For more information on floating the river and the first EarthCache in this series, please see this link.

For the next EarthCache in the trail, click here.

-------------------------------

Leaving a Trace – Fossils in the Breaks

As you continue up the coulee, the walls narrow, and at some point your GPS accuracy may get spotty, or lose its satellite connection all together. If that happens, don’t worry. You can’t really get lost in a slot canyon, and the location of the next EarthCache is easy to describe the old fashioned way: it is on a rock face on the left side of the coulee beneath an overhang, near a clump of boulders. The GPS coordinates should still direct you to the general area. The site is about 25 feet before a fork in the coulee. If you hit the fork, you know you’ve gone too far.

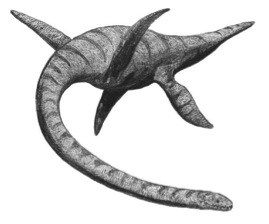

If you recall from the first EarthCache, around 100 to 65 million years ago, a narrow ocean corridor called the Western Interior Seaway once divided North America into two separate landmasses. This inland sea was a favorite habitat for marine creatures. Large reptiles, now extinct, such as mosasaurs and long-necked plesiosaurs swam the waters. Giant ancient crocodiles called deinosuchus, which grew up to 12m long (that’s 39 feet!), lived on both sides of the Seaway, probably hunting aquatic and terrestrial prey. On land, herds of duck-billed and horned dinosaurs migrated across the surrounding plains.

Artist’s reconstruction of a plesiosaur, by Adam Stuart Smith (Wikipedia Commons)

Artist’s reconstruction of a plesiosaur, by Adam Stuart Smith (Wikipedia Commons)

Although these enormous and awe-inspiring reptiles and dinosaurs usually draw most of our attention, invertebrates (animals without a backbone) also flourished in this time period. One such invertebrate was ophiomorpha, a worm-like creature that lived on the floor of the Western Interior Seaway. As layers of sediment accumulated on the sea bottom, sometimes, under favorable conditions, traces or remains of these creatures were preserved in the sedimentary rock.

The odd, dark markings on the rock face before you are an example of this. These markings are actually a type of fossil: ancient burrows dug by ophiomorpha, which have since been filled in by material and preserved. The burrows are an example of bioturbation, the disturbance or reworking of sedimentary deposits by living organisms. Some sedimentary deposits can be so heavily bioturbated that the bedding is obscured and the rock appears massive (having no discernable pattern or structure).

Bioturbation can obscure or even destroy bedding in sedimentary rock (Photo by Robert Boessenecker)

Bioturbation can obscure or even destroy bedding in sedimentary rock (Photo by Robert Boessenecker)

A fossil is defined as any recognizable trace of ancient life that has been preserved in sedimentary rock by natural processes. There are two main types of fossils: 1) Body fossils, which are what most people think of when they think of a fossil—preserved bones or hard body parts, such as the shell of a clam; and 2) Trace fossils or ichnofossils, which are evidence of organism activity such as trails, footprints, or burrows.

In order for a fossil to be preserved, it must be buried quickly so it does not decompose on the surface. There are several different mechanisms of fossil preservation. Seldom is the original material preserved (this happens in very rare cases, such as insects being encased in amber from tree sap, or more recent animals being frozen in ice). Instead, processes such as mineral replacement or permineralization usually preserve body fossils.

As the name indicates, in mineral replacement, minerals dissolved in solution precipitate and replace organic material. This is the process that creates petrified wood. When silica-rich groundwater passes through a log, it replaces the organic plant structure with inorganic stone, and the inner structure of the tree is preserved.

In contrast, permineralization involves minerals in solution filling the void spaces of a fossil, but not actually replacing the original material.

Natural molds and casts are also possible. It is easy to confuse the two: molds form when a fossil decays or dissolves in sediment, leaving a cavity in the rock. If this cavity is consequently filled by sediment or minerals precipitated from solution, a cast is created.

Trilobite mold (top) and cast (bottom)

Photos by R.Weller, Cochise College and the Exhibit Museum of Natural History

Trilobite mold (top) and cast (bottom)

Photos by R.Weller, Cochise College and the Exhibit Museum of Natural History

Impressions are another type of fossil. They reflect the settling of objects or organisms on soft sediment in deep lake or marsh environments, required to preserve the fossil. Leaf impressions are a common example of this type of fossil.

Leaf impression from Fort Union Formation in Big Horn County, Montana

Source: Viney, M. (2008). The Virtual Petrified Wood Museum, http://petrifiedwoodmuseum.org

Leaf impression from Fort Union Formation in Big Horn County, Montana

Source: Viney, M. (2008). The Virtual Petrified Wood Museum, http://petrifiedwoodmuseum.org

Fossils are important, not only because they inform us about prehistoric life on Earth, but also because they inform us about time on Earth. As early geologists and paleontologists began to uncover fossils, they noticed that fossils were not randomly distributed, but that certain fossils were confined to specific beds. In the early 1800s, geologists realized that the planet’s rocks could be organized temporally, since some species were limited to a particular period in time because they were wiped out by large-scale extinction events. Eventually, these early geologists began to formalize a geologic timescale, with certain time periods identified by characteristic fossils, now called index fossils. Geologists concluded that even when two rock layers are distant geographically and differ compositionally, if they contain the same fossil then they must have been laid down in the same time period when that species was alive. Organisms that make good index fossils: 1) Have widespread geographic distribution, 2) Are easily identifiable, 3) Are robust and easily preserved, and 4) Belong to a relatively short-lived species, which allows for precise correlation in the rock record. The practice of using fossils to correlate and date strata is called biostratigraphy. It is arguably the most useful tool for subdividing and organizing the rock record easily and quickly, without having to resort to complex and expensive radiometric dating methods.

Some other index fossils commonly found in the Missouri Breaks include baculites and ammonites. If you find any fossils on your own, please do not remove them. You are in a National Monument, so you need a BLM permit to collect them.

Ammonite (curly-shelled) and baculite (straight-shelled) reconstruction at the Black Hills Institute of Geological Research. Source: Wooster Geologists, http://woostergeologists.scotblogs.wooster.edu/2011/11/

Ammonite (curly-shelled) and baculite (straight-shelled) reconstruction at the Black Hills Institute of Geological Research. Source: Wooster Geologists, http://woostergeologists.scotblogs.wooster.edu/2011/11/

Ammonite fossil, top, and baculite fossils, bottom, with characteristic suture pattern

Sources: Public Domain and the Wikipedia Commons

Ammonite fossil, top, and baculite fossils, bottom, with characteristic suture pattern

Sources: Public Domain and the Wikipedia Commons

To claim this cache: Answer the following questions and send the answers using Geocache's messaging tool.

Q. What kind of fossil is located at this site? Describe the main type of fossil and try and specify the method of preservation.

Q. What is the length of the longest fossil at this site? If you don’t have a ruler, size it up it with a piece of paper or book and then measure that object later when you have access to a ruler.

Onward! After you have found this EarthCache, feel free to continue on to the fork in the coulee. Turn right and you will enter an incredible slot canyon. Eventually you will come across a boulder that appears to be blocking your path, but there is a small hole underneath it that you can wriggle through. Beyond the boulder, follow the slot canyon until it opens up. You can turn around and retrace your steps, or scramble up the sandstone to your left and eventually drop into the other fork of the coulee that you passed before, which you can follow back out. After you leave the coulee, consider re-calibrating your GPS, which may be off due to interference from the narrow canyon walls.

BONUS QUESTION: Q. What feature is located in the sloped sandstone rock at N 47º54.318, W 110º02.632? (Hint: see EarthCache #8)