Carta de James

O’Hara

Lisboa, 12 de

Novembro, 1755

"Querida

irmã,

Sento-me para te relatar a catástrofe horrorosa que se abateu

sobre a até então florescente cidade de Lisboa, agora uma

cena de horror e desolação.

No primeiro dia deste mês, às nove e meia da manhã,

um súbito terramoto fez tremer as suas fundações, e

deixou-a em ruínas. Nesta fatal hora, as igrejas estavam

cheias; e como o seu desmoronamento foi imediato, não tendo

havido tempo para fugir, aqueles que lá estavam foram

esmagados.

É impossível descrever o ar aterrorizado dos habitantes,

tentando fugir de qualquer modo para evitar a destruição.

Inúmeros acorreram à margem do rio com esperança de

salvar as duas vidas por meio de embarcações. O cais da

alfândega pensava-se um lugar seguro; mas infelizmente foi

logo inundado, e todos aqueles que por ali fugiram, só

escaparam de uma cidade em desmoronamento para ali encontrar uma

morte na água. Pais e mães à procura dos seus

filhos, e crianças procurando os seus

pais."

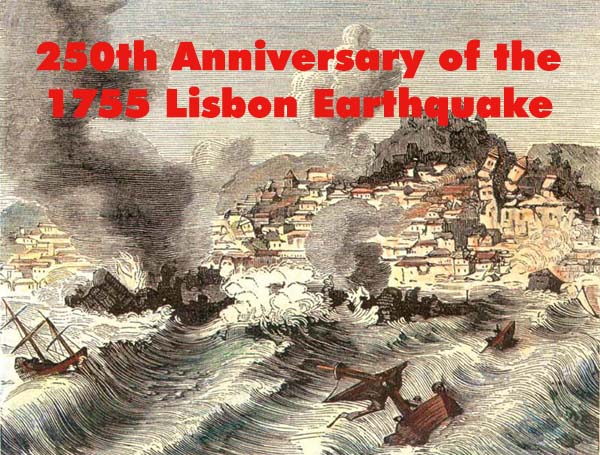

O Terramoto de 1755, como

ficou conhecido, aconteceu no dia 1 de Novembro de 1755 às

9h20m da manhã, resultando na quase total destruição

da cidade de Lisboa e de grande parte do litoral do Algarve. O

sismo foi seguido de um tsunami que se crê terá atingido

a altura de 20 metros e múltiplos incêndios, tendo feito

mais de 100 mil vítimas mortais. Foi um dos mais

mortíferos terramotos da história.

O terramoto teve um enorme impacto na sociedade

do Século XVIII, em especial na estrutura política em

Portugal e tornou-se o primeiro estudo cientifico do efeito de um

terramoto numa área alargada. Os geólogos modernos

estimam que o sismo de 1755 atingiu 9 graus na escala

Richter.

O terramoto teve um enorme impacto na sociedade

do Século XVIII, em especial na estrutura política em

Portugal e tornou-se o primeiro estudo cientifico do efeito de um

terramoto numa área alargada. Os geólogos modernos

estimam que o sismo de 1755 atingiu 9 graus na escala

Richter.

O terramoto fez-se sentir

na manhã de 1 de Novembro, no feriado católico do dia de

Todos-os-Santos. Relatos contemporâneos afirmam que o

terramoto durou, consoante o local, entre seis minutos e 2 horas e

meia, causando fissuras gigantescas de cinco metros que cortaram o

centro da cidade de Lisboa. Com os vários desmoronamentos os

sobreviventes procuraram refúgio na zona portuária e

assistiram ao abaixamento das águas, revelando o fundo do mar,

cheio de destroços de navios e cargas perdidas. Dezenas de

minutos depois um enorme tsunami de 20 metros fez submergir o porto

e o centro da cidade. Nas áreas que não foram afectadas

pelo tsunami, o fogo logo se alastrou, e os incêndios duraram

pelo menos 5 dias.

Lisboa não foi a

única cidade portuguesa afectada pela catástrofe. Todo o

sul de Portugal, nomeadamente o Algarve, foi atingido e a

destruição foi generalizada. As ondas de choque do

terramoto foram sentidas por toda a Europa e norte da África.

Os tsunamis originados por este terramoto varreram desde a

África do norte até ao norte da Europa, nomeadamente

até à Finlândia e através do Atlântico,

afectando locais como Martinica e Barbados.

