THE CACHE

Since I arrived to Sydney I've been thinking that such an iconic landmark was well worth of it's own cache. Due to the high security measures of the site is really difficult to hide anything big around the premises, so this little cache is just the most humble tribute that this architectural masterpiece can get. I know that the site will be muggle central, but the location and the accurate coordinates will give you a quite stealthy search.

It is a magnetic cache, so if you find it just laying on the floor, please reattach it to the top. Happy hunting and please sit and enjoy the views of this architectural gem.

“It stands by itself as one of the indisputable masterpieces of human creativity, not only in the 20th century but in the history of humankind.” Expert evaluation report to the UNESCO World Heritage Committee, 2007.

HISTORY OF THE PLACE

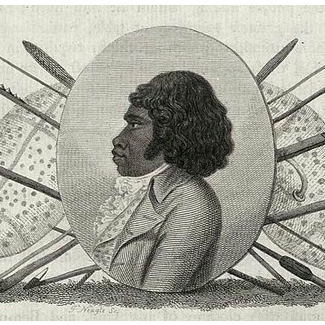

The land on which the Sydney Opera House stands today was known to its traditional custodians, the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation, as Tubowgule, meaning "where the knowledge waters meet." A stream carried fresh water down from what is now Pitt Street to the cove near Tubowgule, a rock promontory that at high tide became an island. The mixing of fresh and salt waters formed a perfect fishing ground. Middens of shells were a testament to Tubowgule's long history as a place where the Gadigal gathered, feasted, sung, danced and told stories.

Tubowgule’s current name of Bennelong Point honours Woollarawarre Bennelong, a senior Eora man at the time of the arrival of British colonisers in Australia in 1788. Kidnapped by the first Governor of New South Wales, Arthur Phillip, Bennelong served as an interlocutor between the Eora and the British. At his request, Governor Phillip built him a hut on the point that now bears his name. Bennelong later became the first Aboriginal Australia to travel to London. In 1871 a fort was built upon Bennelong Point, Fort Macquarie which was completed in 1821. In 1881 Fort Macquarie was also demolished and replaced by a militaristic tram shed.

The idea for a dedicated performing arts centre in Sydney had been discussed for decades, yet it was not until the mid-1950s that it gained enough political traction to become a reality. A key advocate for a new opera house was English composer Sir Eugene Goossens, who moved to Sydney in 1947 to take up the position of conductor of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra. Sir Eugene had spent the previous 20 years as the conductor of orchestras in the United States that performed in large, purpose-built halls. The Sydney Symphony Orchestra, in contrast, performed in the 1889 Sydney Town Hall. Upon his arrival in Sydney, Goossens immediately drew attention to the inadequate facilities.

Another key advocate was Joseph Cahill, a railway worker who entered politics and became NSW Premier in 1952. A former Minister for Public Works, Cahill shared Sir Eugene’s belief that all people, regardless of their class or background, had the right to enjoy fine music. Soon after he became Premier, Cahill promised an opera house for Sydney and in 1954 convened a conference to build support for the idea.

The following year, in 1955, Bennelong Point was declared the site for the proposed new opera house and on 15 February, 1956 Premier Cahill released an international competition for “a National Opera House at Bennelong Point.”

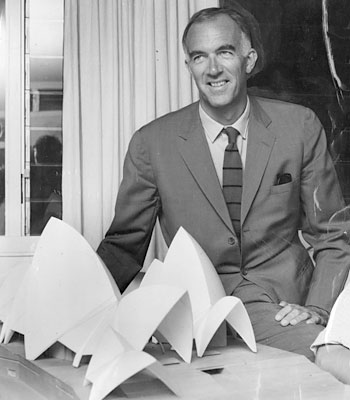

On 9 April 1956, Danish architect Jørn Utzon celebrated his 38th birthday and set to work in his modest office in Hellenbaek, north of Copenhagen, on his designs for the competition. He sent his 12 drawings to Sydney just before the competition closed in December.

Judging began a few weeks later in January 1957. Jørn Utzon’s design was numbered 218 – one of the last of more than 223 entries received from 28 countries.

Four men were selected to judge the entries and there is no precise record of how the winning design was chosen. A widely-told story is that Saarinen, who had missed the beginning of the ten days set aside for judging, was underwhelmed by the already shortlisted entrants and pulled Utzon’s entry out of a pile of rejected schemes, exclaiming that it was easily the winning design.

