Français

INTRODUCTION

La base et les terrils jumeaux du 11/19 constituent l’un des quatre grands sites du patrimoine minier conservés dans le Nord-Pas de Calais.

Ces deux chiffres 11 et 19 font référence aux numéros des anciens puits de mine, 11 pour le chevalement métallique des années 1920 et 19 pour la tour de concentration en béton de 1960.

Le site présente l’avantage d’offrir une vision quasi-complète de ce que pouvait être un site minier avec le carreau de fosse, les terrils (résidus de l’exploitation du charbon) et la cité minière où logeaient les ouvriers.

LE TERRIL

Un terril est un entassement de déchets miniers à ciel ouvert, la plupart du temps issus de l’extraction du charbon. Ce terme proviendrait du mot wallon « terri » qui qualifie un amas de terre et de pierre.

Concrètement, un terril est principalement composé de sous-produits de l’exploitation minière, à savoir des schistes, des grès carbonifères et d’autres résidus mais il contient également des restes de houille.

Les terrils n’ont pas toujours eu la forme conique à laquelle on les associe fréquemment. Les premiers d’entre eux, apparus dans les années 1850, étaient plats : les résidus miniers étaient alors transportés hors des galeries au moyen de paniers, puis plus tard par un système de wagonnets et déposés à proximité de la mine. C’est à partir de la fin du XIXe siècle que sont apparues, grâce à la mécanisation, les premières collines artificielles de résidus miniers : les terrils étaient alors édifiés par rampes ou par déversement de déchets à leur sommet.

Outre leur forme, les terrils sont parfois classifiés dans les catégories suivantes : terril « monumental » (au regard de leur surface et de leur volume), terril « signal » (visible à plus de 15 km), terril « mémoire » (lié à un événement historique), terril « nature » (recouvert d’éléments végétaux) ou encore terril « loisirs » (support à des activités comme du ski sur le terril 42 de Nœux-les-Mines).

LES FOSSILES

Les schistes noirs du terril font le bonheur des amateurs de fossiles.

On trouve en effet assez facilement des empreintes de troncs, de tiges et de feuilles imprimées sur les pierres extraites de la mine.

C'est l'occasion de se souvenir que la formation du charbon date de plus de 300 millions d'années, à l'époque où une forêt tropicale recouvrait la région.

Ici plus précisément, d'énormes quantités de végétaux se sont accumulées dans des lagunes d'eau peu profonde, où elles ont échappé à l'action des décomposeurs.

Au fil de processus chimico-physiques longs et complexes, les débris se sont transformés en roche sédimentaire combustible.

