For 100 years, the National Park Service has preserved America’s special places “for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future generations.” Celebrate its second century with the Find Your Park GeoTour that launched April 2016 and explore these geocaches placed for you by National Park Service Rangers and their partners.

For 100 years, the National Park Service has preserved America’s special places “for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future generations.” Celebrate its second century with the Find Your Park GeoTour that launched April 2016 and explore these geocaches placed for you by National Park Service Rangers and their partners.

geocaching.com/play/geotours/findyourpark

Like most of the valleys surrounding Mt. Rainier. the Carbon River valley was carved out by glaciers descending from the volcano over many thousands of years. As the ice age waned, the glacier retreated, leaving a typical U-shaped glacial valley. Descending the northern slopes of Mt. Rainier, the Carbon Glacier still remains the longest, thickest, and largest volume glacier in the lower 48-states of the USA.

The glacier is an immense erosion machine, grinding the soft volcanic rock of Mt. Rainier and depositing it at the ends and sides of the glacier as a series of moraines. The U-shaped valley that was left by the retreating glacier didn't last long as the river has started to fill in with sediment carried down the river over the past ten or so millennia. This geological process is called aggradation.

There are several mechanisms for carrying sediment downstream from the glacier's end:

- Rain-induced floods - This area typically gets around 80" of rain per year, making it into a temperate rain forest. On occasion, the weather patterns can result in a tremendous amount of rain falling in a short time. In 2006, 18 inches of rain fell in only 36 hours resulting in tremendous floods all around the park. Damage was widespread throughout the park. It was particularly severe in this area and resulted in the permanent closure of the Carbon River Road.

- Glacial-outburst floods - Upon occasion, the water stored within a glacier can be released quickly due to any number of factors, including warming from the volcano, prolonged heating from a hot temperature spell, or internal collapse of parts of the glacier. This process is also known by the Icelandic word Jökulhlaup. The image below is from a trip the CO made to Iceland where an immense glacial outburst flood occurred in 1996.

This type of flood happens from time to time at Mt. Rainier, most recently in Aug of 2015. This video shows this event, which was actually rather small despite the fact that it easily carried downed timber that was 50 feet long down the river. The Carbon River is susceptible to much larger events than this one.

- Lahars - these mud and debris flows are similar to glacial outburst floods, but it is the volcano itself rather than the glacier that is the source of a lahar. The word "lahar" is from the Indonesian term for mud flows which happen often in that volcano-rich country. The most famous lahar in Washington state were the lahars that flowed down from Mt. St. Helens following its eruption in 1980. The Toutle River valley was inundated many miles downstream from this event.

Mt. Rainier, being a bigger volcano and closer to the population centers of Puget Sound, is actually much more dangerous in this regard. Debris flows from the mountain have reached the Puget Sound lowlands repeatedly, most recently only 500 years ago with the Electron Mud Flow which reached the area where the town of Orting now lies. The image below, taken by geologist Pat Pringle, shows the stump of an old growth Douglas fir that was killed by that mudflow in the Puyallup River Valley. The stump was excavated during the building of a new subdivision.

In order to log this earthcache, please send me (either via Geocaching.com message or email) the answers to the following questions:

- The name of this earthcache and all geocaching.com names of the party for which these answers will apply along with the date of your visit.

- The posted coordinates are in the middle of a bridge across the river. Measure the length of the bridge using your GPS, car odometer, or other technology at your disposal. Estimate what percentage of the bridge width is actually going over water at the time of your visit.

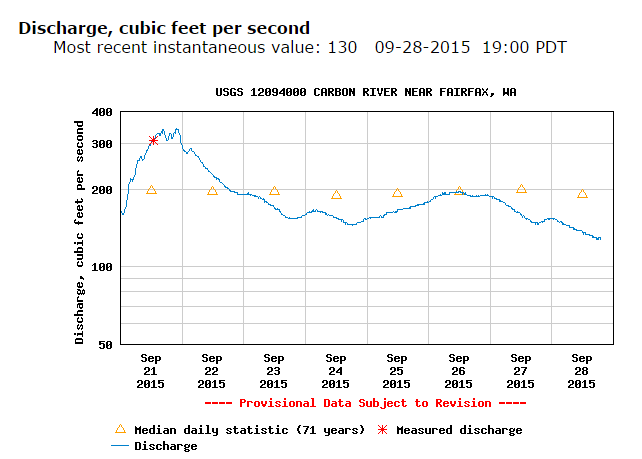

- The USGS has a stream gauge that measures flows in the river a few miles downstream from this spot. Using the link above, report the value of the discharge at the time of your visit (in cubic feet per second) along with the daily median (shown by the orange triangle). An example graph from this station is shown below. For example, on Sept. 21st, the stream flow was about 300 cubic feet per second and the median for Sept. 21st is about 200 cubic feet per second.

- Compare the water flows during your visit to the flows of the Nov. 2006 rainstorm (maximum flow of 14,500 cubic feet per second). Continuing with the example from above, the maximum flows from the Nov. 2006 rainstorm were about 48.3 times more water than on Sept. 21st.

- Make your way down to the stream bed and estimate the size of an average large rock in the stream bed. Guess how much water you think it would take to push this rock down the river. (Note from the CO - you won't be judged on your guess, I would just like you to think about it).

Upon receiving a message or email with good answers for this earthcache, the CO will respond with the password phrase for the Rainier geotour.

References:

The Roadside Geology of Mount Rainier National Park and Vicinity, Patrick Pringle (2008)

The Great Flood of November 2006, National Park Service.

2016 was the 100th anniversary of the National Park Service, and to celebrate, Visit Rainier and WSGA hosted the Visit Rainier Centennial GeoTour - 100 caches placed in and around Mount Rainier National Park. The geocaches highlighted the rich history, scenic wonders, quaint communities, and hidden gems of the Rainier region. Participants received geocoin and pathtag prizes for finding all the caches.