Metamorphic rocks

Metamorphic rocks arise from the transformation of existing rock types, in a process called metamorphism, which means "change in form".The original rock (protolith) is subjected to heat (temperatures greater than 150 to 200 °C) and pressure (150 megapascals (1,500 bar) causing profound physical or chemical change. The protolith may be a sedimentary, igneous, or existing metamorphic rock.

Metamorphic rocks make up a large part of the Earth's crust and form 12% of the Earth's land surface.They are classified by texture and by chemical and mineral assemblage (metamorphic facies). They may be formed simply by being deep beneath the Earth's surface, subjected to high temperatures and the great pressure of the rock layers above it. They can form from tectonic processes such as continental collisions, which cause horizontal pressure, friction and distortion. They are also formed when rock is heated by the intrusion of hot molten rock called magma from the Earth's interior. The study of metamorphic rocks (now exposed at the Earth's surface following erosion and uplift) provides information about the temperatures and pressures that occur at great depths within the Earth's crust. Some examples of metamorphic rocks are gneiss, slate, marble, schist, and quartzite.

|

|

|

|

|

| gneiss |

slate |

marble |

schist |

quartzite |

The layering within metamorphic rocks is called foliation (derived from the Latin word folia, meaning "leaves"), and it occurs when a rock is being shortened along one axis during recrystallization. This causes the platy or elongated crystals of minerals, such as mica and chlorite, to become rotated such that their long axes are perpendicular to the orientation of shortening. This results in a banded, or foliated rock, with the bands showing the colors of the minerals that formed them.

Textures are separated into foliated and non-foliated categories. Foliated rock is a product of differential stress that deforms the rock in one plane, sometimes creating a plane of cleavage. For example, slate is a foliated metamorphic rock, originating from shale. Non-foliated rock does not have planar patterns of strain.

Rocks that were subjected to uniform pressure from all sides, or those that lack minerals with distinctive growth habits, will not be foliated. Where a rock has been subject to differential stress, the type of foliation that develops depends on the metamorphic grade. For instance, starting with a mudstone, the following sequence develops with increasing temperature: slate is a very fine-grained, foliated metamorphic rock, characteristic of very low grade metamorphism, while phyllite is fine-grained and found in areas of low grade metamorphism, schist is medium to coarse-grained and found in areas of medium grade metamorphism, and gneiss coarse to very coarse-grained, found in areas of high-grade metamorphism. Marble is generally not foliated, which allows its use as a material for sculpture and architecture.

Another important mechanism of metamorphism is that of chemical reactions that occur between minerals without them melting. In the process atoms are exchanged between the minerals, and thus new minerals are formed. Many complex high-temperature reactions may take place, and each mineral assemblage produced provides us with a clue as to the temperatures and pressures at the time of metamorphism.

Metasomatism is the drastic change in the bulk chemical composition of a rock that often occurs during the processes of metamorphism. It is due to the introduction of chemicals from other surrounding rocks. Water may transport these chemicals rapidly over great distances. Because of the role played by water, metamorphic rocks generally contain many elements absent from the original rock, and lack some that originally were present. Still, the introduction of new chemicals is not necessary for recrystallization to occur.

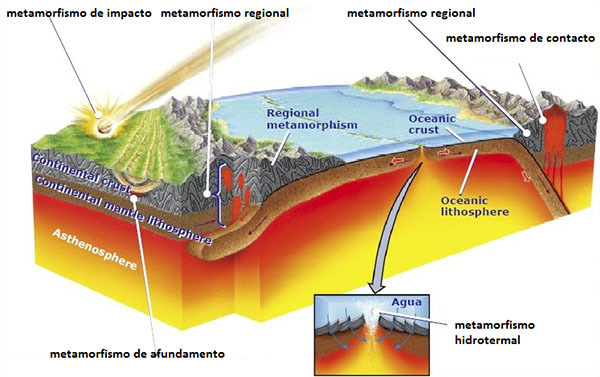

Types of metamorphism

Contact metamorphism

Contact metamorphism is the name given to the changes that take place when magma is injected into the surrounding solid rock (country rock). The changes that occur are greatest wherever the magma comes into contact with the rock because the temperatures are highest at this boundary and decrease with distance from it. Around the igneous rock that forms from the cooling magma is a metamorphosed zone called a contact metamorphism aureole. Aureoles may show all degrees of metamorphism from the contact area to unmetamorphosed (unchanged) country rock some distance away. The formation of important ore minerals may occur by the process of metasomatism at or near the contact zone.

