Please note that the industrial archaeological landscape around Haytor is protected, with the tramway itself being a Scheduled Ancient Monument (SAM). The area around the granite outcrop of Haytor itself, including this quarry, is also an SSSI for geological reasons. It is illegal to wilfully damage the area in any way so please be respectful of this wonderful heritage and geological asset.

Granite, which is synonomous with Dartmoor, is almost everywhere you look. It makes up much of the bedrock of the national park and has helped form the tors. But beyond this granite is much more intrinsic in the creation of the upland area of Dartmoor. Most of the higher parts of the Moor are made up of granite geology. This is because granite is very resistant to weathering so the land around the upland area of Dartmoor has weathered down over centuries, leaving the granite core of Dartmoor standing high above the surround area.

As well as creating the wonderful upland area of Dartmoor the geology has also led to a significant amount of the areas industrial wealth throughout history. The rich arrays of metals, such as iron, uranium and tin have long been exploited leaving many areas, such as Ivy Tor just up the River Taw, pot marked as a result of extraction. The granite too has created industrial possibilities. As it decays it breaks down into China Clay, which as its name suggests has extracted in Britain since the mid 18th century to make fine china. But by far the longest and most extensively exploited of the areas resources is the 'raw' granite itself.

Granite has been used for over 4000 years. It was used during the late Neolithic and the early Bronze Age as a key building material. During the late Neolithic and early Bronze Age ceremonial complexes, including stone rows and circles, were constructed using the abundant granite. Later during the Bronze Age granite was used to create the thousands of hut circles, enclosures and field boundaries (Reaves) that again can be seen all over Dartmoor. Despite the long history of granite being used it wasn't until the 19th century that Dartmoor granite was extracted commercially.

The first documented quarrying of granite on Dartmoor was the opening of a small quarry to extract material to construct Dartmoor Prison in 1806-9. But the quarries around Haytor, as well as being subjectively the most impressive and best surviving, were the first true commercial quarries, opened in c.1820. The land owner at the time, George Templer, devised a plan for transporting the extracted material that is a real feat of engineering and daring, which still survives today. This is the famous tramway that connected the quarries to the canal at Ventiford. This tramway was even built out of the granite, which is the reason that in large sections at Haytor, the original tramway can be seen today. Through historical work it is thought that the quarries were mainly opened to supply building material for the construction of London Bridge, amongst others building works. The quarry complex at Haytor consists of five quarries, with the posted coordinates being located within the largest of these.

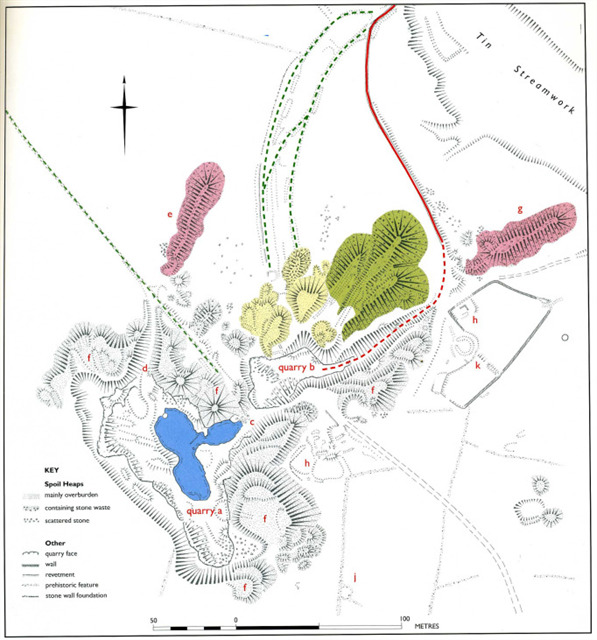

Plan of the quarry

[Key to the plan: (quarry a) and (quarry b) are the two working areas, with (quarry a) being the larger and earlier one of the two. (c) is the original entrance to (quarry a) and through this ran a tramway, since removed for reuse elsewhere, and this carried waste material to the spoil heaps highlighted in green. (d) is the second, possibly later, entrance that another tramway ran through and carried the waste material to a single spoil heap (e), which is where stage 1 is located. (f), which marks multiple points on the plan, are spoil heaps of overburden, consisting largely of the overlying Tor Granite or moorstone. (g) is a single spoil heap used for waste material from the later (quarry b). (h) are the two locations of evidence for the ancillary buildings that we know would have been at the site. Although only a small proportion survive today. (j) is the prehistoric remains of a hut circle, and associated section of reaves, indicating that this area was inhabited long before the opening of the quarries. (k) is a circular earthwork, thought to be a 20th century artillery or motor emplacement. The known alignment of the tramways are in green and red. The dashed part of the line indicate parts that no longer have the track way, where as the solid lines are surviving. The green route shows the earlier phases of track, and the red shows the phase seen today.]