By the mid-1950s, modernism and the International Style of architecture had been in the ascendancy for 30 years. Rejecting the decorative motifs and ornamentalism of pre-WWI architecture, modernist architects preferred to reveal a building’s structure, emphasising function over form. Such modernist buildings typically resembled glass boxes, as did many of the entrants to the Sydney Opera House competition.

In contrast, Utzon’s design was more sculptural and embraced expressionism. Among the competition entries, it was singular in making full use of Bennelong Point’s harbour-side setting, which would allow the building to be viewed from every angle.

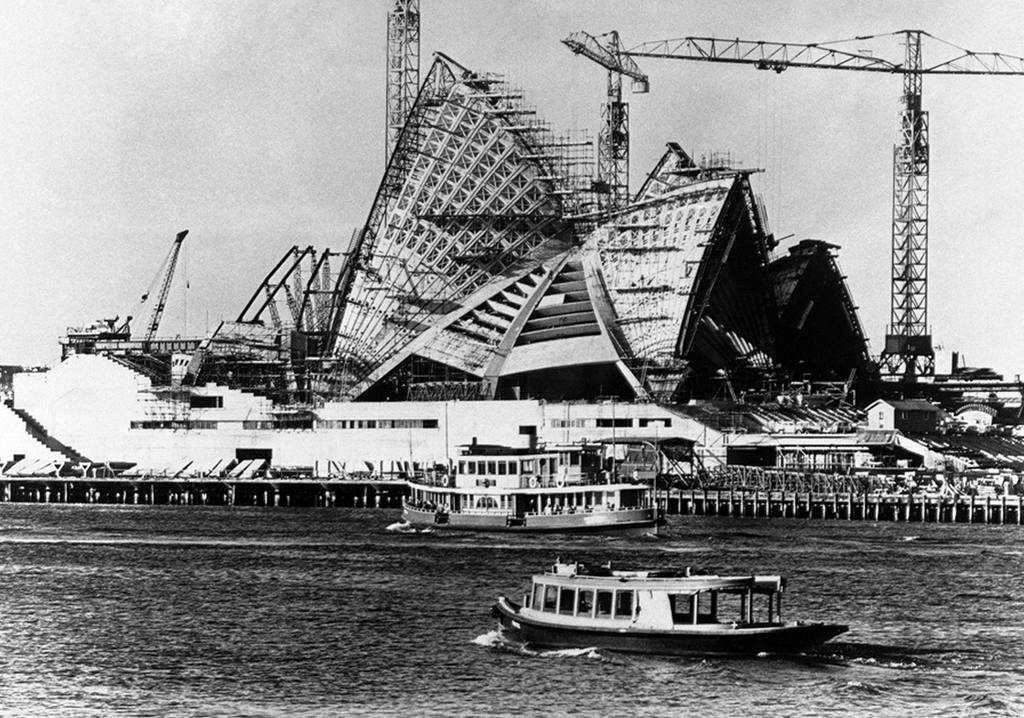

The construction plan was divided on three phases, even nobody knew how to fully finish the building, and no engineer was consulted to check if the roofs were actually being able to be buit. On 2 March 1959, a crowd gathered under umbrellas, in the rain, to watch the ceremony that marked the start of construction of the Sydney Opera House.

Two major problems confronted the engineers in their approach to Stage One. First, the geology of Bennelong Point had not been surveyed accurately at the time of the competition guidelines, and the second major problem related to the as yet unknown weight of the roof, which would change dramatically in the coming years. The anchor points of the roof were at this stage only vaguely discernible; the load they would have to bear was unknown. A more prudent plan would have been to solve the design problems before commencing construction. But Premier Cahill was in a hurry, fearful the project would get stymied by bureaucracy or political opposition.

