Once upon a time . . . a long, long time ago . . . ok, enough of that. Yup, it was a long time ago – Mount Rainier was taller than today, maybe as tall as 15,500 feet. But about 5,600 years ago, she literally lost her top (one source described it as a decapitation!), and reshaped the southern and eastern Puget Sound area into much of what it is today.

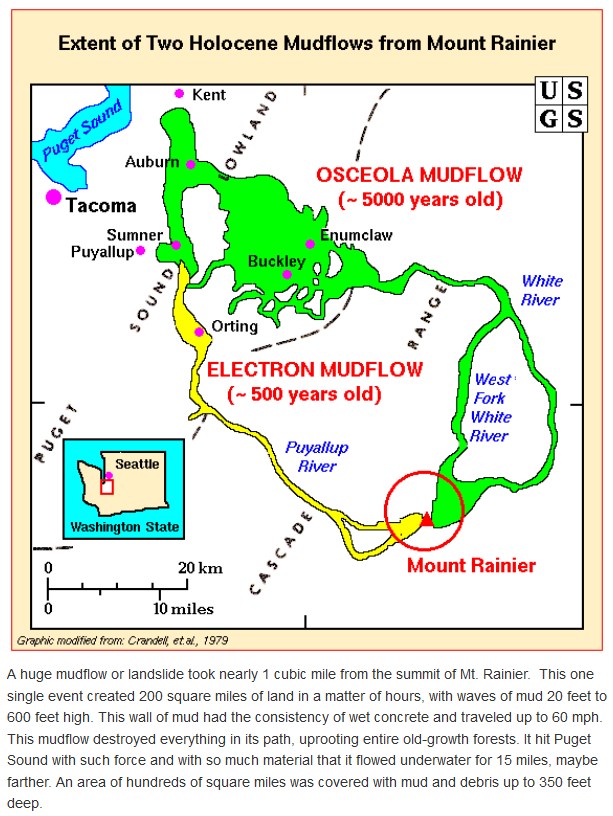

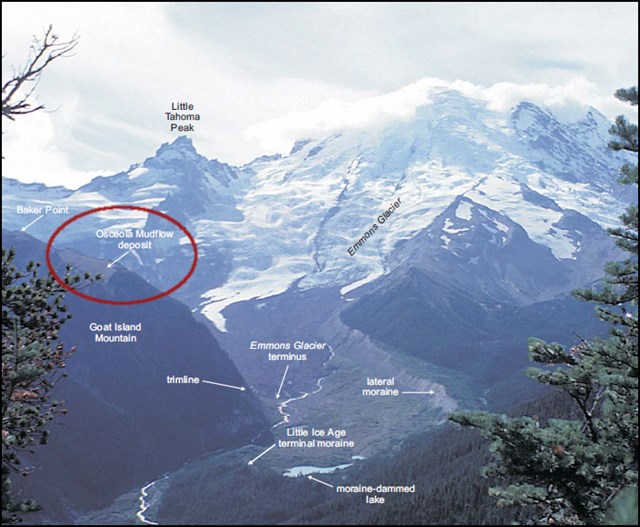

The Osceola Mudflow was the largest mudflow of the post-glacial age at Mount Rainier. This was a catastrophic event, possibly triggered by a small eruption. About one cubic mile of hydrothermally altered rock collapsed as a giant landslide. It took the summit of the mountain, along with part of the northeast flank and the overlying glaciers, racing downwards toward Puget Sound, through the White and Green river valleys, reaching as far as Kent, 70 miles away. Possibly moving as fast as an estimated 45 to 60 miles per hour, it covered 212 square miles with mud, rocks and trees, possibly as deep as 300 feet (one source suggested 600 feet deep!), and destroying everything in its path.

As the mudflow progressed downstream, its content changed. Amounts of sand and gravel increased, while clay content decreased. Sadly, humans were probably impacted. Archeologists have found arrowheads under 75 feet of the deposit near Auburn. Muddy and turbulent floods continued beyond the mudflow, reaching Elliott Bay in Seattle (through the Duwamish River valley) and Commencement Bay in Tacoma. It's hypothesized that when this mudflow hit Puget Sound, it could have traveled underwater for more than 15 miles, maybe further.

