This simple EarthCache is located within Queen Elizabeth Country Park (‘QECP’), for which the Park Authorities are gratefully thanked for their kind permission to site this EarthCache within QECP.

QECP is a large 6 km² country park situated on the South Downs, a few miles from Petersfield, and forms part of the East Hampshire Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, and, since April 2011, part of the South Downs National Park. This EarthCache is sited outside the cafe area of the QECP Visitors Centre, where one can walk on tarmac and paved pathways immediately adjacent to the building, so making this EarthCache perfectly accessible for both strollers and wheelchairs. Further from this area, QECP is criss-crossed by gravel/bare paths (some of which can have quite steep inclines), so wheelchair and stroller access would be more limited, especially in wetter weather. Several of these pathways make up sections of several Long-distance footpaths that run through the park, including ‘Staunton Way’, ‘Hangers Way’ and the ‘South Downs Way bridleway’. The park also has several well regarded, waymarked and graded mountain biking trails if one wishes to explore and cache at a faster pace than on foot.

As usual with EarthCaches there is no physical cache. To log this EarthCache, the cacher is required to study the landscape that one can see from the QECP Visitors Centre, and then email me the answer to the questions below.

QECP comprises 2 main habitats:

- Lofty hills (called ‘Downs’), and

- Wooded valleys, perched between the hills

Lofty Hills (‘Downs’)

The Downs to the west of the Visitor Centre are one of ten geological Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs) within the South Downs National Park.

If the cacher enters QECP from the north, you cannot miss the steep northward-facing escarpment of the scarp slope that defines the northern edge of the South Downs, stretching over 70 miles from Winchester in the west, towards Eastbourne, in the east. Alternatively, if the cacher enters QECP from the south, they will experience a different view, of gently rolling flatter hills that gradually gain in height as you move northwards towards the escarpment.

As one drives, walks, horse-rides, or bikes to the Visitor Centre, one cannot help notice the underlying bedrock of these Downs, exposed in cliff-faces and in the worn footpaths and bridleways. As one stands at the GZ and looks to the west at the flank of the hill slope (and the edge of the ‘Geological SSSI’) in front of you, you will see a mad-made road cutting, in which the underlying bedrock is exposed.

This unique bedrock was formed in a warm shallow sea during the Cretaceous Period. Imagine the scene – you are swimming around the sea, trying to hide from the sharks and bony fish, who themselves are also trying to hide from not only the plesiosaurs and crocodiles, but also the ferocious 14m-long Mosasaurs. The sea-bed is covered with a variety of shells, sea-urchins, worms and snails, all moving in-between the gigantic clam shells and massive corals, with ammonites (some over 1m in diameter!), lazily swimming around you. But you cannot easily see all of the creatures because the sea has a milky-white appearance, due to the billions of microscopic limey-shelled coccoliths, foraminifera, and plankton that float in front of your eyes, being washed around by the sea currents.

Now imagine this sea-bed, maybe also covered with the bones of the half-eaten larger fauna, being covered with a thick layer of dead coccoliths, foraminifera, and plankton. On top of this, over the next few hundred years, a new sea-bed community appears and then thrives, only to be wiped out again by another blanket of microscopic fauna. Now repeat this for millions of years and you can then understand how this rock was formed.

QUESTION 1 - What colour is the underlying bedrock that you see, and what is it called?

QUESTION 2 – If you had a time machine, would you like to scuba dive in these seas?

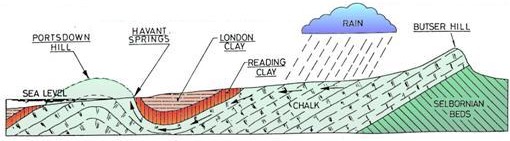

This rock itself was deposited over the older layers of Gault Clay and Upper Greensand, both formed in shallow sea type environments. Deposited on top of the bedrock we see here at QECP (and so are younger) were the Palaeogene-aged clays, silts, sands and gravels, the results of swamps, estuaries and deltas washing in to a marginal coastal plain. Then, over millions of years, as the Alps formed to the south, all of these rocks were then folded and tilted, forming the underlying geological structures that we see today.

Geological Cross-Section from The Solent in the south, to Petersfield in the north

The underlying bedrock here is very porous, and serves as the aquifer that provides the drinking water for this area of southern England. When the rains fall, the ground looks barely wet, as the rainwater soaks straight through the thin soils that cover the higher Downs, percolating downwards into the underlying limestone. The northern edge of the escarpment is punctuated by valleys that cut into the steep hillsides; dry for most of the year (hence their name ‘dry-valleys’), during prolonged spells of heavy rain, the underground water table can rise up so high that it affects the flow of water at the surface, allowing surface streams to form along these valleys.

Wooded Valleys

Around 5000 years ago, the whole of southern England would have been covered in lush deciduous forest. The tree cover of the Downs is believed to have been cleared during the Bronze and Iron Ages (evidence of which can be seen throughout QECP), with humans introducing sheep to the environment, so changing the natural habitat from forest, to the chalky grasslands we know today.