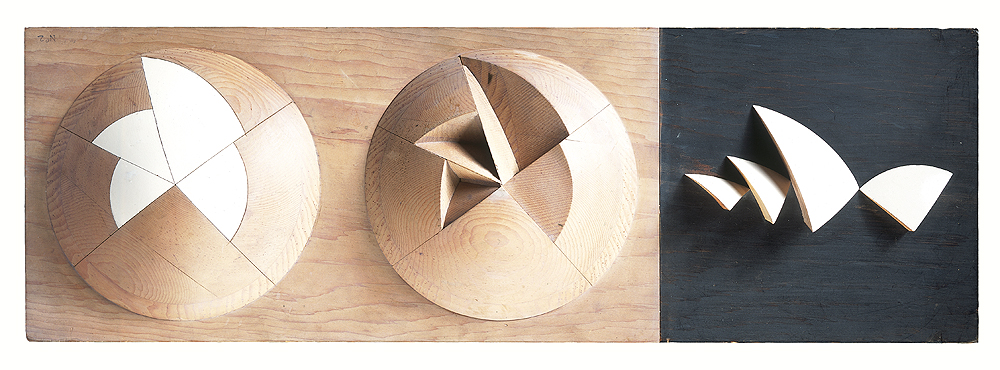

As construction of the podium began in Sydney, Jørn Utzon and his team of architects back in Hallebaek explored how to build the Opera House’s shell-shaped roof. Between 1958 and 1962, the roof design for the Sydney Opera House evolved through various iterations as Utzon and his team pursued parabolic, ellipsoid and finally spherical geometry to derive the final form of the shells. The eventual realisation that the form of the Sydney Opera House's shells could be derived from the surface of a sphere marked a milestone in 20th century architecture.

Various myths surround the discovery of the so-called Spherical Solution, the unified answer to the problems of buildable shells. The iconic sculptural form of the Sydney Opera House essentially relies on the form of these shells, so the importance of finding the best solution to the roof cannot be underestimated.

As one of the more popular myths has it, Utzon had a eureka moment while peeling an orange.

Utzon was stacking the shells of the large model to make space when he noticed how similar the shapes appeared to be. Previously, each shell had seemed distinct from the others. But now it struck him that as they were so similar, each could perhaps be derived from a single, constant form, such as the plane of a sphere.The simplicity and ease of repetition was immediately appealing.

It would mean that the building's form could be prefabricated from a repetitive geometry. Not only that, but a uniform pattern could also be achieved for tiling the exterior surface. It would become the single, unifying discovery that allowed for the distinctive characteristics of Sydney Opera House to be finally realised, from the vaulted arches and timeless, sail-like silhouette of the Opera House to the exceptionally beautiful finish of the tiles.

Utzon wanted the shells to contrast with the deep blue of Sydney Harbour and the clear blue of the Australian sky. The tiles needed to be gloss but not be so mirror-like to cause glare. Three years of work by Höganäs of Sweden produced the effect Utzon wanted in what became known as the Sydney Tile.

The 4228 tile chevrons required to cover the shells were produced in a factory set up under the Monumental Steps. In total, there are 1,056,006 tiles on the roof. American architect Louis Kahn would make the most enduring comment about the luminous effect of the tiles: “The sun did not know how beautiful its light was, until it was reflected off this building.”

With the riddle of how to build the shells now solved, Stage Two and the construction of the roof began in 1963. This phase took three years, but as the building came together, relations between Utzon and the NSW Government fell apart. There was a political change and there was no more support from Joseph Cahill. The new politicians grew concerned about the building’s mounting costs and some sought to turn the problems to their own political advantage. Utzon maintained his insistence on maintaining complete control over his building so as to ensure his vision would be achieved. As the vaulted sails took shape, Bennelong Point became a battle ground of politics, pragmatism and the quest for perfection. Ultimately one of these was to yield to the others.

Stimated at just 3 years time and a 7 million budget, the project was finished in 14 years and an oustanding 102 millions in costs... But way before reaching these figures, the tensions were so high, they even stoped paying the firm, that by 1966 Utzon was forced to resign, never to come back or seein with his own eyes his masterpiece finished.

Matters began to turn against Utzon in 1962. His Spherical Solution for the roof had been approved but the cost of the building – estimated at just 3.5 million pounds when construction began in 1959 – was increasing. By the middle of 1962, the estimated cost had hit 13.7 million pounds. Norman Ryan, the Minister for Public Works, to whom Joseph Cahill had entrusted the Opera House from his death bed, stepped up supervision of Utzon. Instructions by the government in 1963 to change the seating arrangements in the main hall increased the pressure on the architect and tensions grew between the architect and his engineers.

