Der Gletscherweg Innergschlöß führt von einem der schönsten Talschlüsse der Ostalpen in die Gletscherregion der Venedigergruppe empor. Entlang des Gletscherweges vermitteln 28 in Stein gemeißelte Haltepunkte, in Begleitung des Naturkundlichen Führers „Gletscherweg Innergschlöß“ (weitere Informationen here) , Wissenswertes über Schlatenkees und seine Gletschervorfelder, Gletschermessungen, Gletscherbäche, Salzbodensee, Auge Gottes, Tier- und Pflanzenwelt und ihre Anpassungen an das Hochgebirge u.v.a.m.

The educational nature trail itself is 4-5 hours round hike with cca 550 meters change in elevation. It is necessary take into account additional 2-3 hours and 200 meters change in elevation for way from Matreier Tauernhaus to Venedigerhaus and back , it is possible to use taxi, but we recommend to take at least one way by walk to see beauty of the Gschlöß valley (see gallery).

The nature trail has only few real information panels but it has 28 well marked stops, detail description of these stops can be found in information brochure “Gletscherweg Innergschlöß” published in cooperation by National Park Hohe Tauern and Oesterreichische Alpenverein (more information here). Due to severe weather conditions this brochure substitutes information panels, it is also possible buy it at Matreier Tauernhaus or Venedigerhaus (6-7 EUR, only German version).

Here is a description of the hike from document of the National Park Hohe Tauern:

One of the most beautiful hikes in the Venediger area leads into the heart of the national park. From the Matreier Tauernhaus, one can at first go by foot, by alpine taxi or by horse-drawn carriage on an alpine path to the alpine villages of Außer- and Innergschlöß (mountain chapel). From there, one must then proceed by foot to the valley-end and then steeply upwards over the shoulder of the slope to the famous “Auge Gottes” (2,240 m). The piece of trail that now follows, over the big moraine to the glacier Schliff and glacier-edge of the Schlatenkees, is especially impressive. The way back into the valley leads over the mountain flank of the Kesselkopf.

(Source: “Walking destinations” by Nationalpark Hohe Tauern here.)

Logerlaubnis

Um sich einzuloggen "Found it" für diesen Earthcache die folgenden Aufgaben zu beenden:

Erstens schicken Sie uns per E-Mail (über unser Profil) mit Antworten auf folgende Fragen:

1) Welche Type von Moräne ist an dem ersten Haltepunkt des Lehrpfades Gletscherweg Innergschlöß zu sehen?

2) Welche Type von Moräne ist an dem zehnten Haltepunkt der Naturlehrpfad Gletscherweg Innergschlöß zu sehen?

3) Was ist die Nummer vom Haltepunkt des Lehrpfades Gletscherweg Innergschlöß nah an den angegebenen Koordinaten (N 47 ° 06.995 E 012 ° 25.661)?

4) Was ist die Seehöhe des Photopoint bei N 47 ° 06.896 E 012 ° 24.830 (verwenden Sie Ihr GPS)?

(Für das Finden der Antworten ist es nicht nötig eine Informationbroschüre zu kaufen).

Zweitens (freiwillig aber gerngesehen) fotografieren Sie sich oder Ihr GPS bei die gewünschten Koordinaten (Photopoint bei N 47° 06.896 E 012° 24.830) mit Blick auf die Schlatenkees Mund zu Ihrem "Found es log" (siehe Muster). Die Photopoint liegt nahe der Haltepunkt Nummer 24 der Naturlehrpfad Gletscherweg Innergschlöß

(Um das Bild aufzunehmen braucht man den Wanderweg nicht zu verlassen.).

Bitte: Schicken Sie uns per Email die Antworten und gleich können Sie loggen. Falls nötig kontaktieren wir Sie. Die Antworten schreibein Sie nicht ins Log!

Log permission

In order to log „Found it“ for this earthcache finish the following tasks:

First send us email (via our profile) with answers to the following questions:

1) What type of moraine you can see at the first stop of the nature trail Gletscherweg Innergschlöß?

2) What type of moraine you can see at the tenth stop of the nature trail Gletscherweg Innergschlöß?

3) What is the number of the stop of the nature trail Gletscherweg Innergschlöß close to the given coordinates (N 47° 06.995 E 012° 25.661)?

4) What is the altitude of the Photopoint at N 47° 06.896 E 012° 24.830 (use your GPS)?

(For finding the answers it is not necessary to buy information brochure).

Second (optional but welcome) add a picture of you or your GPS at the required coordinates (Photopoint at N 47° 06.896 E 012° 24.830) together with view towards the Schlatenkees mouth to your „Found it“ log (see sample). The Photopoint is close to the stop number 24 of the nature trail Gletscherweg Innergschlöß.

