BELLE ROCHE

FRANCAIS

-

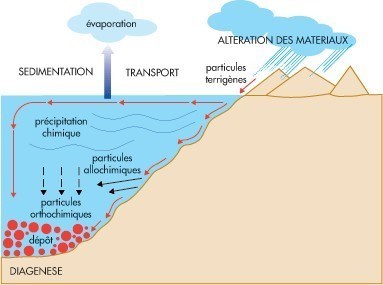

Formation des roches sédimentaires

Les roches sédimentairessont celles qui se forment à la surface de la Terre par accumulation de sédiments, le plus généralement au fond de l'eau : en mer, dans un lac, une lagune, ou dans un delta, mais parfois aussi en milieu terrestre aérien, à la surface des continents, comme d’anciennes moraines, par exemple. De par leur origine externe, les roches sédimentaires s'opposent donc aux roches d'origine profonde, magmatiques ou

métamorphiques. Les roches sédimentaires ne représentent que environ 5 % du volume de la croûte terrestre, cependant elles en recouvrent 75 % de la surface, et sont donc très présentes dans les paysages.

La diagenèse désigne l'ensemble des processus physico-chimiques et biochimiques par lesquels les sédiments sont transformés en roches sédimentaires. Ces transformations ont généralement lieu à faible profondeur, donc dans des conditions de pression et température peu élevées.

2. Formation des grès

2. Formation des grès

Les grès sont des roches sédimentaires détritiques composées d’une grande majorité de grains de quartz. Ils proviennent de la consolidation d’un ancien sable meuble. Cette diagenèse s’opère par circulation d’eau, dépôt d’un ciment naturel entre les grains et compaction. Cette cimentation progressive peut combler en totalité ou seulement en partie les espaces entre les grains. De ce fait, certains grès conservent une porosité importante. La nature du ciment qui lie les grains varie d’un grès à un autre : siliceux,calcaire, ferrugineux…Les arkoses sont des grès riches en feldspaths. Les grès très riches en quartz et très durs sont souvent qualifiés de grès quartziques.

A l'époque du Trias, les eaux, qui circulent au travers des alluvions et des grains de sable, déposent un ciment siliceux qui contribue à l'induration du matériau, c'est à dire à la transformation des sables en grès. De la même manière se met en place le pigment rouge, un oxyde de fer, responsable de la coloration du grès. En effet, l'altération de minéraux initialement riches en fer comme le mica noir ou la magnétite, libère

leur fer qui migre vers les grains voisins et les teintes d'une fine pellicule rose lorsque le

milieu est bien oxygéné. C'est le phénomène de rubéfaction, un processus qui se produit

tout au long de l'enfouissement du sédiment. Maintenant on observe des niveaux de grès encore gris tandis que d'autres ont déjà viré au rose où ont des teintes panachées, c'est qu'ils ont manqué d'oxygène au moment de leurs formations (eau stagnante par exemple). C'est pour cette raison que les formations gréseuses sont nommées en Europe

Buntsandstein, c'est à dire "grès bigarrés".

Les géologues rapportent le Buntsandstein au début de l'ère secondaire, à une période de l'histoire de la terre appelée Trias inférieur entre -250 et -240 millions d'années. Les sables associés à des galets parcours notre région dans des grands fleuves vers la mer Germanique. Ces grès correspondent à

d'anciens bancs d'alluvions déposés dans des cours d'eau lors des crues. Les galets sont semblables à ceux que l'on trouve dans les torrents de montagne

aujourd'hui.

-

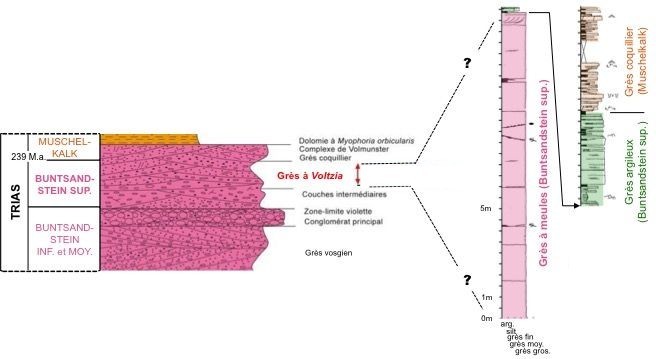

Les différents grès du Trias inférieur

Près de 300 millions d'années se sont donc écoulées depuis l'édification de la chaîne hercynienne. L'épaisse formation de grès, qui résulte de son érosion, est caractérisée par une succession de périodes, ou les conditions de sédimentations diffèrent. La série du Buntsandstein est essentiellement constituée par des grès rouge sombre à l'état humide ou rose à l'état sec.