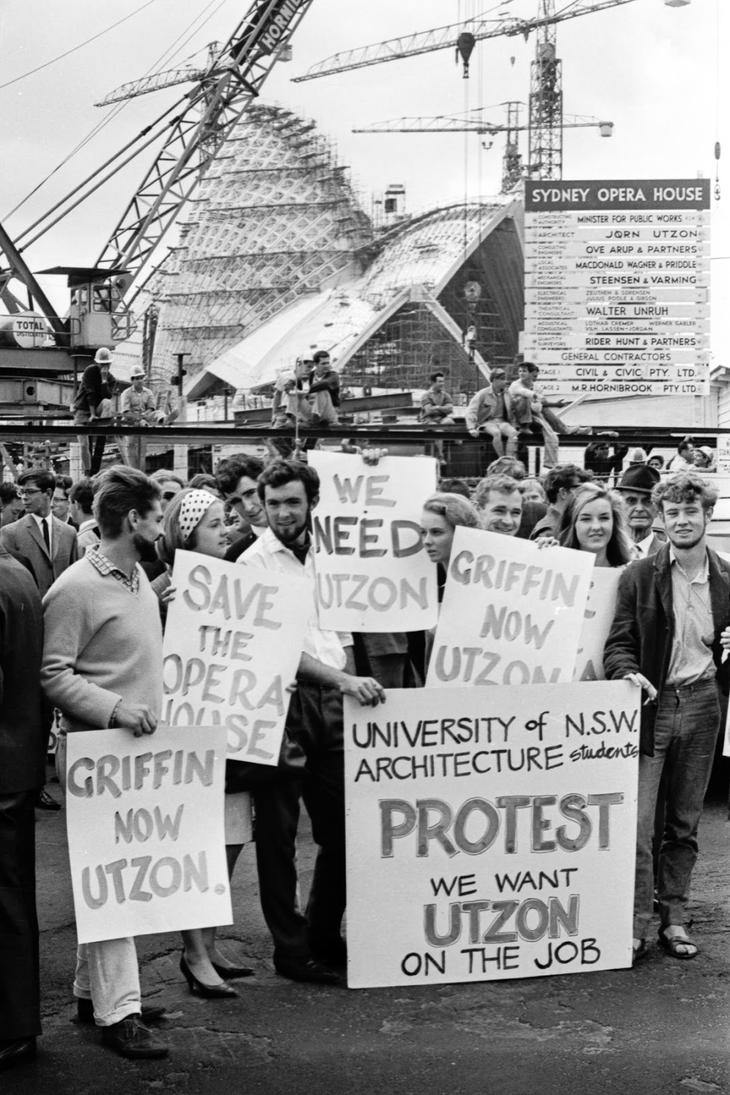

Utzon’s resignation caused an unprecedented outcry. There were letters of protest from eminent artists, designers and intellectuals from across the globe. On 3 March, 1000 people marched on State Parliament through the streets of Sydney led by architect Harry Seidler, author Patrick White and others, who demanded that Utzon be reinstated. A further rally organised by a group that called itself ‘Utzon-in-Charge’ was held and a petition of 3000 signatures was delivered to Premier Askin. The building was left untouched for the next two years, with just the shells completed, and many mentioned that it should have been left this way.

On 19 April 1966 Davis Hughes appointed a new panel of Australian architects to complete the Opera House: Peter Hall would be in charge of design. Peter Hall was one of Australia's brightest young architects at the time he took up the daunting role of design, interpretate and complete Stage Three, the interiors of Sydney’s new Opera House. Instead of the documentation they were expecting to find, all that Utzon had left were sketches and designs.

Finally australian culture reached a remarkable milestone on 20 October 1973: the completion of one of the greatest buildings of the 20th century, the birth of an icon, and the beginning of an incredible performance history at Sydney’s new Opera House.

“The Sydney Opera House has captured the imagination of the world, though I understand that its construction has not been totally without problems,” Queen Elizabeth II observed, officially opening Jørn Utzon’s masterpiece on a blustery spring day. But as the Queen went on to say: “The human spirit must sometimes take wings or sails, and create something that is not just utilitarian or commonplace.”

The Queen’s words could not have been more appropriate to the occasion. It was a day that brought to a conclusion the saga of the building’s conception, design and construction, a saga in which controversies and politics upended what had seemed for many years as idealistic a quest for architectural perfection as had been seen in the post-war world.

Some had feared that the Sydney Opera House might never be finished. To others, its perfection was forever compromised by the manner of its completion.

But his story need a much happier ending, as in 1999 Jørn Utzon re-engaged the project in order to design the architectural principles guide, with his son returning to the site to complete the vision of his father. Utzon expent his last 9 years commited again to his project seeing the recognition he much deserved happening: winning the Pritzker prize in 2003 and seeing his masterpiece being included in the UNESCO Heritage site in 2007, just one year before his death.

Many people still asked him if he never felt sad of not have being able to see his masterpiece finish, but simply he responded:

Sydney Opera House was not just a project for me, it is a proof of my love and commintment. I know the project as the palm of my hand, and I don't need to be back in Sydney to see it with my own eyes, as I can picture my building everyday in my mind.