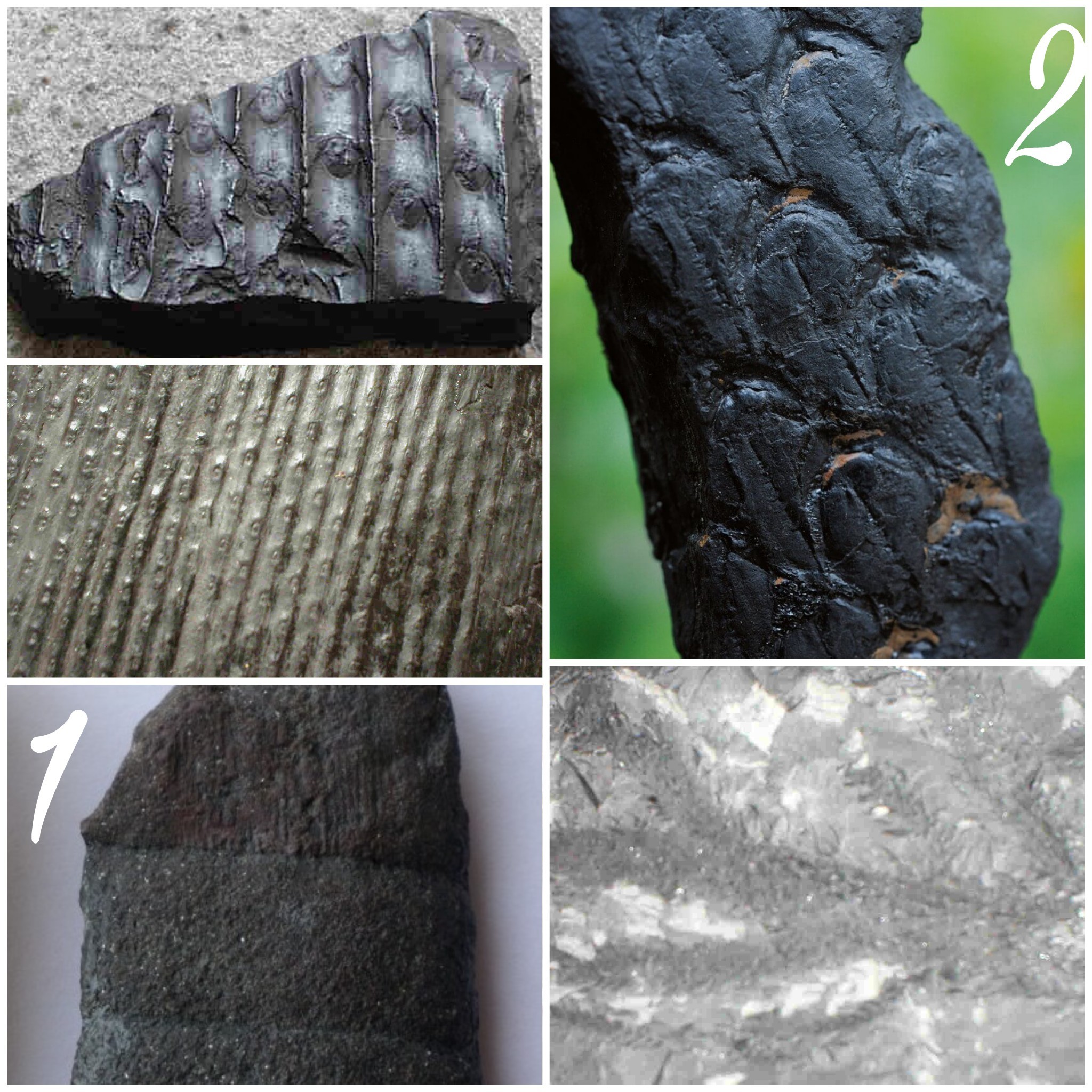

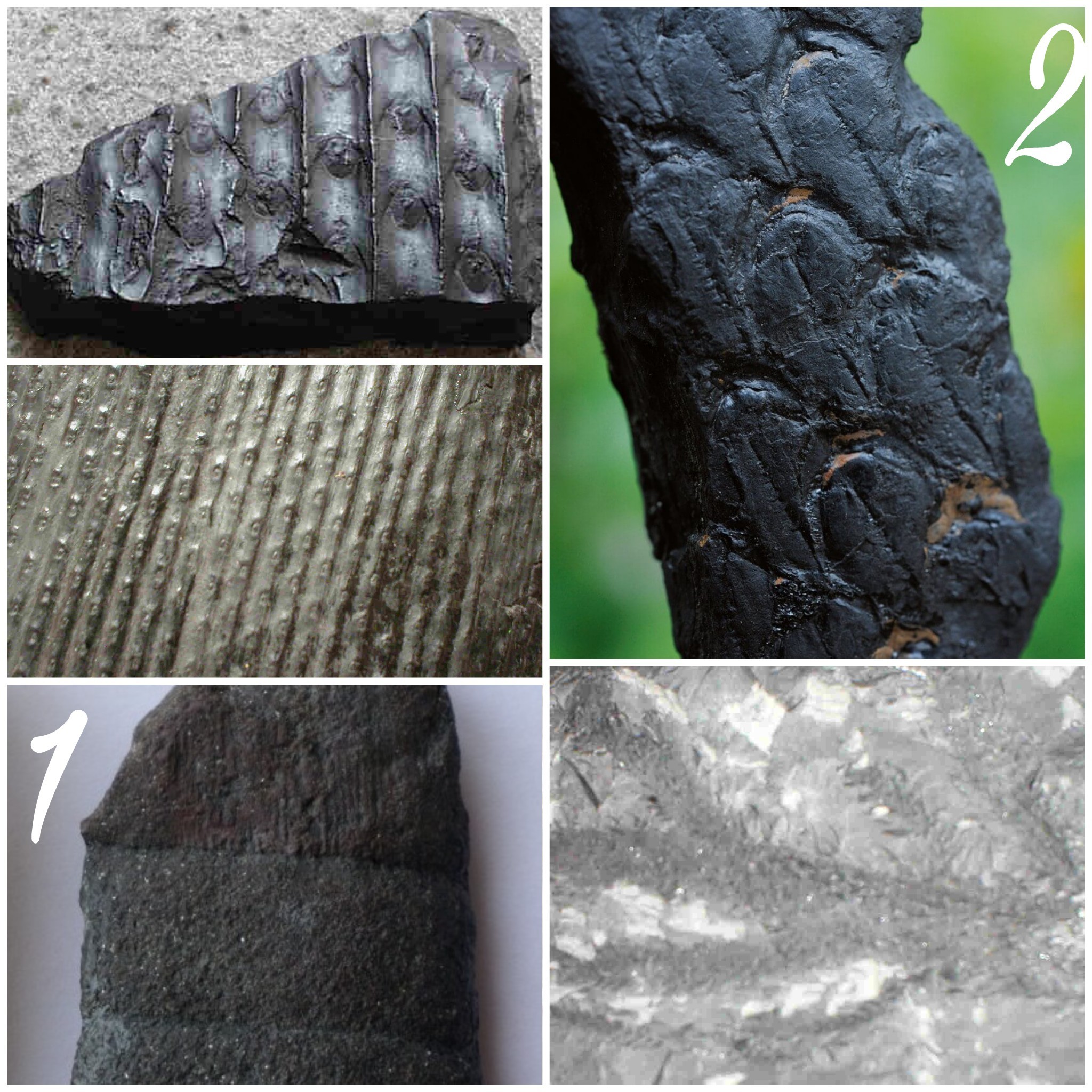

Exemple de fossiles miniers

LA COMBUSTION DU TERRIL

La PYRITE DE FER est un minéral appelé l’or des fous car il brille. Dans le sous-sol, il est à l’abri de la lumière, de l’eau et du dioxygène.

Quand il se retrouve dans le terril, il se produit une réaction exothermique, il y a donc production de chaleur. Les réactions avec le dioxygène et l’eau engendrent un dégagement de chaleur qui brûle ce qui l’entoure (bois, charbon…). Il y a alors la possibilité d’une combustion interne au cœur du terril s’il est assez riche en charbon. Cela peut engendrer des températures entre 400° et 700°C. S’il y a des déchets dans ce terril, ils peuvent alors brûler et engendrer des dégâts importants autour du terril.

Il peut se dégager des terrils de la fumée, c’est de la vapeur d’eau créé du fait de la chaleur des réactions exothermiques sur l’eau d’infiltration des pluies.

La combustion lente de certains terrils (voir ci-dessus) est la cause d'un phénomène de vitrification des schistes qui acquièrent ainsi des capacités mécaniques suffisantes pour en faire des matériaux de construction routière.

Certains connaissent donc une seconde vie en étant exploités dans ce but.

Rappel concernant les « Earthcaches »:

Il n'y a pas de conteneur à rechercher ni de logbook à renseigner. Il suffit de se rendre sur les lieux et d'exécuter les requêtes du propriétaire de la cache avec l'envoi des réponses par mail pour validation. Bon Earthcaching!

Pour valider votre visite:

Waypoint 1 :

1-. Que voit-on de particulier sur le terril de droite ? Que peut-on alors en déduire quant au mode d’édification du terril ?

2-. Quelle est la forme des terrils jumeaux ? Donnez les 2 raisons qui expliquent leur forme (une explicitée dans le texte, l’autre plus difficile à trouver et qui est particulière à Loos en Gohelle) ?

Waypoint 2 :

3-. De ce point ou quelques pas en avant, que voyez vous au pied du terril ? Quelle conclusion en tirez-vous ?

Sur site:

4-. Sur les terrils jumeaux, on trouve notamment les 2 fossiles numérotés 1 & 2 sur la photo du texte. Quels sont-ils ?