(To taking picture it is not necessary to leave the path).

You can log directly after sending the email with answers, if there is any problem we will contact you. Do not to write answers in your log!

Das Schlatenkees – einer der imposantesten Gletscher im Hohe Tauern

Besonders faszinierende Landschaftselemente der Berge der Ostalpen sind ihre Gletscher. Sie prägen große Teile der Alpen durch den glazialen Formenschatz.

Das Schlatenkees im Talschluss des Gschlößtals ist mit 900 ha Fläche und 5 km Länge der größte Gletscher im Tiroler Teil der Venedigergruppe. Der Schlatenkees Gletscher ist sicherlich einer der imposantesten und schönsten Gletscher, die man in Österreich findet.

The Schlatenkees - one of the dominant glaciers of the Hohe Tauern

Glaciers are a particularly fascinating element of the eastern Alps' mountain landscape. In large areas of the Alps, glacial action has formed the distinctive features of the terrain.

The Schlatenkees is one of the dominant glaciers of the Hohe Tauern Mountains in Austria. It extends from the Großvenediger eastward and it is with a length of ca. 5 km and a surface ca. 900 ha one of the biggest glacier in Tirol.

Die Gletscherbildung

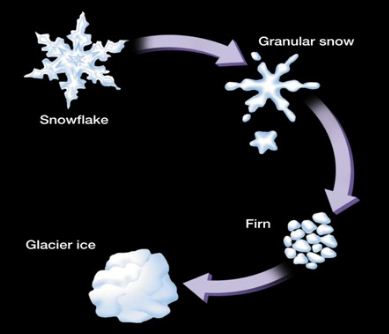

Gletscher sind Massen aus körnigem Firn und Eis, die aus Schneeansammlungen über Metamorphose hervorgegangen sind.

Gletscher entstehen vor allem in Polargebieten und Hochgebirgen, wo über viele Jahre hinweg mehr Schnee fällt als abschmilzt. Diese anhaltende jährliche Überproduktion ist die einzige unbedingte Voraussetzung für die Bildung von Gletschern.

Es sind keine besonders kalten Winter erforderlich, denn bei mildem Frost kann die Luft mehr Wasserdampf enthalten und daher stärkere Schneefälle als bei tieferen Temperaturen hervorbringen.

Das Fehlen ausreichender Energiemengen um den Schnee komplett wegzutauen ist von ebenso großer Bedeutung. Die Quantität des Schneeüberschusses ist weniger wichtig als die Qualität. Die Quantität an Schnee entscheidet nur über die Geschwindigkeit, mit der sich der Gletscher entwickelt.

Die Metamorphose des Schnees zu Gletschereis vollzieht sich in mehreren Stadien. Frisch gefallener Schnee (névé) hat eine spezifische Dichte von 50-300 Kilogram pro Kubikmeter. Als erstes schmelzen die Spitzen der sternförmigen Kristalle ab, dadurch wird der Schnee körnig. Hierbei wird die Schneemasse dichter und gleichzeitig fester. Der Druck des sich auflagernden Neuschnees trägt zur Verwandlung bei.

Wenn dieser Vorgang nun mehrere Jahre angehalten hat, verfestigt sich dieser körnige Schnee zu Firn (mittlere Dichte 500–700 Kilogram pro Kubikmeter). Durch den Druck der darüber liegenden jüngeren Schneemassen kristallisieren sich die Firnkörner zu einem festen Gefüge von Gletschereis (mittlere Dichte 800 – 900 Kilogram pro Kubikmeter, die Dichte von reinem Eis ist 917 Kilogram pro Kubikmeter bei 0° C). Die mittlere Dichte wird beim Gletschereis unter anderem durch den Anteil der eingeschlossenen Luftbläschen beeinflusst.

Wenn sich Eismassen von genügender Mächtigkeit gebildet haben beginnen sich diese zu bewegen. Der Impuls zur Bewegung ist hier durch die Graviation und die Eigendynamik, aufgrund der Masse des Eises, gegeben. Bei Gletscherbewegungen werden zwei Arten unterschieden, wobei oft eine Kombination beider Prozesse zur Mobilität eines Gletschers beitragen.

Basales Gleiten: Aufgrund des Eigengewichtes (hoher Druck erzeugt Wärme) und ggf. durch geothermische Prozesse, kann eine dünne Eisschicht an der Sohle eines Gletschers schmelzen und es bildet sich ein Schmelzwasserfilm. Da in Verbindung mit Wasser die Reibung am Gesteinsuntergrund sinkt können sich Eismassen im Vergleich zum plastischen Fließen durch basales Gleiten schnell fortbewegen und entwickeln dadurch eine weitaus größere Erosionskraft.

