ALGAR dos caneiros

UNDERGROUND LANDSCAPES

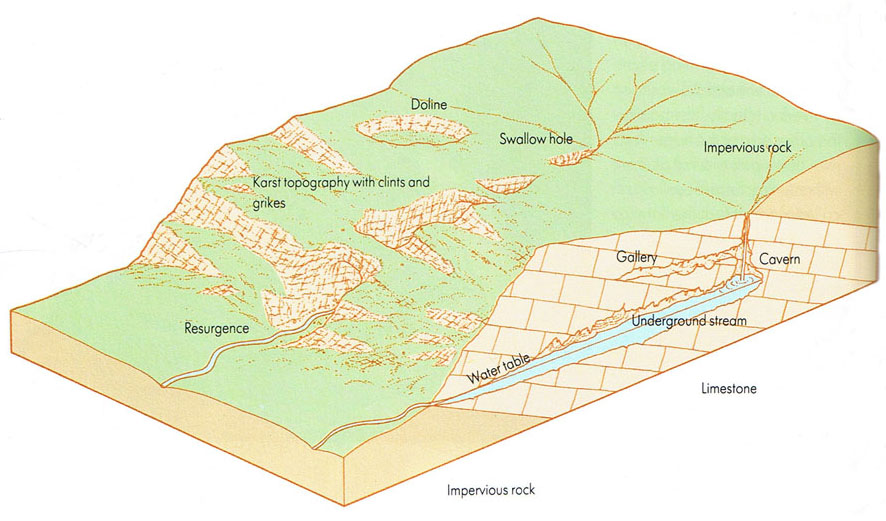

The rain falling on the landscape mostly perco-lates into the ground. It gathers in the saturation zone, where all the pores and crevices of the rock and soil are filled with water. The top of this zone is the water table - an important concept in engineering and drilling wells. Where the water table reaches the surface, as on a slope, the water seeps out in the form of a spring.

In a limestone terrain the situation can be more complex, and more spectacular. Limestone is made of calcite which dissolves away in the carbonic acid of the rain water. On the surface this solution takes place most quickly along the joints and fault planes, opening up crevices and separating the limestone mass into clints. This takes place underground too.

Most erosion follows the bedding planes of the limestone and the joints that tend to cut the bedding plane at right angles. It also takes place along the water table, where the surface of the water may form a stream and flow more or less horizontally. As a result a limestone terrain be-comes dissolved into a series of interlocking caverns. From time to time the water table may drop. A stream in a tunnel will then erode deeply into its bed and give a tunnel that is keyhole-shaped in cross-section. If the water table drops suddenly (in geological terms) the stream will begin to erode a new tunnel at the new level and leave the old one as a dry gallery. As the caverns expand, their roofs collapse, filling their floors and opening new spaces above. The collapse may cause the surface to cave in, leaving long gorges along the course of underground rivers, or broad depressions called dolines.

Vertical caves carved out by falling water are called potholes (not to be confused with the potholes that are carved out by swirling stones in a youthful river bed) or sink holes. Surface streams flowing off an area of impermeable rock may suddenly disappear down one of these when it meets limestone.

Some calcite is washed away to sea, but much of it is redeposited in the same area. Groundwater seeping through and hanging as a drop on the cavern roof may deposit its calcite there. Not because the water evaporates away - the humidity of a typical cavern would preclude this - but because the carbon dioxide is lost from the water and it ceases to be acidic enough to hold the calcite. Accumulati on of these calcite deposits builds up stalactites. When a drop hits the cave floor, the calcite is knocked out of it and an accumulation here forms a stalagmite. Different shapes of stalactite and stalagmite develop, each with a descriptive name. Water drawn along a stalagmite or a stalactite by capillary action, for example, will deposit its calcite seemingly at random and produce a twisted stalactite called a helictite.

on of these calcite deposits builds up stalactites. When a drop hits the cave floor, the calcite is knocked out of it and an accumulation here forms a stalagmite. Different shapes of stalactite and stalagmite develop, each with a descriptive name. Water drawn along a stalagmite or a stalactite by capillary action, for example, will deposit its calcite seemingly at random and produce a twisted stalactite called a helictite.

Calcite is deposited by agitation in the underground stream as well. As an underground stream flows over an irregularity it deposits calcite, which causes a bigger irregularity which deposits more calcite, and so on. The result is a sequence of steps and terraces in the stream bed looking just like a hillside of terraced paddy fields - structures called gours.

When the underground stream finally reaches the surface, it may form a petrifying spring. Here the water can evaporate and deposit its calcite on anything handy. Mosses are sometimes encrusted, as are trinkets left by sightseers.

Calcite is an important mineral in cementing unconsolidated sediment to form a solid rock. A visit to a petrifying spring where the speed of calcite deposition can actually be seen is a memorable demonstration of this.

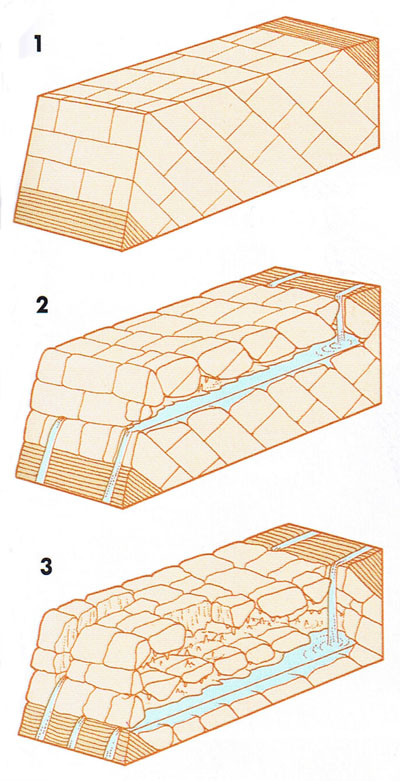

Groundwater sinks into holes and cracks dissolved into limestone:

1. At the water table it will flow horizontally, dissolving out a tunnel. Around it other openings will be dissolved along natural bedding planes and cracks in the rock

2. If the water table is lowered, the process is repeated at the lower level, leaving the original tunnel as a dry gallery

3. The ceiling may fall, opening up huge caverns.

(The Practical Geologist)

The Cache:

This cache takes you to a natural pit. This natural pit is denominated in the Portuguese terminology as Algar. This Algar communicates with the sea through a cave, that can be visited by small boats during the low tide. These cache pictures' were taken inside this cave.

To claim the cache, you have to:

-

What is the diameter of the Algar?

Now a little bit of research:

-

What is the famous formula of the dissolution of limestone?

-

What is terra rossa?

-

Optional: take a picture of you with MrGPS, where we can also see the Leixão da Gaivota.

Mail me the answers, and after permission, make your log.

A Cache:

Esta cache leva-o a um Algar situado perto do Farol do Ferragudo. Este Algar comunica com o mar através de um gruta, que pode ser visitada em barcos pequenos na maré vazia. As fotografias publicadas nesta página são tiradas no seu interior.

Para reclamar a cache, deve responder às seguintes questões:

-

Qual o diâmetro do Algar?

Para responder às próximas questões, à que fazer uma pequena pesquisa:

-

Qual a famosa fórmula de dissolução do calcário?

-

"Terra Rossa", o que é?

-

Opcional: tire uma fotografia sua com o MrGPS, onde seja possível visualizar também o Leixão da Gaivota.

Envia-me as respostas por mail, e após autorização faça o seu log.