Il couvre de grandes étendues dans le Palatinat Allemand. Des formations de grès de même âge se rencontrent également dans la région de Saint-Dié et sont connus sous le nom de grès de Senones. Il est rouge violacé et friable.

Localement l'épaisseur est de 300m pour ce grès de couleur lie de vin nuancé en rouge brique, blanche ou jaune. Il constitue l'ensemble de la base des rochers des Vosges du Nord. Il consiste en un grès grossier, de grains de quartz avec une proportion assez variable de feldspaths (5 à 25%). Les

grains sont de formes très arrondies et enduites d'un pigment ferrugineux. La cimentation s'est faite par nourrissage des grains, soit du grain entier, soit par des excroissances en fins éléments microscopiques cristallisés (cristallites) formant des ponts entre les grains. Des galets durs de quartzite grise et de quartz filonien blanc sont disséminés.

Dans tout le massif Vosgien, les grès Vosgiens sont surmontés par le conglomérat principal aussi appelé Poudingue de Sainte Odile. L'épaisseur est en moyenne de 15m et il affleure souvent en corniches rocheuses ou en de vastes rochers couronnant les collines (exemple du Sainte Odile, Haut Barr ou Dabo). Il est très grossier et très chargé en galets de quartz (60 à 70%) et de quartzite (30 à 40%) dont la taille moyenne est de 2 cm.

D'une épaisseur de 80m environ, ces grès deviennent plus fins et les intercalations argileuses gagnent en importance. Il est d'une teinte rouge sombre à lie de vin et les galets disséminés sont beaucoup plus petits que ceux du grès Vosgien ou du conglomérat. La stratification est horizontale, oblique ou entrecroisée.

L'épaisseur de cette couche de grès avoisine les 20m par endroit, il est aussi appelé :

o"grès à meules" pour sa partie inférieure de couleur gris à rose.

o "grès argileux" pour sa partie supérieure de couleur rouge ou bariolé vert et gris.

Il est très riche en reste de plantes comme les conifères (genre Voltzia) et il comporte un grain fin.On reconnaît comme pour le grès Vosgien les deux catégories de dépôts typiques d'une plaine alluviale, ceux des chenaux fluviatiles et ceux de la plaine d'inondation malgré le fait que les plages et le littoral de la mer Germanique soit proche. La stratification est oblique à horizontale.

Son grain fin et son manque de galet lui donne des facilités pour la taille, et la cathédrale deStrasbourg en est une remarquable illustration.

Petit à petit les niveaux carbonatés deviennent de plus en plus importants et la faune s'affirme typiquement marine. Beaucoup de fossiles sont emprisonnés dans cette couche de grès constitué de batraciens et de débris végétaux. Le grès devient jaunâtre, il est friable et peu épais (20cm), on l'appelle le grès coquillier. La mer a alors envahit le delta. C'est la fin de la formation des grès, maintenant durant le Trias moyen, ce sont les calcaires du Muschelkalk qui vont se former.

Cette "Belle Roche" permet de visualiser bon nombre de dégradations compte tenu de son age. Depuis 200 ans, ce rocher subit les assauts du climat.

4) Les altérations du grès avec détérioration de sa valeur

Les atteintes du grès qui provoquent une perte d'intégrité fonctionnelle et/ ou décorative ont différentes origines, souvent issues d'une addition de facteurs environnementaux, des propriétés du matériau et de sa mise en œuvre. On distingue ainsi plusieurs familles d'altérations dans lesquelles les principales figures sont :

Les fissures qui regroupent :

Les détachements qui sont composés :

-

de boursouflures ou cloques (souvent en lien avec la présence de sels)

-

de l'éclatement induit par exemple par la corrosion des agrafes ou goujons

-

du délitage du grès

-

de exfoliation

-

de la désagrégation sableuse

-

de la fragmentation, consécutive le plus souvent à une surcharge

-

de la desquamation caractérisé par la faible épaisseur de perte de matière

-

du détachement ou desquamation en plaque, quant celle-ci reproduit le modelé de la pierre, parallèlement à sa surface.