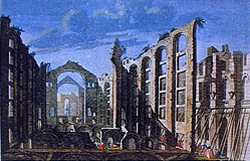

De uma população de 275 mil habitantes

em Lisboa, 90 mil foram mortos. Outros 10 mil foram vitimados em

Marrocos. Cerca de 85% das construções de Lisboa foram

destruídas, incluindo palácios famosos e bibliotecas,

igrejas, hospitais e todas as estruturas. Várias das

construções que sofreram pouco danos pelo terramoto foram

destruídas pelo fogo que se seguiu ao abalo

sísmico.

De uma população de 275 mil habitantes

em Lisboa, 90 mil foram mortos. Outros 10 mil foram vitimados em

Marrocos. Cerca de 85% das construções de Lisboa foram

destruídas, incluindo palácios famosos e bibliotecas,

igrejas, hospitais e todas as estruturas. Várias das

construções que sofreram pouco danos pelo terramoto foram

destruídas pelo fogo que se seguiu ao abalo

sísmico.

O Marquês do Pombal,

primeiro-ministro de D. José, sobreviveu ao terramoto. Com o

pragmatismo que caracterizou a sua governação, iniciou

imediatamente a reconstrução de Lisboa. A sua rápida

resolução levou a organizar equipas de bombeiros para

combater os incêndios e recolher os milhares de cadáveres

para evitar epidemias. O ministro e o rei, contrataram arquitectos

e engenheiros, e em menos de um ano depois do terramoto, já

não se encontravam ruínas em Lisboa e os trabalhos de

reconstrução iam adiantados. O rei desejava uma cidade

nova e ordenada a construção de grandes praças e

avenidas largas e rectilíneas, que marcaram a planta da nova

cidade. Na altura alguém perguntou ao Marquês de Pombal

para que serviam ruas tão largas, ao que este respondeu que um

dias elas serão pequenas... o que se reflecte hoje no

trânsito caótico de Lisboa.

O novo centro da cidade,

hoje conhecido por baixa pombalina é uma das

atracções turísticas da cidade. São os

primeiros edifícios mundiais a serem construídos com

protecções anti-sismo, que foram testados em modelos de

madeiras à medida que as tropas marchavam ao seu

redor

A competência do

ministro não se limitou à acção de

reconstrução da cidade. O Marquês do Pombal ordenou

um inquérito, enviado a todas as paróquias do país

para apurar a ocorrência e efeitos do terramoto. O

questionário incluía, entre outras

questões:

Quanto tempo durou o

terramoto?

Quantas réplicas se sentiram?

Que tipo de danos causou o terramoto?

Os animais tiveram comportamentos estranhos? (esta questão

antecipou estudos sismológicos chineses, da década de

1960)

Que aconteceu nos poços?

As respostas estão

ainda arquivadas na Torre do Tombo. Através das respostas do

inquérito foi possível aos cientistas actuais recolherem

dados fiáveis e reconstituírem o fenómeno de uma

perspectiva científica. O inquérito do Marquês do

Pombal foi a primeira iniciativa de descrição objectiva

no campo da sismologia, razão pela qual o Marquês do

Pombal é considerado um percursor da ciência da

sismologia.

As causas geológicas

do terramoto e da actividade sísmica na região de Lisboa

são ainda causa de debate científico. Apesar de existirem

indícios geológicos da ocorrência de grandes abalos

sísmicos com a periodicidade de aproximadamente 300 anos,

Lisboa encontra-se no centro de uma placa tectónica, não

existindo assim justificação para um terramoto tão

intenso. Alguns geólogos avançam que o terramoto

estará relacionado com o desenvolvimento de uma zona de

subducção no Oceano Atlântico, e com o início

do fecho deste oceano.

.

.  .

.

Letter from James

O’Hara

Lisbon, November 12, 1755

"Dear

sister,

I sit down to relate to you the dreadful catastrophe that has

befallen the once-flourishing city of Lisbon, now a scene of horror

and desolation.

On the first day

of this month, at half past nine in the forenoon, a sudden

earthquake shook its foundations, and laid it in ruins. At this

fatal hour, the churches were crowded; and as their fall was

momentary, and allowed no time for retreating, those who were in

them were crushed to death.

It is impossible to describe the affrighted looks of the

inhabitants, flying various ways to avoid destruction. Numbers

flocked to the river’s side in hopes to save their lives by

means of boats. The custom-house quay was imagined to be a place

for safety; but unhappily it was soon inundated, and those who fled

on it, only escaped from the falling city, to meet a watery grave.

