Der Podsol (aus dem Russischen pod „unter“, zola „Asche“, frei übersetzt „Ascheboden“), auch Bleicherde oder Grauerde genannt, ist ein saurer, an Nährstoffen armer bzw. verarmter Bodentyp in einem feuchtkalten oder feuchtgemäßigten Klima. Die Entstehung von Podsolen bezeichnet man als Podsolierung. Sie bilden sich aus quarzreichen Ausgangsgesteinen wie Sandstein, Granit oder aus lockeren, ebenfalls quarzreichen Sanden, wie z.B. Dünensand. Der geringe Gehalt an verwitterbaren Mineralen führt einerseits zu einem Mangel an Tonmineralen und andererseits zu geringem Puffervermögen gegenüber der Bodenversauerung. Aufgrund des niedrigen pH-Wertes kommt es zu einer abwärts gerichteten Verlagerung (Auswaschung) von Eisen- und Aluminiumhydroxid sowie Huminstoffen mit dem Sickerwasser aus dem Ober- in den Unterboden. Dort werden, bei etwas höheren pH-Werten, die Eisen-, Aluminium- bzw. Humusverbindungen wieder ausgefällt bzw. fixiert. Es entsteht ein ausgeblichener, stark verarmter Oberbodenhorizont (Ae-Horizont) und ein mit Eisenverbindungen und/oder Humus stark angereicherter Unterbodenhorizont (Bs, Bh oder Bsh-Horizont). Die Entwicklung dauert bis zu 1000 Jahre. Der grobporige (wasserdurchlässige) und nährstoffarme Podsol (wenig Humus im Mineralboden) weist aufgrund des niedrigen pH-Wertes ein geringes Bodenleben auf. Dies führt in natürlichem Zustand unter Wald zu einer schwer abbaubaren, mächtigen Rohhumusauflage, die aufgrund ihrer geringen Mineralisierung nur in geringen Mengen pflanzenverfügbare Nährstoffe liefert. Die wasserstauende Ortsteinschicht behindert das Wurzelwachstum. Durch Kalkung und intensive Humuswirtschaft mit Grün- und Stalldüngung kann die Fruchtbarkeit des leicht zu bearbeitenden Podsols deutlich verbessert werden.

Doch wie kam der Podsol in die Haard?

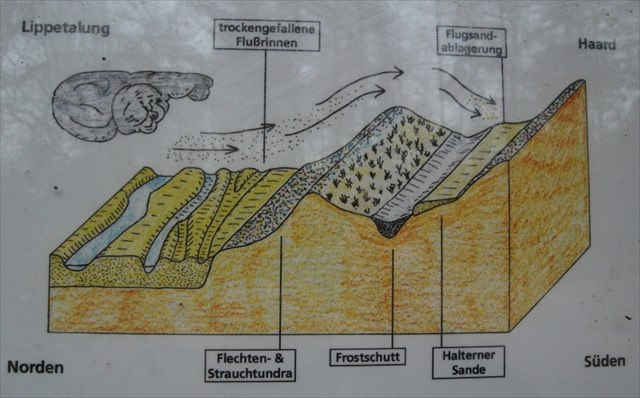

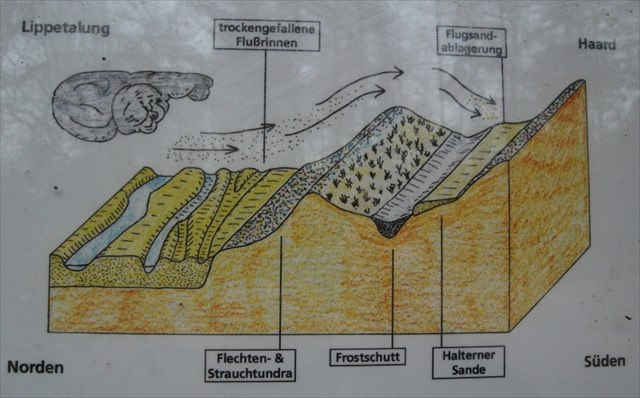

Durch Wind gelangte Sand als sogenannter Flugsand aus dem Lippetal in die Haard und konnte sich im Windschatten der Haardtäler ablagern. Als das Klima und die Vegetation nun begannen sich zu ändern, wurde aus dem Flugsand über mehrere Jahrhunderte bis Jahrtausende hinweg Podsol.

Podsol wurde übrigens am 5. Dezember 2006 durch ein Kuratorium, bestehend aus Mitgliedern der Deutschen Bodenkundlichen Gesellschaft (DBG) und des Bundesverbands Boden (BVB), zum Boden des Jahres 2007 ernannt. Begründet wurde diese Entscheidung damit, dass Podsol eine interessante Entstehungsgeschichte hat, als Archiv für die Nutzung in den vergangenen Jahrhunderten dienen kann und zudem attraktiv aussieht.

Mit dem folgenden Bild könnt ihr den Podsol, der hinter dem Infoschild und neben dem Reitweg zu sehen ist, einordnen:

Quelle des Bildes: fu-berlin

Quellen der Texte Wikipedia, http://www.g-o.de und das Informationsschild vor Ort

Um diesen Cache loggen zu können, beantwortet mir folgende Fragen mit Hilfe der Informationstafel vor Ort:

1. Welchen Durchmesser haben die Körner des Flugsandes?

2. Welche Windstärke reicht aus, damit der Sand durch Wind transportiert werden kann?

3. Welche Dicke hatte die Flugsanddecke, die zum Podsol wurde?

4. Ich würde mich sehr über ein Foto von euch bzw. eurem GPS vor dem Podsol (hinter dem Schild) freuen.

Schickt mir eure Antworten einfach zu und loggt. Sollte etwas nicht korrekt sein, werde ich mich bei euch melden.