The woodlands you see today at QECP were mostly planted less than 100 years ago, providing mainly beech and conifer trees for many local industries. Fine examples of these can be seen on the valley sides that border the Visitor Centre, the tall trees rising proudly from the leaf litter that covers the areas of woodland floor, within which a variety of fauna lives, including various mammals, birds, reptiles and birds all live. These animals, along with the distinct flora in these sections of QECP help make up the inter-twinned community of the wooded valley slopes and floors; as the organisms die, they are either eaten or decompose, allowing them to eventually become part of the soil, which itself builds up over time to have a more clay-like, non-porous consistency. The latter can be seen in periods of wetter weather, when surface streams can flow along the paths, over the layers of soils and clay-like deposits formed in these localised areas. These streams themselves can transport sediments such as gravels, silts and clays, depositing these in the lower-lying areas, forming patchy ‘Head Deposits’.

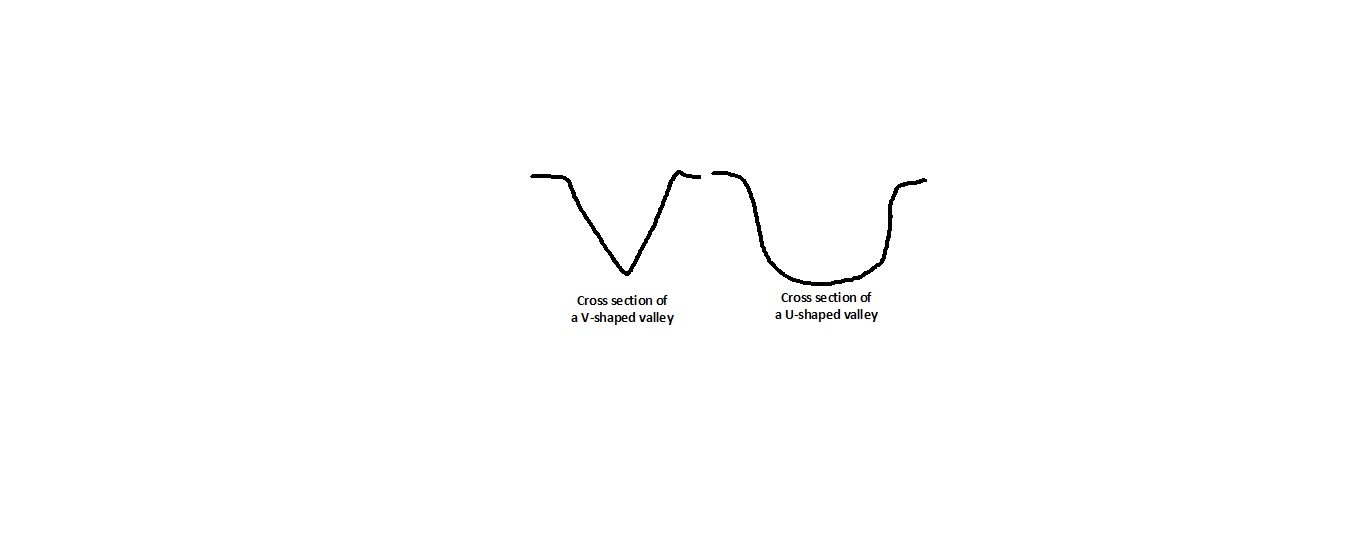

When studying topography (the shape of the landscape), the geologist has to consider both the underlying bedrock, and also processes that either are or were active at the surface. At a basic level, valleys are formed due to the effect of flowing water, whether this be frozen (i.e. ice , as a glacier) , or liquid (as a stream or river). The former creates a ‘U-shaped’ valley cross section, the latter a ‘V-shaped’ valley cross section.

The Different Cross-Sectional Views of a ‘V-shaped’ and ‘U-shaped’ valley

As you stand at the GZ, work out the cross-sectional shape of the valley: look both north (pretend the building is not there!) and southward and note the shape of the valley floor. Now look westward (remember the man-made road-cutting), and then eastward, up the forested valley side.

QUESTION 3 – Was this valley carved by flowing ice (i.e. a glacier), or by flowing liquid water (i.e. a stream or river), and how can you tell?

As you can see, this valley is now very ‘dry’, but immediately to the south of the Visitors Centre is a pond!

QUESTION 4 – How do you explain this large pond, when the bedrock geology here is a porous limestone?

Once you have completed the above observations, please turn around and head towards the door into the café. As you approach the door, you cannot miss the old ‘milestone’.

QUESTION 5 – When originally sited not far from here, how far away was London from the Milestone?

This EarthCache has explained a lot about sedimentary rocks. This is one main type of rock – the other rocks types are igneous and metamorphic.Igneous rocks are formed by molten magma cooling and crystallising, giving a crystalline structure of randomly-orientated interlocking crystals. Metamorphic rocks form by older rocks being subjected to temperature and/or pressure, giving a crystalline structure of flat, planar crystals all being aligned in one general direction.

QUESTION 6 – What rock do you think the milestone was carved from, and what deductions helped you reach this answer?

.

Once you have all the information for the above questions, please email me the answers before logging your visit. I endeavour to respond ASAP, however if I have not within 48 hours, please do email me again.

Please do post photos of the yourself and/or the numerous stunning views you will experience in this magnificent country park.

Good luck!