Plastisches Fließen: Durch den Druck der Eismasse eines Gletschers verformt sich diese und breitet sich im Untergrund aus. Die Aufsummierung der Einzelbewegungen der von Kontraktion beeinflussten Eiskristalle (hauptsächlich aufgrund der Schwerkraft hangabwärts gerichtet) ergibt die Gesamtbewegung des Gletschers in der plastischen Zone. Dieser Vorgang wird plastisches Fließen genannt. Aufgrund er Starrheit der oberen Eisschichten bilden sich beim Überqueren von Erhöhungen im Untergrund Bruchspalten im Gletscher aus. Plastisch fließende Gletscher erodieren durch das Herausbrechen von angefrorenem Gesteinsmaterial.

The Glacier Formation

A glacier is basically an accumulation of snow that lasts for more than a year. In the first year, this pile of snow is called a névé. Once the snow stays around for more than one winter, it's called a firn. Each year's accumulation is packed down by the next year's, until the pressure of its weight causes the snow to go through a series of mechanical changes that eventuate in glacial ice.

New snow is not very dense (ca. 50-300 kg per cubic meter), basically consisting of the ice lattice of interlocked snowflakes with plenty of air and maybe water vapor or even liquid water. As it's slowly compacted down and as the snow experiences both melting and sublimation, the original snowflakes lose much of their spikiness. They become more like rounded ice crystals. This can pack down more compactly and attain greater density (ca. 500 kg per cubic meter). This is called "névé," and it normally forms each year from any snow that falls and persists throughout the winter.

If the névé survives the entire ablation season, packing down and becoming blunter all the while, it becomes "firn." Each year's firn is packed down more and more tightly by the layers of firn forming above it, until most of the air is pressed out of it. At this point, with densities getting above 850 kg per cubic meter, the firn becomes true glacier ice. The ice continues to become denser through time as long as it exists in the glacier. Only rarely in mountain glaciers does the density exceed 900 kg per cubic metre, but at great depths in ice sheets the density may approach that of pure ice (917 kg per cubic metre at 0° C and atmospheric pressure).

(Source: CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY here.)

Eventually, the glacier becomes so heavy that it starts to move. There are two forms of glacial movement, and most glacial movement is a mixture of both.

Spreading occurs when the glacier's own weight becomes too much for it to support itself. The glacier will gradually expand and "spread out". Ice behaves like an easily breaking solid until its thickness exceeds about 50 meters. The pressure on ice deeper than that depth causes plastic flow.

Basal slip occurs when the glacier rests on a slope. Pressure causes a small amount of ice at the bottom of the glacier to melt, creating a thin layer of water. This reduces friction enough that the glacier can slide down the slope. Loose soil underneath a glacier can also cause basal slip. When a glacier moves, it isn't like a solid block of ice tumbling down a hill. A glacier is a river of ice, it flows. That's because the highly compressed layers of ice are plastic under great pressure.

Moränen

Fliessende Eismassen nehmen auf ihrem Weg verschiedenstes Gesteinsmaterial auf, transportieren es und lagern es um, um dann – wenn sie ihre Geschwindigkeit reduzieren bzw. ihre maximale Transportkapazität überschritten haben - wieder abzulagern. Solche Ablagerungen werden Moränen genannt. Es gibt verschiedene Moränentypen. Sie bestehen vornehmlich aus Lehm und gröberem Geschiebe, wie zum Beispiel vom Gletschereis transportierte und durch Entlanggleiten des Eises auf dem felsigen Untergrund mechanisch beanspruchte Gesteinsbrocken unterschiedlicher Grösse. Grosse Gesteinsblöcke können mehrere Tonnen schwer sein und werden Erratiker genannt.

Für Moränen charakteristisch ist, dass das sedimetierte Material ungeschichtet, unsortiert, und meist auch ungerundet oder kantengerundet ist.

Grundmoräne

Grundmoränen sind Ablagerungen subglazialen Ursprungs, also Gesteinsmaterial, welches unter dem Gletscher deponiert wurde. Die Ablagerung erfolgt, wenn die Eisbewegung zum Stillstand kommt und der Gletscher abtaut. Bestandteile der Grundmoräne sind Korngrößen aller Klassen, die gemischt, d.h. weitgehend unsortiert und ungeschichtet vorkommen.