Fathers and mothers were seen seeking their children, and children

searching for their parents."

The 1755 Lisbon earthquake

took place on November 1, 1755, at 9:20 in the morning. It was one

of the most destructive and deadly earthquakes in history, killing

well over 100,000 people. The quake was followed by a tsunami and

fire, resulting in the near total destruction of Lisbon. The

earthquake accentuated political tensions in Portugal and

profoundly disrupted the country's 18th century colonial ambitions.

The event was widely discussed by European Enlightenment

philosophers, and inspired major developments in theodicy and in

the philosophy of the sublime. The first to be studied

scientifically for its effects over a large area, the quake

signaled the birth of modern seismology. Geologists today estimate

the Lisbon earthquake approached magnitude 9 on the Richter

scale.

The earthquake struck on the morning of November

1, the All Saints' Day Catholic holiday. Contemporary reports state

that the earthquake lasted between three-and-a-half and six

minutes, causing gigantic fissures five meters wide to rip apart

the city center. The survivors rushed to the open space of the

docks for safety and watched as the water receded, revealing a sea

floor littered by lost cargo and old shipwrecks. Several tens of

minutes after the earthquake, an enormous tsunami engulfed the

harbor and downtown, rushing up the Tagus river. It was followed by

two more waves. In the areas unaffected by the tsunami, fire

quickly broke out, and flames raged for five days.

The earthquake struck on the morning of November

1, the All Saints' Day Catholic holiday. Contemporary reports state

that the earthquake lasted between three-and-a-half and six

minutes, causing gigantic fissures five meters wide to rip apart

the city center. The survivors rushed to the open space of the

docks for safety and watched as the water receded, revealing a sea

floor littered by lost cargo and old shipwrecks. Several tens of

minutes after the earthquake, an enormous tsunami engulfed the

harbor and downtown, rushing up the Tagus river. It was followed by

two more waves. In the areas unaffected by the tsunami, fire

quickly broke out, and flames raged for five days.

Lisbon was not the only

Portuguese city affected by the catastrophe. Throughout the south

of the country, in particular the Algarve, destruction was general.

The shockwaves of the earthquake were felt throughout Europe as far

as Finland and North Africa. Tsunamis up to 20 meters in height

swept the coast of North Africa, and struck Martinique and Barbados

across the Atlantic. A three-meter tsunami hit the southern English

coast.

Of a Lisbon population of

275,000, up to 90,000 were killed. Another 10,000 were killed in

Morocco. Eighty-five percent of Lisbon's buildings were destroyed,

including famous palaces and libraries, as well as most examples of

Portugal's distinctive 16th-century Manueline architecture. Several

buildings that had suffered little damage due to the earthquake

were destroyed by the fire.

It is said that many

animals sensed danger and fled to higher ground before the water

arrived. The Lisbon quake is the first documented reporting of such

a phenomenon in Europe.

The Prime Minister Sebastião de Melo (the

Marquis of Pombal) survived the earthquake and said: “Now?

Bury the dead and feed the living”, and with the pragmatism

that characterized his coming rule, he immediately began organizing

the recovery and reconstruction. He sent firefighters into the city

to extinguish the flames, and ordered teams to remove the thousands

of corpses. Time was short to dispose of the corpses before disease

spread. Contrary to custom and against the wishes of

representatives of the Church, many corpses were loaded onto barges

and buried at sea beyond the mouth of the Tagus. To prevent

disorder in the ruined city, and, in particular, as a deterrent

against looting, gallows were constructed at high points around the

city and at least 34 were executed. The Portuguese Army was

mobilized to surround the city to prevent the able-bodied from

fleeing, so that they could be pressed into clearing the ruins. Not

long after the initial crisis, the prime minister and the King

quickly hired architects and engineers, and less than a year later,

Lisbon was already free from debris and undergoing reconstruction.

The King was keen to have a new, perfectly ordained city. Big

squares and rectilinear, large avenues were the mottos of the new

Lisbon. At the time, somebody asked the Marquis of Pombal the need

of such wide streets. The Marquis answered: one day they will be

small. Indeed, the chaotic traffic of Lisbon today reflects the

wisdom of the reply.

The Prime Minister Sebastião de Melo (the

Marquis of Pombal) survived the earthquake and said: “Now?