Les figures induites par une perte de matière avec :

-

l'érosion

-

l'alvéolisation ou creusement

-

les dégâts mécaniques (dus à une action non naturelle)

-

la perforation ou percement

-

les piqûres ou cavités

-

les parties manquantes.

Les altérations chromatiques et dépôts dont :

-

les croûtes noires (particules atmosphériques piégées dans du gypse qui se développent à l'abri de la pluie)

-

les croûtes salines (composées de sels solubles)

-

les encroûtements ou concrétion issus du lessivage des matériaux par les eaux de pluie

-

les efflorescences (cristaux de sels principalement blancs localisés en surface)

-

les subflorescences (cristaux de sels sous la surface de la pierre).

L'alvéolisation qui désigne le phénomène de formation des alvéoles nécessite l'interaction de plusieurs facteurs : une roche poreuse qui autorise la circulation de l'eau et des ions dissous, une surface exposée au soleil (aidé par le vent) qui favorise l'évaporation de l'eau de la roche et par ce biais la cristallisation des sels entre les grains. La croissance cristalline crée une pression qui rompt l'assemblage initial des grains de la roche.

5) Les altérations du grès sans dégradations

Le grès se modifie superficiellement de façon naturelle mais aussi parfois par l'action de l'Homme. Dans la plupart des cas, ces changements n'entraînent pas de dégradations du matériau.

Les figures d'altérations rencontrées sont d'ordres chromatique et de dépôt avec notamment :

-

les dépôts matérialisés par une accumulation de matériaux exogènes comme par exemple les fientes de pigeons ou les salissures de mortier

-

les encrassements constitués par des dépôts très fins comme les poussières et les suies

-

les changements de couleur du grès liés par exemple à l'humidité ou à l'oxydation de métaux (fer, cuivre, etc.)

-

les graffitis par application de peinture ou d'encre, d'incision et de rayure

-

les patines artificielles

Le cas particulier de la patine noire vernissée

Le grès dans son environnement, extrait de carrière, se patinera naturellement. Comme pour le bois manufacturé et les tanins qui vont se griser naturellement et superficiellement, les qualités intrinsèques sont peu impactées voire, pas affectées.

La patine noire vernissée ou patine ferrugineuse se forme principalement à partir des oxydes de fer contenus dans les grès et dans les zones exposées aux intempéries. L'altération chromatique induite est, dans la majorité des cas, une fine couche protectrice de couleur noire. Il ne faut pas la confondre avec les croûtes noires qui sont des concrétions salines sources de détériorations.

Cette patine est une évolution naturelle et fait partie de la nature du grès, ce n'est en aucun cas une "maladie", nous la conservons dans la plupart des cas.

La colonisation biologique

Donnant l'aspect d'une altération (développement végétal avec les plantes, mousses et les microorganismes/ bactéries avec les algues, moisissures et lichens), des modifications de surface (le grès est un support de développement) peuvent dans certaines conditions d'exposition et d'humidité, engendrer des dégradations. Elles peuvent occasionner des détériorations allant du simple dessertissage des grains à l'apparition de cavités, voire des fracturations de joints et du grès dans le cas de systèmes racinaires conséquents.

La biodiversité animale peut impacter indirectement l'édifice par les nids et les déjections.

Questions:

Question 1: Definissez ce qu'est une roche sédimentaire

Question 2: Qu'est ce qu'est la diagenèse ?

Question 3: Determinez les grandes familles d'altérations avec perte de matière ?

Queston 4: Comment et quand se sont formès les grès dans les Vosges ?

Question 5: A quel type de grès avons nous affaire ici? Justifiez votre réponse.

Question 6 . Definissez les différents types d'altérations visibles sur le rocher au niveau des zones sculptées.

Question 7. Determinez précisemment les altérations visibles au niveau de la sculpture de Saint Pierre.

Question 8.Une photo de vous près du rocher serait appréciée (optionnel)

Loguez cette cache en found it et envoyez moi vos réponses via mon profil ou via le centre de messagerie geocaching.com et je vous contacterai en cas de problème .

ANGLAIS

BELLE ROCHE

1) Formation of sedimentary rocks

Sedimentary rocks are those that form on the Earth's surface by sediment accumulation, most commonly at the bottom of the water: at sea, in a lake, in a lagoon, or in a delta, but sometimes also in aerial land. on the surface of continents, like ancient moraines, for example. Because of their external origin, the sedimentary rocks are thus opposed to rocks of deep origin, magmatic or

metamorphic. Sedimentary rocks represent only about 5% of the volume of the earth's crust, yet they cover 75% of the surface, and are therefore very present in landscapes.