Seitenmoräne oder Ufermoräne

Die Seitenmoränen entstehen dadurch, dass Material, welches der Gletscher an der Unterseite von dem Untergrund aufnimmt oder das durch Bergstürze auf ihn fällt, an den Seiten des Gletschers abgelagert wird.

Mittelmoräne

Mittelmoränen entstehen an der Stelle, wo sich zwei Gletscher vereinen. Es sind immer die Seitenmoränen, dich sich dann zu einer einzigen Mittelmoräne zusammenschließen.

Endmoräne oder Stirnmoräne

Diese Sonderform einer Moräne bildet sich bevorzugt an der Gletscherstirn. Die Endmoräne schließt sich bogenförmig an die Grundmoräne an und zeichnet den weitesten Vorstoß des Eises nach. Sie markiert eine über längere Zeit stationäre Randlage des Gletschers, so dass sich mächtige Wälle aus mitgeführtem Material anhäufen konnten. Endmoränen erreichen Höhen bis zu einhundert Metern und können sich über einige hundert Kilometer erstrecken. Sie bilden sich gemäß der Form der Gletscherzungen bogenförmig um diese herum. Man unterscheidet zwei Typen von Endmoränen: die Satzendmoräne und die Stauchendmoräne.

Satzendmoräne

Die Satzendmoräne entsteht durch sukzessive Moränenmaterialanreicherung im Eisrandbereich bei stationärer oder zurückschmelzender Eisrandlage. Es handelt sich also um Aufschüttungsmoränen, in denen Schmelzwässer die feineren Partikel ausgewaschen haben. Es bleiben Blockpackungen aus sehr groben Komponenten zurück, die oft zu Bruchsteinen, Schotter oder Splitt verarbeitet wurden.

Stauchmoräne

Stauchendmoränen entstehen besonders in der Vorrückphase eines Gletschers. Das vorrückende Eis staucht oder schiebt sowohl bereits abgelagerte ältere Moränen als auch Material des präglazialen Untergrundes auf.

Obermoräne

Sonderform der Moräne, die sich auf der Eisoberfläche des Gletschers befindet und dort mit der Eisbewegung transportiert wird. Obermoränen können durch herabfallenden Schutt entstehen, der durch den Prozess der Frostverwitterung gelockert wurde, oder von aus Hangrutschungen oder Bergstürzen stammendem Material gebildet werden.

Vereinzelt bedecken Obermoränen die gesamte Oberfläche und machen die Eismassen nur am Gletschertor, Brüchen oder Spalten sichtbar. Das von ihnen transportierte Material wird im Gegensatz zu anderen Moränenarten kaum glazial bearbeitet und bleibt daher meist kantiger, grober Schutt.

Glacial Moraines

Moraine is material transported by a glacier and then deposited. Deposition of material carried by the glacier occurs either as partial deposition as a result of a reduction in the velocity of the glacier or complete deposition as the glacier retreats and melts. There are eight types of moraine, six of which form recognisable landforms, and two of which exist only whilst the glacier exists. The types of moraine that form landforms are Ground, Lateral, Medial, Push, Recessional and Terminal. The two types only associated with glacial ice are Supraglacial and Englacial moraine.

Ground Moraine

Ground moraine is till deposited over the valley floor. It has no obvious features and is to be found where the glacier ice meets the rock underneath the glacier. It may be washed out from under the glacier by meltwater streams, or left in situ when the glacier melts and retreats.

Lateral Moraine

Lateral moraine forms along the edges of the glacier. Material from the valley walls is broken up by frost shattering and falls onto the ice surface. It is then carried along the sides of the glacier. When the ice melts it forms a ridge of material along the valley side.

Medial Moraine

Medial moraine is formed from two lateral moraines. When two glaciers merge, the two edges that meet form the centre line of the new glacier. In consequence two lateral moraines find themselves in the middle of the glacier forming a line of material on the glacier surface. The existence of a medial moraine is evidence that the glacier has more than one source. When the ice melts it forms a ridge of material along the valley centre.

Push Moraine

Push moraines are only formed by glaciers that have retreated and then advance again. The existence of a push moraine is usually evidence of the climate becoming cooler after a relatively warm period. Material that had already been deposited is shoved up into a pile as the ice advances, and because most moraine material was deposited by falling down not pushing up, there are characteristic differences in the orientation of rocks within a push moraine. A key feature enabling a push moraine to be identified is individual rocks that have been pushed upwards from their original horizontal positions.

Recessional End Moraine

End moraines are ridges of unconsolidated debris deposited at the snout or end of the glacier. There are two types of end moraines; terminal and recessional.

Recessional moraines form at the end of the glacier so they are found across the valley, not along it. They form where a retreating glacier remained stationary for sufficient time to produce a mound of material. The process of formation is the same as for a terminal moraine, but they occur where the retreating ice paused rather than at the furthest extent of the ice.

