|

Os Açores

Os Açores, oficialmente designados por Região Autónoma dos Açores, são um arquipélago transcontinental e um território autónomo da República Portuguesa, situado no Atlântico nordeste, dotado de autonomia política e administrativa. Situado precisamente sobre a Dorsal Média Atlântica, o arquipélago situa-se no nordeste do Oceano Atlântico entre os 36º e os 43º de latitude Norte e os 25º e os 31º de longitude Oeste. Os territórios mais próximos são a Península Ibérica, a cerca de 2000 km a leste, a Madeira a 1200 km a sueste, a Nova Escócia a 2300 km a noroeste e a Bermuda a 3500 km a sudoeste. Integra a região biogeográfica da Macaronésia.

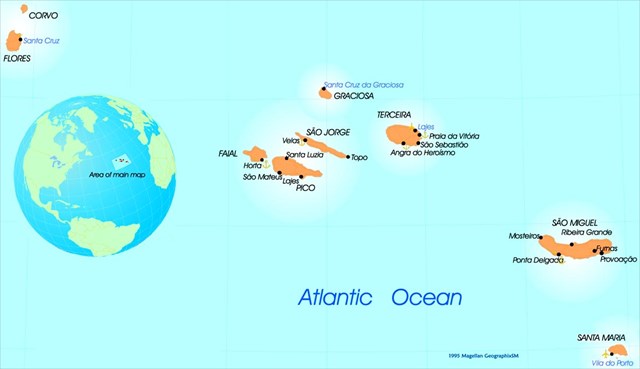

O arquipélago dos Açores é constituído por nove ilhas principais divididas em três grupos distintos: Grupo Ocidental (Corvo e Flores), Grupo Central (Faial, Graciosa, Pico, São Jorge e Terceira) e Grupo Oriental (Santa Maria e São Miguel)

O Grupo Oriental inclui também um grupo de rochedos e recifes oceânicos, situados a nordeste de Santa Maria, chamado ilhéus das Formigas, ou simplesmente Formigas, que em conjunto com o recife do Dollabarat, constitui a Reserva Natural do Ilhéu das Formigas, um dos locais mais importantes para conservação da biosfera marinha no nordeste do Atlântico.

O ponto mais alto do arquipélago situa-se na ilha do Pico - e daí o seu nome, a Montanha do Pico - com uma altitude de 2352 metros.

Vulcanismo

O arquipélago dos Açores foi formado por actividade vulcânica durante o final do Terciário. A primeira ilha a surgir acima da linha média da água do mar foi Santa Maria, há cerca de 8,1 milhões de anos (Ma), durante o Mioceno. Seguiram-se, por ordem cronológica, São Miguel (4,1 Ma), Terceira (3,52 Ma), Graciosa (2,5 Ma), Flores (2,16 Ma), Faial (0,7 Ma), São Jorge (0,55 Ma), Corvo (0,7 Ma) e, a mais jovem, o Pico (0,27 Ma).

Evolução de magmas

Magmas são fluidos naturais originados a partir da fusão de rocha (s) e que se solidificam a temperaturas de algumas centenas de graus centígrados. Magma não é uma solução e o estado de fusão (líquido + gás/gases) é decorrente da alta temperatura em que se encontra. Sua composição é predominantemente silicatada, mas pode conter gás/gases (aprisionado em forma de bolhas), ou mais raramente, ser composto de carbonatos, sulfetos, óxidos etc. O magma é formado quando são alcançadas as condições de temperatura e pressão adequadas para a fusão de rochas. Os magmas podem ser formados no manto e na crosta inferior, ou podem representar uma mistura de materiais fundidos em ambas as regiões.

Durante a ascensão do magma até a superfície ou em direção a porções mais rasas da crosta, uma série de processos – também conhecidos como variações secundárias – pode levar à modificação do magma formado.

Existem pelo menos três mecanismos de diferenciação magmática: cristalização fracionada, imiscibilidade de líquidos e fracionamento de líquidos. A cristalização fracionada decorre da cristalização progressiva de minerais diversos, a partir de um magma parental e com o decaimento de temperatura, de maneira a cristalizarem primeiro os minerais de mais alto ponto de fusão (os mais ferro-magnesianos), resultando em cristais e magma residual que têm, separadamente, composição diferente da do magma original. Com o avanço do processo, têm-se minerais mais félsicos sendo cristalizados. Estas fases minerais fracionadas podem se concentrar e formar rochas de diversas composições através de vários processos, como: (a) decantação de cristais mais pesados em camadas no fundo da câmara magmática (acumulações desses cristais são conhecidas como “cumulados”), (b) flotação de cristais mais leves em camadas mais para o topo, (c) filtragem do magma residual pressionado/bombeado para fora da câmara magmática com concentração de minerais em bandas devido ao fluxo hidráulico do magma com seus cristais em suspensão.

