DGS: Gettin' Dirty at the Bend EarthCache

This cache has been locked, but it is available for viewing.

DGS: Gettin' Dirty at the Bend

-

Difficulty:

-

-

Terrain:

-

Size:  (not chosen)

(not chosen)

Please note Use of geocaching.com services is subject to the terms and conditions

in our disclaimer.

Horseshoe Bend

Cache placement has been approved by

Brian Carey

Deputy Superintendent

Glen Canyon National Recreation Area

Rainbow Bridge National Monument

928.608.6209 office

Safety First: Take plenty of water. Wear sunglasses, sunscreen, and a hat. Avoid hiking during the hottest part of the day. Tell a friend where you are hiking and when you will be home. There are no guard rails at the viewpoint. Watch your footing, and keep track of your children!

Leave No Trace: Pack garbage out. Don’t disturb any plants, rocks, or animals you come across. Dogs must stay on leashes no longer than six feet.

Trail Details: Distance: 1.5 miles(2.4 km) roundtrip. Walking time: 45 minutes. You will be walking up and down a sandy hill and across a gentle sandstone incline.

Crunchy Rocks

As you descend, the path is a little bumpier. It alternates between a whitish gravel, more sand, and some pretty solid, sloping rocks, the Navajo Sandstone. Notice how the rock itself has diagonal striped layers. These are the remnants of the layers of the ancient massive sand dunes before they were petrified into stone. The whitish stones tell us how the sandstone was petrified. This rock is calcite, or limestone, the same rock that drips itself into cave formations. Back 180 million years ago, this mineral mixed in with the rain and snow to cement the grains of sand together. The process took about 20 million years, but eventually all of the sand dunes were petrified by the calcite, retaining their beautiful sloping dune shapes. Today, as the grains of sand erode, chunks of the calcite also present themselves. As you get closer to the viewpoint, some of the rocks are covered with hard, sandy bumps. These are concretions of iron. Iron, being heavier than sand grains, was attracted to itself in ball shape while the sandstone was being petrified. Now that the sandstone is eroding away, the iron concretions are coming into view as well. When the little concretion balls break free from the rock, they are known as

"Mokie Marbles"

The Trail

Welcome to the Horseshoe Bend trailhead. Whether this is your first or hundredth visit to this awe-inspiring bend in the Colodaro River, you are guaranteed to see something new. The colors of the rocks change throughout the day, the shadows move in and out of the canyons, and as the river flows, it sparkles and shines in different shades of green and blue. As you make your way along the trail, use this guide to bring you closer to some of the details others may have missed along the way.

Recycled Sand

As you walk up the path, the trudge up the sandy hill might seem like a nuisance; but it is actually a walk through cycles of time. About 200 million years ago this sand was part of the largest system of sand dunes the North American continent may have ever seen. These “sand seas” are known as ergs. Our enormous erg was eventually hardened by water and minerals into Navajo Sandstone, an amazing uniform, smooth sandstone layer. It stretches from Arizona to Wyoming, and it can be over two thousand feet thick in some places. When you reach the edge of Horseshoe Bend you will be looking down 1000 feet ( 305 meters) of the sandstone to the river. After the Navajo Sandstone hardened, other layers of sandstone, mudstone, and different sedimentary layers piled on top of it. Then, after a couple of million years, patient water in the form of rain, ice, floods, and streams, worked to erode away the different layers. Today the Navajo Sandstone is once again exposed, and its sand is slowly wearing away. So now, what you are walking upon is sand from the Navajo Sandstone, which was from the giant Jurassic erg – recycled sand!

Where am I?

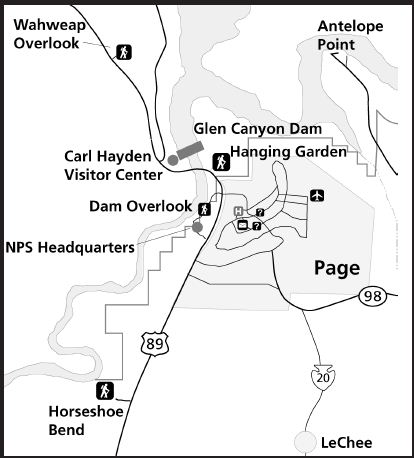

Are you at the top of the hill? Look around you. In front of you is the rest of the trail to Horseshoe Bend, and beyond that are the Paria Plateau and Vermillion Cliffs, managed by the Bureau of Land Management. To your right the river leads up to Lake Powell in Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. Behind you, the ever-growing city of Page. And to your left stretches the vast Navajo Nation. You are standing at the crossroads of these unique natural and cultural meeting places.