Terminal End Moraine

The terminal moraine forms at the snout of the glacier. It marks the furthest extent of the ice, and forms across the valley floor. It resembles a large mound of debris, and is usually the feature that marks the end of unsorted deposits and the start of fluvially sorted material.

Supraglacial Moraine

Supraglacial moraine is material on the surface of the glacier, including lateral and medial moraine, loose rock debris and dust settling out from the atmosphere.

Englacial Moraine

Englacial moraine is any material trapped within the ice. It includes material that has fallen down crevasses and the rocks being scraped along the valley floor.

(Source: ”The Geography Site for resources, homework, fun and virtual lessons for students and teachers”).

Gletcher Erosion

Eis alleine hat aufgrund seiner plastischen Verformbarkeit keine erosive Wirkung. Doch Gletscher hinterlassen dennoch deutliche kleinere Erosionsspuren wie Gletscherschrammen und große Erosionsspuren wie charakteristische Täler. Die Gletschererosion wird im Wesentlichen durch Detersion und Detraktion verursacht. Bei der Detersion wird die Erosion durch Steine verursacht, die an der Unterseite des Gletschers festgefroren sind. Die Steine hinterlassen auf dem darunterliegenden Gestein charakteristische Schrammen, die parallel zur Fließrichtung des Eises liegen. Die Spuren nennt man Gletscherschrammen und sie sind ein guter Anzeiger für ehemalige Vergletscherung. Bei der Detersion entsteht feiner Gesteinsstaub, welcher durch Schmelzwasser aus dem Gletscher transportiert wird und als Gletschermilch bekannt ist.

Detersion oder Gletscherschliff

Schleifwirkung (Detersion) der im und am Eis von Gletschern oder Eisschilden ein- und angefrorenen Fein- und Grobkomponenten der Untermoräne, die auf die Gletschersohle, die Wände des Trogtales oder den festen Untergrund des Inlandeises ausgeübt wird. Durch diese Form der glazialen Erosion wird die Felsoberfläche geglättet und poliert, die mitgeführten Geschiebe kritzen den Untergrund, was Striemen und Schrammen am Fels und am Geschiebe hinterlässt. Aus dem Verlauf der Gletscherschrammen im Fels kann die Fliessrichtung des Eises rekonstruiert werden.

Detraktion

Detraktion ist eine weitere Art der Erosion durch den Gletscher. Wasser unter dem Gletscherbett fliesst in Spalten und Rissen im Gesteinsuntergrund. Gefriert das Wasser wieder, entsteht eine Art Eismantel um das Gestein und es wird an der Gletscherunterseite angefroren. Durch die Bewegung des Gletscher wird das Gesteinsmaterial aus dem Untergrund herausgelöst. Nachgewiesen werden kann dieser Vorgang, indem herausgebrochene Blöcke in die Ausbruchstelle wieder eingepasst werden.

Glacial Erosion

Glacial erosion is a huge cause of change in the land and is one of the main forces of nature. The glaciers are able to erode the land because they pick up and carry debris that moves across the land along with the ice. The two main ways that glaciers erode the underlying rock are abrasion and plucking.

Abrasion (scouring)

Abrasion is the mechanical scraping of a rock surface by friction between rocks and moving particles during their transport by glacier. This is where the bedrock underlying the glacier is eroded by debris embedded in the base and sides of the glacier.

As the glacier moves over the bedrock, this material scrapes away at the rock like sandpaper wearing it away. As it does so it leaves behind scratches and grooves in the rock, known as striations. Where these grooves are discontinuous but regular in occurrence they are known as chatter marks. As the bedrock is eroded by abrasion, further material may become entrained in the ice increasing the amount of abrasion that is able to take place. Where fine material is embedded in the base of the glacier it will act to polish and smooth the bedrock below. Indeed as abrasion takes place, rock material is ground down to produce a very fine rock flour.

Abrasion also produces fine clay-sized sediment that is often transported away from the glacier by melt water. As a result of this process, glacial meltwater can have a light, cloudy appearance, and is called glacial milk.

Plucking (Quarrying)

Plucking (also known as quarrying) is a mechanical removal of pieces of rock from bedrock that is in contact with glacier ice. The process of plucking results in the removal of much larger fragments of bedrock than that undertaken by abrasion. Plucking occurs where ice is at pressure melting point. As the meltwater produced refreezes it entrains material in the base of the glacier. As the glacier continues to advance, the newly entrained material is broken out of the bedrock. This material is then able to be used in the process of abrasion.