When a rock is contact altered by an igneous intrusion it very frequently becomes more indurated, and more coarsely crystalline. Many altered rocks of this type were formerly called hornstones, and the term hornfels is often used by geologists to signify those fine grained, compact, non-foliated products of contact metamorphism. A shale may become a dark argillaceous hornfels, full of tiny plates of brownish biotite; a marl or impure limestone may change to a grey, yellow or greenish lime-silicate-hornfels or siliceous marble, tough and splintery, with abundant augite, garnet, wollastonite and other minerals in which calcite is an important component. A diabase or andesite may become a diabase hornfels or andesite hornfels with development of new hornblende and biotite and a partial recrystallization of the original feldspar. Chert or flint may become a finely crystalline quartz rock; sandstones lose their clastic structure and are converted into a mosaic of small close-fitting grains of quartz in a metamorphic rock called quartzite.

If the rock was originally banded or foliated (as, for example, a laminated sandstone or a foliated calc-schist) this character may not be obliterated, and a banded hornfels is the product; fossils even may have their shapes preserved, though entirely recrystallized, and in many contact-altered lavas the vesicles are still visible, though their contents have usually entered into new combinations to form minerals that were not originally present. The minute structures, however, disappear, often completely, if the thermal alteration is very profound. Thus small grains of quartz in a shale are lost or blend with the surrounding particles of clay, and the fine ground-mass of lavas is entirely reconstructed.

By recrystallization in this manner peculiar rocks of very distinct types are often produced. Thus shales may pass into cordierite rocks, or may show large crystals of andalusite (and chiastolite), staurolite, garnet, kyanite and sillimanite, all derived from the aluminous content of the original shale. A considerable amount of mica (both muscovite and biotite) is often simultaneously formed, and the resulting product has a close resemblance to many kinds of schist. Limestones, if pure, are often turned into coarsely crystalline marbles; but if there was an admixture of clay or sand in the original rock such minerals as garnet, epidote, idocrase, wollastonite, will be present. Sandstones when greatly heated may change into coarse quartzites composed of large clear grains of quartz. These more intense stages of alteration are not so commonly seen in igneous rocks, because their minerals, being formed at high temperatures, are not so easily transformed or recrystallized.

In a few cases rocks are fused and in the dark glassy product minute crystals of spinel, sillimanite and cordierite may separate out. Shales are occasionally thus altered by basalt dikes, and feldspathic sandstones may be completely vitrified. Similar changes may be induced in shales by the burning of coal seams or even by an ordinary furnace.

There is also a tendency for metasomatism between the igneous magma and sedimentary country rock, whereby the chemicals in each are exchanged or introduced into the other. Granites may absorb fragments of shale or pieces of basalt. In that case, hybrid rocks called skarn arise, which don't have the characteristics of normal igneous or sedimentary rocks. Sometimes an invading granite magma permeates the rocks around, filling their joints and planes of bedding, etc., with threads of quartz and feldspar. This is very exceptional but instances of it are known and it may take place on a large scale.

Regional metamorphism

Regional metamorphism tends to make the rock more indurated and at the same time to give it a foliated, shistose or gneissic texture, consisting of a planar arrangement of the minerals, so that platy or prismatic minerals like mica and hornblende have their longest axes arranged parallel to one another. For that reason many of these rocks split readily in one direction along mica-bearing zones (schists). In gneisses, minerals also tend to be segregated into bands; thus there are seams of quartz and of mica in a mica schist, very thin, but consisting essentially of one mineral. Along the mineral layers composed of soft or fissile minerals the rocks will split most readily, and the freshly split specimens will appear to be faced or coated with this mineral; for example, a piece of mica schist looked at facewise might be supposed to consist entirely of shining scales of mica. On the edge of the specimens, however, the white folia of granular quartz will be visible. In gneisses these alternating folia are sometimes thicker and less regular than in schists, but most importantly less micaceous; they may be lenticular, dying out rapidly. Gneisses also, as a rule, contain more feldspar than schists do, and are tougher and less fissile. Contortion or crumbling of the foliation is by no means uncommon; splitting faces are undulose or puckered. Schistosity and gneissic banding (the two main types of foliation) are formed by directed pressure at elevated temperature, and to interstitial movement, or internal flow arranging the mineral particles while they are crystallizing in that directed pressure field.

Cataclastic Metamorphism

Cataclastic metamorphism occurs as a result of mechanical deformation, like when two bodies of rock slide past one another along a fault zone. Heat is generated by the friction of sliding along such a shear zone, and the rocks tend to be mechanically deformed, being crushed and pulverized, due to the shearing. Cataclastic metamorphism is not very common and is restricted to a narrow zone along which the shearing occurred.

Ground zero is upstairs

Source

Metamorphic rock

Types of metamorphism

|