Horseshoe Bend

You’ve made it. Worth the walk, wasn’t it? The view of Horseshoe Bend from the rim of the canyon is extraordinary. (You’ll need a wide-angle lens to get the entire scene in your picture!) If you find the height a little daunting, try lying down on the ground and looking over the edge that way. It gives you a much better sense of security. Make sure you keep an eye on your animal companions as well; they can slip as easily as you. Below you, the Colorado River makes a wide sweep around a sandstone escarpment. Long ago, as the river meandered southward toward the sea, it always chose the steepest downward slope. This downward journey did not always occur in a straight line, and sometimes the river made wide circles and meanders. As the Colorado Plateau uplifted about 5 million years ago, the rivers that meandered across the ancient landscape were trapped in their beds. The rivers cut through the rock, deep and fast, seeking a new natural level. Here at Horseshoe Bend, the Colorado River did just that, and as the river cut down through the layers of sandstone, it created a 270° horseshoe-shaped bend in the canyon. Conceivably, at some time far in the future, the river could erode through the narrow neck of rock, creating a natural bridge and abandoning the circular channel around the rock. Maybe in a few million years, this will be the site of a brand new natural bridge formed the same way as nearby Rainbow Bridge National Monument.

Navajo Sandstone

frequently occurs as spectacular cliffs, cuestas, domes, and bluffs rising from the desert floor. It can be distinguished from adjacent Jurassic sandstones by its white to light pink color, meter-scale cross-bedding, and distinctive rounded weathering. The wide range of colors exhibited by the Navajo Sandstone reflect a long history of alteration by groundwater and other subsurface fluids over the last 190 million years. The different colors, except for white, are caused by the presence of varying mixtures and amounts of hematite, goethite, and limonite filling the pore space within the quartz sand comprising the Navajo Sandstone. The iron in these strata originally arrived via the erosion of iron-bearing silicate minerals. Initially, this iron accumulated as iron-oxide coatings, which formed slowly after the sand had been deposited. Later, after having been deeply buried, reducing fluids composed of water and hydrocarbons flowed through the thick red sand which once comprised the Navajo Sandstone. The dissolution of the iron coatings by the reducing fluids bleached large volumes of the Navajo Sandstone a brilliant white. Reducing fluids transported the iron in solution until they mixed with oxidizing groundwater. Where the oxidizing and reducing fluids mixed, the iron precipitated within the Navajo Sandstone. Depending on local variations within the permeability, porosity, fracturing, and other inherent rock properties of the sandstone, varying mixtures of hematite, goethite, and limonite precipitated within spaces between quartz grains. Variations in the type and proportions of precipitated iron oxides resulted in the different crimson, vermillion, orange, salmon, peach, pink, gold, and yellow colors of the Navajo Sandstone. The precipitation of iron oxides also formed laminea, corrugated layers, columns, and pipes of ironstone within the Navajo Sandstone. Being harder and more resistant to erosion than the surrounding sandstone, the ironstone weathered out as ledges, walls, fins, "flags", towers, and other minor features, which stick out and above the local landscape in unusual shapes.

Little Tiny Boats

Fishermen and recreational boaters frequent the 15 miles of Colorado River between Glen Canyon Dam and Lees Ferry. This is the stretch of calm water Major John Wesley Powell floated during his 1869 and 1871 explorations of the Colorado River before he started hitting rapids again downstream in Marble Canyon. The calmness of the water and greenery on the canyon walls inspired him to name Glen Canyon. This stretch of the river is a worldrenowned trout fishery. The clear, cold, slow-flowing water makes for a great trout habitat. These same conditions, plus the opportunity to see the last stretch of Glen Canyon unaffected by the Glen Canyon Dam attracts kayakers, rafters, and fishermen.

Logging Requirements - Answer following Questions

(Send answers via email. Do Not Post answers in log. Do not wait on me to respond to log your find!)

Make a tiny mound from Navajo Sandstone and pour water on top of the mound. Wait a few minutes. Now scoop the mound of sandstone from underneath. Spoiler Photo

1 Describe what happened to the sandstone!

2 Describe what happens if you gently blow on your newly created sandstone formation!

3 Describe the texture and strength of the formation compared to the original mound!

What did you learn from your reading

4 Why did the Colorado River make this 270 degree horseshoe shape?

5 What do you think horseshoe bend will look like 5 million years from now?

6 How many millions of years did it take sand dunes to become petrified by the calcite, retaining their beautiful sloping dune shapes?

7 The different colors, except for white, are caused by the presence of varying mixtures and amounts of what filling the pore space within the quartz sand comprising the Navajo Sandstone.

Where am I? - get reading from your GPS

8 What is the difference in elevation from the top of the hill to the horseshoe bend overlook?

Optional Logging Requirements

Post a photo

Additional Hints

(No hints available.)