS diagram, which plots total alkalis (TA), including sodium and potassium as oxides, vs silica (S) as SiO2 is a useful diagram. This diagram is designed for volcanic rocks where individual minerals cannot be distinguished. As such, the intrusive rock diabase is shown as its volcanic equivalent basalt and volcanic rhyolite replaces granite. In fact, some Virginia diabases are so fine-grained that this kind of classification is useful. In 1928, Roberts reported analyses of average diabase from the Goose Creek quarries with 51.56 wt.% SiO2, 2.08 wt.% Na2O, and 0.96 wt.% K2O. When plotted on a TAS diagram, the composition plots within the field of basalts/diabase and far from the more SiO2-rich rhyolite/granite.

Question 2: Based on what you answered in question 1, should these rocks be classified using a QAPF diagram that uses the abundance of minerals or a TAS diagram that uses the chemical composition? Why?

What's in a name? - Part 2

Virginia diabase is often also called traprock. This name comes not because it "traps" anything, like oil, gas, or water, but from the Swedish word "trappa" meaning stairs. Around the world, diabase is often called traprock because successive lava flows produce exposed surfaces that weather to look like flights of stairs. Another possible explanation for the name traprock comes from an unusual feature of diabases like those in Virginia. When diabase cools from a magma, the solid rock occupies less volume than the magma from which it formed. During cooling, the rock fractures producing "joints". Unlike the more familiar faults, joints don't have any offset in the rocks caused by movement along the fracture surface. In diabase, The most spectacular of these joints are columnar joints, such as those at the famous Giant's Causeway along the north coast of Northern Ireland. The columns produced in this manner are much longer than they are wide and their ends are seldom squares or rectangles, but often have 4-6 sides that meet at angles other than 90 degrees.

In his 1928 paper, Roberts noted that joint planes in some of the Virginia diabase made it possible to remove blocks for building stones. In the absence of joint planes, removal of blocks for dimension stone is much more labor intensive. The favored technique used in rocks without joints involves drilling a series of holes - like perforations in a piece of paper - which can then be used with low explosive loads to separate the blocks. This technique is used today in Virginia dimension stone quarrying, as it allows better control of the block size and shape.

Question 3: On the NE and SW sides of the stone arch, look carefully at the building stones. Do you see any evidence in either the shapes of the stones or markings to show whether these stones were separated along existing joints or by drilling and blasting? Which method do you think was used? Why?

Virginia Diabase - Honoring the Heroes

The finest-grained Virginia diabase has become a popular dimension stone for use in monuments. It has been used for construction of the American Veterans Disabled for Life Memorial in Washington, DC, and the Sean Collier Memorial at the Massachussets Institue of Technology in Cambridge, MA, which honors a beloved MIT police officer killed on April 18, 2013, by the Boston Marathon bombers. Perhaps the most famous use of Virginia diabase as a building stone is the National 9/11 Memorial built at Ground Zero in New York City. The stone from Rapidan, VA, used for the National 9/11 memorial exhibits a swirled appearance suggestive of a mist. Tollo et al. (1987) in their "Field Guide to the Igneous Rocks of the Southern Culpeper Basin, Virginia" noted that magma currents during the crystallization and emplacement produced these textures. Virginia diabase is chosen both for its visual qualities and its durability. Memorials are designed to stand the test of time, retaining their sharp edges and names words carved into the stone. Soft stones like sandstone will round at the edges, with the words becoming less distinct and the stones eventually crumbling. A great example of old sandstone monuments in the DC area are the Boundary Stones that mark the original District of Columbia.

Question 4: At nearly 150 years old, the Clarke's Gap stone archway is one of the oldest structures using Virginia diabase. What evidence do you see that might suggest that this is a durable stone appropriate for monuments? Are the exposed edges of stones sharp or rounded? Are there any marks in the stones that have survived 150 years?

LOGGING REQUIREMENTS

After reading the information above, send answers to questions 1-4 to the cache owner:

Question 1: On the SE side of the bridge, fresher surfaces of the rock are exposed. Can you distinguish individual grains of minerals? If so, are all the light-colored grains you observe white or are some salmon-colored? From your own observations, would you describe this rock as granite? Why or why not?

Question 2: Based on what you answered in question 1, should these rocks be classified using a QAPF diagram that uses the abundance of minerals or a TAS diagram that uses the chemical composition? Why?

Question 3: On the NE and SW sides of the stone arch, look carefully at the building stones. Do you see any evidence in either the shapes of the stones or markings to show whether these stones were separated along existing joints or by drilling and blasting? Which method do you think was used? Why?

Question 4: At nearly 150 years old, the Clarke's Gap stone archway is one of the oldest structures using Virginia diabase. What evidence do you see that might suggest that this is a durable stone appropriate for monuments? Are the exposed edges of stones sharp or rounded? Are there any marks in the stones that have survived 150 years?

WITH YOUR LOG, POST A PHOTO. Posting a photo that readily indicates that you (and anyone else logging the find) are at the location. You do not have to show your face, but the photo should be personalized by you or a personal item. Please do not show answers to any of the questions above. NOTE: Per newly published Earthcache guidelines, this requirement is REQUIRED to claim the find.

If responses to the questions above are not received in a reasonable time period, cachers will receive a request for answers. Failure to respond may result in deletion of your log.

BEST EARTHCACHE NOMINEE