Diagenesis refers to all the physicochemical and biochemical processes by which sediments are transformed into sedimentary rocks. These transformations generally take place at shallow depth, therefore under conditions of low pressure and low temperature.

2) Formation of sandstone

Sandstones are detrital sedimentary rocks composed of a great majority of quartz grains. They come from the consolidation of an old loose sand. This diagenesis takes place by circulation of water, deposition of a natural cement between the grains and compaction. This progressive cementation can fill all or only part of the spaces between the grains. As a result, some sandstones retain significant porosity. The nature of the cement that binds the grains varies from one sandstone to another: siliceous, calcareous, ferruginous ... The arkoses are sandstones rich in feldspars. Sandstones very rich in quartz and very hard are often called quartz sandstones.

At the time of the Triassic, the waters, which circulate through alluviums and grains of sand, deposit a siliceous cement which contributes to the induration of the material, that is to say to the transformation of the sands in sandstone. In the same way, the red pigment, an iron oxide, which is responsible for the coloring of the sandstone, is put in place. In fact, the alteration of minerals initially rich in iron, such as black mica or magnetite, releases

their iron that migrates to the neighboring grains and the hues of a thin pink film when the

middle is well oxygenated. This is the phenomenon of reddening, a process that occurs

throughout the burial of the sediment. Now we observe levels of sandstone still gray while others have already turned pink where have variegated hues, it is that they ran out of oxygen at the time of their formations (stagnant water for example). It is for this reason that sandstone formations are named in Europe

Buntsandstein, ie "variegated sandstone".

Geologists report Buntsandstein at the beginning of the secondary era, at a period of history called Lower Triassic Earth between -250 and -240 million years ago. The sands associated with pebbles course our region in great rivers towards the Germanic sea. These sandstone correspond to

old banks of alluvium deposited in rivers during floods. The pebbles are similar to those found in mountain streams

today.

3) The different sandstones of the lower Triassic

Nearly 300 million years have passed since the construction of the Hercynian chain. The thick sandstone formation, which results from its erosion, is characterized by a succession of periods, where sedimentation conditions differ. The Buntsandstein series consists essentially of dark red sandstones in the wet or dry pink state.

The lower Buntsandstein: The Annweiler sandstone

It covers large expanses in the German Palatinate. Sandstone formations of the same age are also found in the region of Saint-Die and are known as sandstone Senones. It is purplish red and friable.

The Middle Buntsandstein: The Vosges Sandstone

Locally the thickness is 300m for this colored sandstone wine color nuanced in red brick, white or yellow. It constitutes the whole of the base of the rocks of the Vosges du Nord. It consists of coarse sandstone, quartz grains with a fairly variable proportion of feldspars (5 to 25%). The

grains are of very rounded forms and coated with ferruginous pigment. Cementation was done by feeding grain, either whole grain, or by excrescences in fine crystallized microscopic elements (crystallites) forming bridges between the grains. Hard pebbles of gray quartzite and white vein quartz are disseminated.

The main conglomerate

Throughout the Vosges mountains, the Vosges sandstone is surmounted by the main conglomerate also called Poudingue de Sainte Odile. The thickness is on average 15m and it often outcrops in rocky ledges or large rocks crowning the hills (example of Sainte Odile, Haut Barr or Dabo). It is very coarse and heavily loaded with quartz pebbles (60 to 70%) and quartzite (30 to 40%) with an average size of 2 cm.

The upper Buntsandstein: The intermediate layers

With a thickness of approximately 80m, these sandstones become thinner and the clay intercalations become more important. It is a dark red hue with wine lees and scattered pebbles are much smaller than those of the Vosges sandstone or conglomerate. The stratification is horizontal, oblique or intersecting.

The Upper Buntsandstein: Sandstone in Voltzia

The thickness of this layer of sandstone is around 20m in places, it is also called:

o "stoneware" for its lower part of gray to pink color.

o "clay sandstone" for its upper part of red color or green and gray variegated.

It is very rich in remains of plants such as conifers (genus Voltzia) and it has a fine grain. As for the Vosgian sandstone, we recognize the two categories of deposits typical of an alluvial plain, those of river channels and those of the plain. in spite of the fact that the beaches and the coastline of the Germanic Sea are close. The stratification is oblique to horizontal.