![]()

A imiscibilidade de líquidos envolve a separação de um magma originalmente homogêneo em duas frações líquidas coexistentes. Em fusões silicatadas, o grau de imiscibilidade é muito pequeno, mas em fusões de composição silicato-carbonato e silicato-sulfeto a imiscibilidade líquida é mais extensa.

Alguns magmas podem se tornar heterogéneos sem cristalização e sem dividir em frações imiscíveis, através do fracionamento de líquidos. Este fracionamento ocorre por difusão termal e gravitacional. Difusão termal significa que elementos ou moléculas, a temperaturas diferentes, migram de um lugar para outro. Certos constituintes, geralmente os pesados, migram para porções mais frias e outros, os mais leves, para porções mais quentes de um líquido magmático. Difusão gravitacional envolve a separação de elementos pesados ou leves, em um magma completamente líquido, por gravidade. Em termos simples quanto mais branca é o magma, mais evoluído está.

Contaminação ou assimilação

Durante a ascensão em direção à superfície, o magma pode incorporar material das rochas encaixantes. Existem dois mecanismos pelo qual o material contaminante pode ser incorporado ao magma: (a) fusão e mistura da fração fundida do material contaminante ao corpo principal de magma; (b) reação química e incorporação mecânica, não envolvendo fusão. Este segundo processo é o mais importante e frequente.

Mistura de magmas

Magmas de composições similares ou distintas podem ocorrer juntos e, portanto, há possibilidade de haver mistura entre eles, formando um produto híbrido de composição intermediária. A mistura de magmas ocorre fundamentalmente durante a residência em câmaras magmáticas, como conseqüência do aporte de novos pulsos de magmas primários, que variam a composição do magma ali acumulado. Importante ressaltar que diferenças de densidade e viscosidade tendem a inibir este processo.

Ribeira Quente

Ribeira Quente é uma freguesia do concelho da Povoação, com 9,88 km² de área, 767 habitantes (dados de 2011) e densidade de 77,6 hab/km².

A Freguesia da Ribeira Quente (Concelho da Povoação) na zona nordeste da costa sul é constituída por Andesitos e Andesitos Períodotíticos enquanto que na zona noroeste da costa sul é constituída por material Complexo Basáltico Nordeste. O material que abrange a maior parte da Freguesia é os Materiais Piroclásticos e Materiais de Projeção, enquanto que na zona centro encontra-se rochas eruptivas, Traquitos e Latitos.

Praia do Fogo (Ribeira Quente)

Inserida numa baía de grande beleza natural, com o verde das montanhas como cenário de fundo, a Praia do Fogo ou da Ribeira Quente possui um areal de pequenas dimensões mas muito acolhedor.

A EarthCache

Esta leva-te a um local com com magmas erodidos. Neste local baseia-te nas tuas observações para responder às seguintes perguntas:

1- 1- Dado que magmas mais evoluídos são mais claros e os menos evoluídos mais escuros, como é que avalias o grau de evolução das magmas que deram origem a estes depósitos?

2- 2- Qual á granulometria media dos sedimentos neste local?

3- 3- Qual é a mineralogia típca que encontras aqui? (Lembra-te que os minerais transparentes são normalmente da série continua de Bowen enquanto que os escuros são da série discontínua de Bowen).

4- 4- Baseado na resposta da pergunta anterior, de que série (continua ou descontínua) provêm os minerais presentes?

Enviem-me as respostas por mail para validar o “found”.

|

The Azores

Officially the Autonomous Region of the Azores (Região Autónoma dos Açores), is one of the two autonomous regions of Portugal, composed of nine volcanic islands situated in the North Atlantic Ocean about 1,360 km west of continental Portugal and approximately 880 km northwest of Madeira.