Bury the dead and feed the living”, and with the pragmatism

that characterized his coming rule, he immediately began organizing

the recovery and reconstruction. He sent firefighters into the city

to extinguish the flames, and ordered teams to remove the thousands

of corpses. Time was short to dispose of the corpses before disease

spread. Contrary to custom and against the wishes of

representatives of the Church, many corpses were loaded onto barges

and buried at sea beyond the mouth of the Tagus. To prevent

disorder in the ruined city, and, in particular, as a deterrent

against looting, gallows were constructed at high points around the

city and at least 34 were executed. The Portuguese Army was

mobilized to surround the city to prevent the able-bodied from

fleeing, so that they could be pressed into clearing the ruins. Not

long after the initial crisis, the prime minister and the King

quickly hired architects and engineers, and less than a year later,

Lisbon was already free from debris and undergoing reconstruction.

The King was keen to have a new, perfectly ordained city. Big

squares and rectilinear, large avenues were the mottos of the new

Lisbon. At the time, somebody asked the Marquis of Pombal the need

of such wide streets. The Marquis answered: one day they will be

small. Indeed, the chaotic traffic of Lisbon today reflects the

wisdom of the reply.

Pombaline buildings are

among the first seismically-protected constructions in the world.

Small wooden models were built for testing, and earthquakes were

simulated by marching troops around them. Lisbon's "new" downtown,

known today as the Pombaline Downtown (Baixa Pombalina), is one of

the city's famed attractions. Sections of other Portuguese cities,

like the Vila Real de Santo António in Algarve, were also

rebuilt along Pombaline principles.

The Prime Minister's

response was not limited to the practicalities of reconstruction.

The Marquis ordered a query sent to all parishes of the country

regarding the earthquake and its effects. Questions

included:

How

long did the earthquake last?

How many aftershocks were felt?

What kind of damage was caused?

Did animals behave strangely? (this question anticipated studies by

Chinese seismologists in the 1960s)

What happened in wells and water holes?

The answers to these and other questions are

still archived in the Tower of Tombo, the national historical

archive. Studying and cross-referencing the priests' accounts,

modern scientists were able to reconstruct the event from a

scientific perspective. Without the query designed by the Marquis

of Pombal, this would have been impossible. Because the Marquis was

the first to attempt an objective scientific description of the

broad causes and consequences of an earthquake, he is regarded as a

forerunner of modern seismological scientists.

The answers to these and other questions are

still archived in the Tower of Tombo, the national historical

archive. Studying and cross-referencing the priests' accounts,

modern scientists were able to reconstruct the event from a

scientific perspective. Without the query designed by the Marquis

of Pombal, this would have been impossible. Because the Marquis was

the first to attempt an objective scientific description of the

broad causes and consequences of an earthquake, he is regarded as a

forerunner of modern seismological scientists.

The geological causes of

this earthquake and the seismic activity in the region continue to

be discussed and debated by contemporary scientists. Some

geologists have suggested that the earthquake may indicate the

early development of an Atlantic subduction zone, and the beginning

of the closure of the Atlantic Ocean.

A

cache:

ATENÇÃO: Esta cache, em

memória do 250º aniversário do terramoto de 1755, em

Lisboa, será activada apenas no

dia comemorativo desse fatídico acontecimento, 1 de Novembro

de 2005.

Nesta mesma ocasião, entre 1

e 4 de Novembro, decorrerá em Lisboa uma conferência

internacional comemorativa deste acontecimento, intitulada "250th Anniversary of the 1755 Lisbon

Earthquake”.

A cache encontra-se

escondida em frente ao Centro Cultural de Belém, onde

será realizada a sessão de abertura da referida

conferência, na zona ribeirinha que tanto foi afectada pelo

terramoto e consequente maremoto. Por favor seja discreto na busca

e volte a colocar o recipiente como o encontrou, para que fique bem

preso e não seja encontrado por terceiros.

The

cache:

NOTE: This cache, to commemorate the

250th anniversary of the 1755 Lisbon earthquake, will be activated only on the 1st of November

2005, 250 years after this catastrophic day.

At the same time, between 1 and 4 November, there will be in Lisbon

an international conference commemorating this seismic event

entitled “250th Anniversary of the 1755 Lisbon

Earthquake”.

The cache is

hidden in front of the Centro Cultural de Belém, where the

opening session and the first lectures of the conference will be

carried through, in the marginal zone that was so affected by

earthquake and consequent tsunami. Be very discrete in your search

and please put the container back in the position as you found it,

so that it is well attached and not easilly found by

“muggles”.