5-. Un arbre peu commun dans la région pousse sur le terril (le figuier). Comment expliquez vous cette improbabilité ?

6-. AU PZ N50°26.700 E002°47.174, il y a un panneau indicatif avec le fameux point rouge "vous êtes ici", Qu'est-il écrit en blanc juste au dessus de ce point ?

vous pouvez joindre à votre log une photo (non obligatoire)

English

INTRODUCTION

The base and the twin slag heaps of 11/19 are one of the four main mining heritage sites preserved in Nord-Pas de Calais. These two numbers 11 and 19 refer to the numbers of the old mine shafts, 11 for the metal headframe of the 1920s and 19 for the concrete concentration tower of 1960. The site has the advantage of offering an almost complete vision of what could be a mining site with the pit tile, the heaps (residues of coal mining) and the mining town where the workers lived.

THE SLAG HEAPS

Slag heaps are a pile of open pit mining waste, mostly from coal mining. This term comes from the Walloon word "terri" which describes a pile of earth and stone.

Specifically, a slag is mainly composed of by-products of mining, namely schist, carbonaceous sandstone and other residues but it also contains remnants of coal.

The heaps have not always had the conical shape to which they are frequently associated. The first of these, which appeared in the 1850s, were flat: the tailings were then transported out of the galleries by means of baskets, and later by a system of carriages and deposited near the mine. It was from the end of the 19th century that, thanks to mechanization, the first artificial hills of mining residues appeared: the heaps were then built by ramps or by dumping waste at their summit.

In addition to their shape, slag heaps are sometimes classified in the following categories: "monumental" heap (with regard to their surface and volume), "signal" heap (visible more than 15 km away), "memory heap" (linked to a historical event), terril "nature" (covered with plant elements) or heap "recreation" (support for activities such as skiing on the terril 42 of Nœux-les-Mines).

FOSSILS

The black shales of the heap make the happiness of the amateurs of fossils.

Trunk impressions, stems and leaves printed on the stones extracted from the mine are quite easily found.

This is an opportunity to remember that the formation of coal dates back more than 300 million years, at a time when a tropical forest covered the region.

Here more precisely, enormous amounts of vegetation have accumulated in shallow water lagoons, where they have escaped the action of decomposers.

In the course of long and complex chemical-physical processes, the debris has been transformed into combustible sedimentary rock.

Example of mining fossils

THE HEAP’S COMBUSTION

The IRON PYRITE is a mineral called crazy gold because it shines. In the basement, it is protected from light, water and oxygen.

When it is in the heap, there is an exothermic reaction, so there is heat production. The reactions with the oxygen and the water generate a release of heat which burns what surrounds it (wood, coal ...). There is then the possibility of an internal combustion in the heart of the heap if it is quite rich in coal. This can cause temperatures between 400 ° and 700 ° C. If there is waste in this heap, then they can burn and cause significant damage around the heap.

It can emerge from smoke dumps, it is water vapor created due to the heat of the exothermic reactions on the seepage water of the rains.

The slow combustion of some slag heaps (see above) is the cause of a phenomenon of vitrification of schists which thus acquire sufficient mechanical capacities to make road construction materials.

Some know a second life being exploited for this purpose.

Reminder on "Earthcaches":

There is no container or logbook on the given coordinates. Just visit the site and answer the questions by e-mail to validate. Happy caching!

To validate your visit:

Waypoint 1 :

1-. What do we see in particular on the heap on the right? What can we then deduce from it as to the mode of construction of the heap?

2-. What is the shape of twin slag heaps? Give the 2 reasons that explain their form (one explained in the text, the other more difficult to find and which is particular to Loos in Gohelle)?

Waypoint 2 :

3-. From this point or a few steps forward, what do you see at the foot of the heap? What conclusion will you make of it?

On the spot:

4-. On the twin slag heaps, we find in particular the 2 fossils numbered 1 & 2 on the photo of the text. What are they ?

5-. An unusual tree in the area grows on the heap (fig tree). How do you explain this improbability?

6-. AT PZ N50 ° 26.700 E002 ° 47.174, there is an indicative sign with the famous red dot "Vous êtes ICI", What is written in white just above this point? you can attach a photo to your log (not required)