The nine islands that comprise the archipelago occupy a surface area of 2,346 km2 (906 sq mi), that includes both the main islands and many islets located in their vicinities. Each of the islands have their own distinct geomorphological characteristics that make them unique: Corvo (the smallest island) is a crater of a major Plinian eruption; Flores (its neighbor on the North American Plate) is a rugged island carved by many valleys and escarpments; Faial characterized for its shield volcano and caldera (Cabeço Gordo); Pico, is the highest point, at 2,351 meters (7,713 ft), in the Azores and continental Portugal; Graciosa is known for its active Furnas do Enxofre and mixture of volcanic cones and plains; São Jorge is a long slender island, formed from fissural eruptions over thousands of years; Terceira, almost circular, is the location of one of the largest craters in the region; São Miguel is the largest island, and is pitted with many large craters and fields of spatter cones; and Santa Maria, the oldest island, is heavily eroded, being one of the few places to encounter brown sandy beaches in the archipelago. They range in surface area from the largest, São Miguel, at 759 km2 to the smallest, Corvo, at approximately 17 km2.

These islands have naturally evolved into three recognizable groups located within the Azores Platform and they are:

Geostructural setting

From a geostructural perspective the Azores is located above an active triple junction between three of the world's large tectonic plates (the North American Plate, the Eurasian Plate and the African Plate),a condition that has translated into the existence of many faults and fractures in this region of the Atlantic. The westernmost islands of the archipelago (Corvo and Flores) are located in the North American Plate, while the remaining islands are located within the boundary that divides the Eurasian and African Plates.

Volcanism

The island's volcanism is associated with the rifting along the Azores Triple Junction; the spread of the crust along the existing faults and fractures has produced many of the active volcanic and seismic events, while supported by buoyant upwelling in the deeper mantle, some associate with an hotspot. Most of the volcanic activity has centered, primarily, along the Terceira Rift. From the beginning of the island's settlement, around the 15th century, there have been 28 registered volcanic eruptions (15 terrestrial and 13 submarine). The last significant volcanic eruption, the Capelinhos volcano (Vulcão dos Capelinhos), occurred off the coast of the island of Faial (in 1957); the most recent volcanic activity occurred in the seamounts and submarine volcanoes off the coast of Serreta and in the Pico-São Jorge Channel.

The islands of the archipelago were formed through volcanic and seismic activity during the Neogene Period; the first embryonic surfaces started to appear in the waters of Santa Maria during the Miocene epoch (from circa 8 million years ago). The sequence of the island formation has been generally characterized as: Santa Maria (8.12 Ma), São Miguel (4.1 Ma), Terceira (3.52 Ma), Graciosa (2.5 Ma), Flores (2.16 Ma), Faial (0.7 Ma), São Jorge (0.55 Ma), Corvo (0.7 Ma) and the youngest, Pico (0.27 Ma).

The evolution of magmas

As magmas moves, primarily upwards, two fairly obvious things that can happen to a magma to change it:

1- Assimilation of existing rocks

Magma moving upward, or sideways, within the Earth, will take in rock along the edges of magma chambers, even in huge pieces, and the aped material will be melted into the magma, changing its composition somewhat. If an intermediate composition magma moves upward into continental crust, which is a mixture of all types of rocks, assimilation of country rock will result in a diluting of iron and magnesium content (the aped material doesn't have as much iron and magnesium, usually). So, the magma may become felsic in composition after the assimilation.

2- Mixing of magma

Two magmas, perhaps of differing composition, can mix together if they come into contact, and the resulting magma is a kind of combination, most likely different from either of the original magmas.

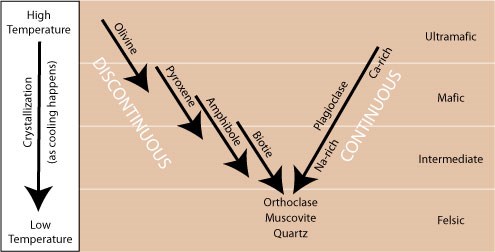

However, magma can evolve in less obvious ways. As magma crystalises certain crystals grow from it taking out the raw materials for their crystals from the magma. In the case of olivine, which starts crystallizing first, at high temperatures, iron and magnesium, along with silica, are taken out of the magma, depleting it of these substances. As other minerals grow, they will likewise remove certain chemical elements from the magma. So, the overall composition of the magma changes (i.e. the magma evolves), as crystallization happens – This is what is known as Bowen’s Reaction Series, named after Norman Bowen; famed experimental petrologist.

Norman Bowen did laboratory experiments to determine the order of crystallization of minerals growing in a magma as it cools, and made a chart showing the order. This is called Bowen's Reaction Series, and is important to understanding how magmas evolve. Why is it important? Because early formed igneous rock (less evolved) might contain one set of minerals, but a later forming igneous rock (more evolved), forming from the same magma, but changed, will have a different mineralogy. For such things as ore deposits like gold and silver, understanding how minerals crystallize helps you map out where you think deposits are located within mountain ranges.