In soil science, podzols (also known as podsols or Spodosols) are the typical soils of coniferous, or boreal forests. They are also the typical soils of eucalypt forests and heathlands in southern Australia. The name is Russian for "under ash" (под/pod=under, зола/zola=ash) and likely refers to the common experience of Russian peasants of plowing up an apparent under-layer of ash (leached or E horizon) during first plowing of a virgin soil of this type. These soils are found in areas that are wet and cold (for example in Northern Ontario or Russia) and also in warm areas such as Florida where sandy soils have fluctuating water tables (humic variant of the northern podzol or Humod). An example of a warm-climate podzol is the Myakka fine sand, state soil of Florida.

Most Spodosols are poor soils for agriculture. Some of them are sandy and excessively drained. Others have shallow rooting zones and poor drainage due to subsoil cementation. Well-drained loamy types can be very productive for crops if lime and fertilizer are used.

The E horizon, which is usually 4-8 cm thick, is low in Fe and Al oxides and humus. It is formed under moist, cool and acidic conditions, especially where the parent material, such as granite or sandstone, is rich in quartz. It is found under a layer of organic material in the process of decomposition, which is usually 5-10 cm thick. In the middle, there is often a thin layer of 0.5 to 1 cm. The bleached soil goes over into a red or redbrown horizon called rusty soil. The colour is strongest in the upper part, and change at a depth of 50 to 100 cm progressively to the part of the soil that is mainly not affected by processes; that is the parent material. The soil profiles are designated the letters A (topsoil), E (eluviated soil), B (subsoil) and C (parent material).

The main process in the formation of Spodosols is podzolisation. Podzolisation is a complex process (or number of sub-processes) in which organic material and soluble minerals (commonly iron and aluminium) are leached from the A and E horizons to the B horizon.

In podzols, translocation has meant the eluviation of clays, humic acids, iron, and other soluble constituents from the A and E horizons. These constituents may then accumulate to form a spodic illuvial horizon and in some cases a placic horizon or iron band. Podzolization occurs when severe leaching leaves the upper horizon virtually depleted of all soil constituents except quartz grains. Clay minerals in the A horizon decompose by reaction with humic acids and form soluble salts. The leached material from the A horizon is deposited in the B horizon as a humus-rich horizon band, a hard layer of sesquioxides or a combination of the two. The picture is of a stagnopodzol in upland Wales, and shows the typical sequence of organic topsoil with leached grey-white subsoil with iron-rich horizon below. The example has two weak ironpans.

These sub-processes include mobilisation, eluviation and illuviation. Mobilisation and eluviation both move organic materials and minerals through the A horizon into the B horizon. During this, they react with the water (illuviation) to become oxidised. This process of podzolisation results in the characteristic soil profile of spodosols, in which the E horizon is usually an ashen grey or white colour without structure and there is a distinctive hardpan oxide layer in the B horizon (which is always darker than the E horizon). The E horizon can be dark grey in profiles which are high in organic matter, but in such cases the underlying B is very dark.

However, as conifers allelopathically reduce competition by producing a thick O horizon of mor (acidic and poisonous leaf litter that is slow to decompose), the primary form of plant-soil interactions is that of the conifers themselves. The acidic O horizon, along with rainfall patterns that are similar to that of the moister grasslands, also promotes the illuviation of oxides of aluminium and iron.

In some podzols, the E horizon is absent -- either masked by biological activity or obliterated by disturbance. Podzols with little or no E horizon development are often classified as Brown podzolic soils.

In Western Europe podzols are developed on heathland, which is a construct of human interference, whereby the vegetation is maintained through grazing and burning. The soils may well have developed over the past 3000 years in response to vegetation and climatic changes. In some British moorlands with podzolic soils there are brown earths preserved under Bronze Age barrows.

Spodosols are rare as paleosols. Though they are known from as far back as the Carboniferous, there are few examples surviving from before the first Pleistocene glaciation, and some of these may not be true Spodosols.

But how did the „Podsol“ get into the Haardt?

Because of wind sand from "Lippetal" got as a so called aeolian sand into the "Haardt" and so settled in the shadow zone of the "Haardt valleys". As the climate and the vegetation began to change the aeolian sand became after more than hundred or thousand years „Podsol“.

By the way „Podsol“ was appointed „Ground of the year 2007“ on december 5th, 2006 through a curatorship consisting of members of the „Deutsche Bodenkundliche Gesellschaft (DBG)“ and the „Bundesverband Boden (BVB)“. This decision was justified with „Podsol’s“ interesting evolutionary history, its attractive appearance and that it can be used as a kind of archive of the last centuries.

On the basis of the following picture you can classify „Podsol“ (seen behind the information label and next to the bridleway):

Quelle des Bildes: www.sassa.org

Quellen der Texte Wikipedia und das Informationsschild vor Ort.

To log this cache, please answer the following questions with the help of the local information board:

1. Which diameter do the corns of the aeolian sand have?

("Die Körner der Flugsande haben einen Durchmesser von etwa...")

2. Which storm force is necessary to transport sand through wind?

("Zu ihrem Transport reicht die Windstärke...")

3. Which sickness did the aeolian sand have that became „Podsol“?

("Die Mächtigkeit der über dem Frostschutt gelegenen Flugsanddecke beträgt...")

4. I would be very happy to get a photo of you resp. of your GPS in front of the „Podsol“ (behind the information board).

Send me your answers and log this cache. If something is wrong, I will contact you.