Tramway and Spoilheap

The main method of extracting granite from the rock face was to drill lines of deep vertical holes into the natural vertical joints of the rock (see Pil Tor) which were then packed with gunpowder to cause just enough of an explosion to separate large sections of the face without damaging it. After this the granite was further 'cut' using hand tools, most commonly a feather and tare, which leaves tell tale marks on the edges of the rock. The large spoil heaps here show that the process of quarrying granite was a very wasteful process, with a lot of the stone either being damaged or not up to standard. The spoil heaps found at Haytor are classic 'finger dumps' which are called that because from the air they resemble fingers.

Although the story of Haytor quarries is largely one of human industry, the raw resource that they were extracting, granite, was formed between 272 and 308 million years ago. Granite is formed from felsic magma, which is rich in silica. When this magma cools, it forms rock rich in feldspar and quartz. The size of these crystals, which are visible to the naked eye, is due to the magma cooling down, and solidifying, before reaching the surface. This process of cooling results in relatively slow cooling, allowing large crystals to form. Normally the resulting granite is upwards of 80% feldspar and quartz. These feldspar crystals and quartz make up the white, or see through, component of the granite and are easily identifiable. Another common component, and easily identifiable, is mica or biotite mica. This is the darker material, almost black, between the lighter crystal. A common feature, that is found across much of the Dartmoor granite, including the tors, are phenocrysts. These are defined as being conspicuous crystals distinctly larger than the surrounding components of rock.

Granite is actually a term used to describe a range of rocks that have similar composition, and as a result they can range significantly. Two common ways they vary in appearance is the colour, including grey and pink, or the size of the crystals. This variation is the main reason why certain types of granite are used for different purposes. For instance, where appearance isn't a determining factor, then quarrying into a layer of more attractive granite would be a waste of resources. But when contracts, such as those that the quarries around Haytor were opened for, require granite of specific appearance and composition, the increase challenges of extraction area considered reasonable. The geological complexity of Dartmoor makes it a great example for showing the variations that naturally occur within rocks of the same type.

Across Dartmoor there are a wide range of different classifications of granite, with some key differences in their composition, and therefore appearance. The following types are the two types you will see when doing this EarthCache. The most common is either 'moorstone' or 'Tor Granite'. As the latter name suggests this type of granite is commonly found in the tors, as well as many of the granite boulders found littered across much of the Moor. These granite boulders are where it gets the historic 'moorstone' name from. Before people knew, or understood, that the rock abundantly found on Dartmoor was granite, it was referred to as 'moorstone'. If you read any historic texts that claim that buildings or walls were made out of 'moorstone' then you can surmise that they were in fact made from Tor Granite. Tor Granite tends to have relatively large feldspar and quartz crystals, and has high concentrations of phenocrysts. Despite this type of granite being the most common, both in local building material and availability for extraction, it wasn't common exploited for commercial building material, due to its appearance. Instead when a quarry was opened, the overburdening rock, commonly this Tor Granite, was removed and placed onto the spoil heaps, which is what has happened at Haytor. Underneath this granite is the 'Quarry Granite', which the quarrying activities were after. It differs significantly from the Tor Granite, which will be clear when you get to GZ and look around at the rock faces.

Granite with phenocrysts

To log this EarthCache go to the posted coordinates and waypoints and send me a message or email answering these following questions. To answer the first part of this EarthCache you must either have a good idea of what 'typical' granite looks like, and its components, or visit a location to do so before heading to the posted coordinates. I would suggest Haytor itself as being a safe option, but I won't put a waypoint because there are plenty of scattered boulders in between any parking and the posted coordinates that are of the same type of granite.

Go to the posted coordinates and find the platform of granite overlooking the water.

1) Look at the granite and can you identify any 'typical' component of granite that is not present in this 'Quarry Granite'?

2) From your position you should be able to see some remnants of the quarry equipment. Describe them and what do you think they are? (Specific names are not required)

Go to stage 1

3) What feature of the quarry can be seen here?

4) Either estimating or using the provided waypoint, what is the approximate length of the feature?

Go to stage 2

5) What feature of the quarry can be seen here, and describe what they were used for?