First, observe the layout of the chart. High temperature is on top, so you can imagine that time progresses down the page; minerals crystallize in a sequence, from top to bottom (This chart is just an abstraction, used to explain the process). On the right, you see the compositions you've learned: ultramafic, mafic, intermediate, down to felsic. In the middle you have familiar silicate minerals. On the left side you see olivine, augite (pyroxene), hornblende (amphibole), and biotite. On the right side you see plagioclase, ranging in composition from all calcium, to 50:50 calcium and sodium, to all sodium toward the bottom (Sodium and calcium substitute for one another, in a proportion dependent on temperature). And under the left and right sides, you see orthoclase (potassium feldspar), muscovite, and then quartz at the bottom. The two sides have names: the left side is called the discontinuous reaction series and the right side is called the continuous reaction series:

Discontinuous Reaction Series - why discontinuous, as in start-stop? Because there are different minerals crystallizing in an order, first olivine, then pyroxene, then amphibole, then biotite, with a little bit of overlap in time for each transition.

Continuous Reaction Series - You can see why it is called continuous: there is only one mineral involved, plagioclase, and the only thing that happens as the temperature drops (going down the chart), is that sodium takes the place of calcium more and more.

And, finally, as you trace down from the two sides, you see orthoclase, then muscovite, and finally, emphasis on finally, quartz crystallizes. Now you might be seeing some things:

There is a range of temperature across which a given mineral will grow. Crystals of the mineral start to grow, they continue to form and grow as the temperature drops, but then they stop forming and growing, and other minerals grow instead.

Earlier formed minerals, such as olivine, will 'hang around' in the magma, as other minerals grow. The period of 'hanging around' is one wherein the rims of early formed crystals will react a bit with the magma, which is changing in chemistry; it is evolving over time. When you look at olivine and pyroxene crystals up close with a microscope, you can sometimes see reaction rims.

Not so for plagioclase. Instead of a start-stop affair, it just keeps growing, simply taking in more sodium at the expense of calcium as the temperature drops. A single plagioclase crystal will have a different composition on the inside (formed when the crystal was a 'baby'), and a different composition in the middle, and on the outside. Such zoned plagioclase crystals are common.

Late forming minerals, especially quartz, have to grow in the space remaining between the earlier formed mineral crystals. Usually, quartz is crammed in between the other minerals, because it is the last to form.

Now, and most importantly, take a look at the compositions along the right hand side of the chart:

Ultramafic igneous rocks form at high temperatures from minerals that begin to grow at those higher temperatures (olivine, Ca-rich plagioclase).

Mafic igneous (dark in colour; less evolved magmas)rocks also form at higher temperatures, as minerals such as pyroxene (augite), amphibole (hornblende) and Ca-Na plagioclase grow.

Intermediate igneous rocks (intermediate colour) form in a mid-level temperature range, and contain perhaps a little bit of pyroxene, a good bit of amphibole, biotite, and Na-rich plagioclase.

Felsic igneous rocks (lighter in colour), i.e. more evolved magmas, form at the lowest temperatures, from the suite of minerals toward the bottom of the chart.

So there you have it. Norman Bowen's chart helps you to make sense of magma crystallization.

Finally, we've been discussing what happens as the temperature drops and minerals grow. This same chart is useful to help thinking about what happens in the reverse process, when existing solid rock gets heated up, to the point when minerals start to melt. Which minerals are the first to melt? The last ones to crystallize, those on the bottom, such as quartz and muscovite and orthoclase. If heating doesn't take it all the way to total melting, these more siliceous minerals get melted off, and magma generated never gets any of the high iron and magnesium content of minerals like olivine, pyroxene, and amphibole. Recall partial melting? Now you might be getting the importance of this process to the generation of intermediate composition magmas from a mafic source rock.

Ribeira Quente Beach

Situated on the South side of S. Miguel Island west of the town of Povoação it is an arcuate beach approximately 650 linear metres located in the Volcanic Complex of Povoação.

The EarthCache

This one will take you to the beach where you have to observe the product of some weathered magmas. Here, based on your observations you will answer the following questions:

1- 1- Given that less evolved magmas are dark in nature and more evolved magmas are lighter in colour, how you grade the evolution of the magmas on this beach?

2- 2- What is the average grain size above the high water line at the GZ coordinates?

3- 3- What is the general mineralogical composition? (Transparent minerals are generally from the continuous Bowen series while the dark ones are normally from the discontinuous Bowen series).

4- 4- Is the observed mineralogy generally from the continuous or discontinuous Bowen series? Justify the answer.

Your correct answers by mail will validate one more find.

|