Remnants (and I think this is an understatement) of the Osceola Mudflow remain today. The communities of Orting, Buckley, Sumner, Puyallup, Enumclaw, and Auburn are located (some partially) on top of deposits from the mudflow, although some are on top of more recent flows as well. The mudflow added 30 to 100 feet of mostly clay (not so good for farming) to what is known today as the Enumclaw Plateau. Before the mudflow, Puget Sound waters covered what became the Duwamish, Puyallup, and White river valleys. Numerous examples of the mudflow are present as you drive east from Enumclaw. A water supply well drilled at Silver Springs Campground hit the mudflow at about 48 feet, and was still in it when drilling stopped at nearly 200 feet. This mudflow can be seen along the banks of the White River near Greenwater and (obviously) along the road to Sunrise.

So . . . what's the difference between a mudflow and a lahar? None. Technically, mudflow was used before the term lahar. This was indeed a lahar, defined as “a debris flow resulting from an eruption or originating in volcanic deposits.” Lahars are common at Mt. Rainier. Large amounts of snow and ice provide water when melted, and the higher parts of the volcano have an abundance of loose, weak and hydrothermally altered rock. In this case, this alteration occurs when hot, sulfur-rich volcanic gas encounters water. The gases dissolve into the water, creating sulfuric acid that attacks and leaches chemical components from the rock. Often, much of the rock is replaced with weak and water-saturated clay minerals. This helps the collapsed material flow like a liquid.

When it let loose, the Osceola Mudflow left a one mile wide horseshoe-shaped crater, open to the northeast, nearly the same size as the Mount St. Helens crater from its 1980 eruption, although much of the crater created by the Osceola Mudflow has since been filled in by subsequent lava eruptions, the most recent being about 2200 years ago.

About this earthcache:

- There are several wide pull-offs on the downhill side of the road between the initial coordinates given and the earthcache MORA: The War of Fire and Ice further up the road. Any of them will work for this earthcache. Additional coordinates for one are given below.

- Everything is visible from the downhill side. Please do not cross the road to the uphill side. There are no pull-offs on that side, and you could become an unexpected hazard to downhill drivers.

- This site is typically closed by snow during the winter months from mid-October through June.

- The questions to complete this earthcache are below. They are not meant to be difficult.

The questions: From the downhill side of the road, and looking across the road to the uphill side, please consider the following questions. Please email me answers to the questions on the same day that you log your successful find of this earthcache. Do not include the answers in your online log. Online logs without the answers emailed to me on the same day risk deletion. If you are concerned that there could be an issue, save your answers in the "Personal Cache Note" section near the top of the cache page. (That might be good general practice, anyway.)

- How many layers do you see?

- Estimate the depth of the largest layer. This is the mudflow layer.

- As the mudflow progressed toward Puget Sound, what do you think happened to its depth?

- If you were to grab a handful of the dry mudflow (DON'T DO IT!) and get it wet, what do you think might happen?

Resources consulted for this earthcache included:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mount_Rainier

- https://volcanoes.usgs.gov/volcanoes/mount_rainier/geo_hist_lahars.html

- http://www.historylink.org/index.cfm?DisplayPage=output.cfm&file_id=5095

- http://gsabulletin.gsapubs.org/content/109/2/143

- https://commons.wvc.edu/rdawes/virtualfieldsites/Enumclaw/VFSEnumclaw.html

- http://geology.com/usgs/rainier/

- http://www.blackdiamondnow.net/black-diamond-now/2013/05/ever-wonder-why-we-have-the-enumclaw-plateau.html

- Roadside Geology of Mount Rainier National Park and Vicinity by Patrick T. Pringle (pdf)

- Geology Underfoot in Western Washington by Dave Tucker

- Roadside Geology of Washington by David D. Alt and Donald W. Hyndman

2016 was the 100th anniversary of the National Park Service, and to celebrate, Visit Rainier and WSGA hosted the Visit Rainier Centennial GeoTour - 100 caches placed in and around Mount Rainier National Park. The geocaches highlighted the rich history, scenic wonders, quaint communities, and hidden gems of the Rainier region. Participants received geocoin and pathtag prizes for finding all the caches.