Its fine grain and lack of pebble gives it facilities for the size, and the Cathedral of Strasbourg is a remarkable illustration.

Gradually the carbonate levels become more and more important and the fauna asserts itself typically marine. Many fossils are trapped in this layer of sandstone consisting of amphibians and plant debris. The sandstone becomes yellowish, it is friable and not thick (20cm), it is called shellfish sandstone. The sea then invaded the delta. This is the end of the sandstone formation, now during the Middle Triassic, it is the limestones of the Muschelkalk that will be formed.

This "Beautiful Rock" allows to visualize many degradations considering its age. For 200 years, this rock has suffered the onslaught of the climate.Sandstone alterations with deterioration of value

4) Sandstone impacts that cause a loss of functional and / or decorative integrity have different origins, often resulting from an addition of environmental factors, properties of the material and its implementation. We thus distinguish several families of alterations in which the main figures are:

The cracks that group:

thinner openings with cracks and microcracks

the cleavages

fractures

star cracking that comes from corrosion of staples and studs.

Detachments that are composed of:

blisters or blisters (often related to the presence of salts)

the burst induced for example by the corrosion of the staples or studs

sandstone disintegration

exfoliation

sandy weathering

fragmentation, usually resulting from overloading

desquamation characterized by the small thickness of material loss

detachment or desquamation in plate, as this reproduces the model of the stone, parallel to its surface.

The figures induced by a loss of material with:

erosion

honeycombing or digging

mechanical damage (due to unnatural action)

perforation or piercing

bites or cavities

the missing parts.

Chromatic alterations and deposits including:

Black crust (atmospheric particles trapped in gypsum that develop in the shelter of the rain)

saline crusts (composed of soluble salts)

crusts or concretion resulting from the leaching of materials by rainwater

efflorescence (mainly white salt crystals located on the surface)

subflorescences (salt crystals under the surface of the stone).

Alveolization, which refers to the phenomenon of cell formation, requires the interaction of several factors: a porous rock that allows the circulation of water and dissolved ions, a surface exposed to the sun (helped by the wind) which favors the evaporation of the water from the rock and through this the crystallization of the salts between the grains. The crystalline growth creates a pressure which breaks the initial assembly of the grains of the rock.

5) Sandstone alterations without damage

Sandstone is superficially modified in a natural way but also sometimes by the action of Man. In most cases, these changes do not cause damage to the material.

The figures of alterations encountered are of chromatic order and of deposit with notably:

deposition materialized by an accumulation of exogenous materials such as pigeon droppings or mortar soils

fouling consisting of very fine deposits such as dust and soot

the color changes of the sandstone related for example to the humidity or the oxidation of metals (iron, copper, etc.)

graffiti by applying paint or ink, incision and scratch

artificial patinas

The special case of the black glazed patina

The sandstone in its environment, extracted from quarry, will skate naturally. As for manufactured wood and tannins that will get intoxicated naturally and superficially, the intrinsic qualities are little impacted or even not affected.

The glazed black patina or ferruginous patina is formed mainly from the iron oxides contained in sandstones and in areas exposed to the weather. The induced chromatic alteration is, in the majority of cases, a thin protective layer of black color. It should not be confused with black crusts that are saline concretions causing deterioration.

This patina is a natural evolution and is part of the nature of sandstone, it is by no means a "disease", we keep it in most cases.

Biological colonization

Giving the appearance of an alteration (plant development with plants, mosses and microorganisms / bacteria with algae, molds and lichens), surface modifications (sandstone is a development medium) can under certain conditions of exposure and humidity, generate degradations. They can cause deteriorations ranging from simple unfinishing grain to the appearance of cavities, or even fractures joints and sandstone in the case of consistent root systems.

Animal biodiversity can indirectly impact the building through nests and droppings.

Questions:

Question 1: Define what is a sedimentary rock

Question 2: What is diagenesis?

Question 3: Determine the major families of alterations with loss of material?

Queston 4: How and when did the sandstones form in the Vosges?

Question 5: What type of sandstone do we have here? Justify your answer.

Question 6. Define the different types of alterations visible on the rock at the sculpted areas.

Question 7. Determine clearly the alterations visible in the sculpture of Saint Peter.

Question 8.A photo of you near the rock would be appreciated (optional)

Log this cache in found it and send me your answers via my profile or via the geocaching.com messaging center and I will contact you in case of problems.