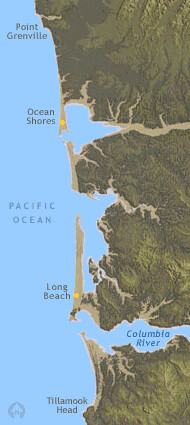

Along Washington's southwest coast, wide sand beaches stretch from the mouth of the Columbia River to Point Grenville. Along Washington's southwest coast, wide sand beaches stretch from the mouth of the Columbia River to Point Grenville.

Columbia River sand built beaches and barriers

For the past four to five thousand years, the Columbia River has carried sand to the coast. Currents, waves and wind have swept sand north and south -- from the Columbia River mouth to build up dunes and beaches. Millions of cubic yards of Columbia River sand are stored in these linear dunes and beaches, also called barriers. The Columbia River supplies sand to 100 miles of beaches, from Oregon's Tillamook Head to Washington's Point Grenville. As sand moves north up Washington's coast, the amount available to nourish beaches decreases. At Point Grenville, the trailing end of Columbia River sand is deposited. North of Point Grenville, the contribution of Columbia River sand to beaches is small.

Sand for miles

The Long Beach peninsula, a huge spit, was formed by sediments delivered to sea by the Columbia River. Waves and currents slowly reworked the sediments to build the 19 mile long peninsula which is only about a mile wide. Broad sand beaches front an upland sand plain, laced with parallel dune ridges, bogs, lakes, and woodlands.

|

HOW BEACHES ARE BUILT

Littoral Drift

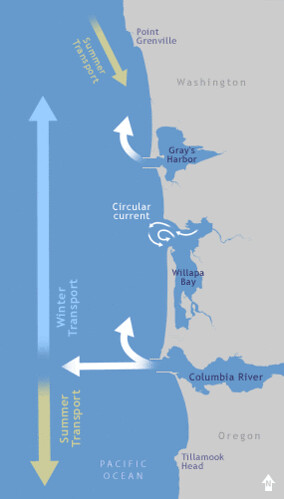

Waves come ashore diagonally, as their backwash flows perpendicular to the beach. Sediment particles travel in a zigzag path as they are moved along the beach. This motion creates a current that runs parallel to the beach. Storms can generate high waves that approach the shore at a larger angle, causing a faster current.

How sand is carried along Washington's southwest coast How sand is carried along Washington's southwest coast

Summer: During the summer, winds come from the northwest; sand moves south.

Winter: During the winter, winds come from the southwest; sand moves north. Because winter winds blow harder, the dominant drift direction is north.

For several thousand years, floods washed sand to the mouth of the Columbia River, where it collected in shoals. Longshore currents shuttle sand from these shoals, carry it along shore, and deliver it to beaches. Within the last century, the movement of sand from the Columbia River has been altered by dams, jetties, and other development.

HOW THE COAST WORKS

Erosion along Washington's southwest coast is affected by: jetties, dams, sediment supply, geologic history, wave action, and weather.

|

Jetties caused beaches to grow and possibly erode

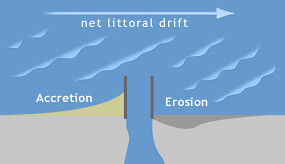

Jetties have influenced accretion and possibly erosion patterns on the beaches over distances of 12 miles (20 kilometers) or more.

|

|

|

Erosion and accretion near jetties

Where there is net littoral drift, jetties can block the flow of sand, causing erosion and accretion.

|

- In the early 1900s, jetties were built at the entrances to the Columbia River and Grays Harbor. These jetties were designed to scour out sandbars and keep navigation channels open. Beaches, inlet entrances, and the nearby sea floor are still changing as a result of jetty construction over a century ago.

- River deltas scoured

The jetties narrowed inlets and increased tidal currents. These currents flushed sand out of tidal deltas.

- Beach growth and erosion

Over decades, sand from the scoured deltas accumulated, causing beaches near the jetties to grow. Campgrounds and condominiums were built on this newly accreted land. The delta sand is now gone and beaches near the jetties are experiencing erosion.

|

|

Erosion damage to park beach access road at Fort Canby, following winter storms, 1997. |

Dams on the Columbia River have reduced the sand supply

Dams on the Columbia River have reduced the sand supply to coastal beaches by two thirds.

- Before dams were constructed, sand moved freely

Before dams were built on the Columbia River, floods carried sand to the delta, where it gathered in shoals. Longshore currents picked up the sand from the shoals, moved it along shore, and deposited it on beaches. The Columbia River carried about 12 million cubic yards of sediment to the coast per year.

- Dams have restricted the flow of sand by two-thirds

Beginning in the 1930's, dams were constructed over most of the U.S. part of the Columbia River. Dams restricted sediment supply from 90 percent of the watershed, a quarter of a million square miles. As a result, the Columbia River delta has been starved of critical beach building sand.

- Delayed effects

Peacock Spit, a huge shoal north of the mouth of the Columbia, supplied sand to coastal beaches for decades. Peacock Spit is now gone. The spit may have been scoured away by jetty-influenced currents. With sand in short supply, Washington's southwest coast may be entering a long-term period of erosion.

El Niño impacts the shoreline

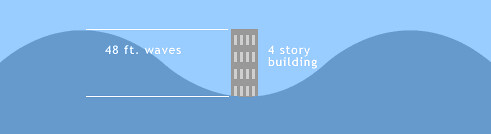

El Niño, a recurring atmospheric phenomenon, can bring higher sea levels, intense storms, and extreme high waves from the southwest.

The El Niño winter of 1997/98, the strongest El Niño of the century, brought frequent storms and high waves. On January 17th, 1997, the Grays Harbor wave gauge reported a wave as tall as a four story building, 48 foot high (14.52 meters). A storm system or squall line surge produced this extreme wave. This storm caused massive overwash and erosion at Ft. Canby State Park.

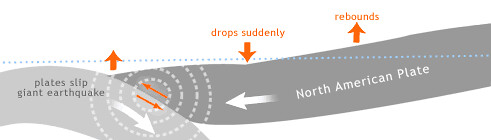

Earthquakes hit Washington's coast

Large earthquakes in the past caused the coast to sink 3 to 6 feet suddenly (1 to 2 meters).

|