This cave is located down a fairly easy hike from pull out parking

on Ou Kaapse Weg. The parking is easy to see from the road, but

I've given you a waypoint. Remember to not leave any valuables in

your car. It is reasonably safe here, but windows do get smashed

from time to time. At the trail head you will see a sign for Peers'

Cave. The trail is about a kilometer long and is mostly flat, but

does have some boulders on the way. GPS accuracy at GZ is bad, but

you can't miss the spot. You are looking for a large rock shelter,

not a little hidden container. The UCT archaeology department

brings first year students here for a practical. This cache is

partly an adaptation of that assignment. The dificulty rating of

this cache reflects the dificulty of these questions.

This cave is located down a fairly easy hike from pull out parking

on Ou Kaapse Weg. The parking is easy to see from the road, but

I've given you a waypoint. Remember to not leave any valuables in

your car. It is reasonably safe here, but windows do get smashed

from time to time. At the trail head you will see a sign for Peers'

Cave. The trail is about a kilometer long and is mostly flat, but

does have some boulders on the way. GPS accuracy at GZ is bad, but

you can't miss the spot. You are looking for a large rock shelter,

not a little hidden container. The UCT archaeology department

brings first year students here for a practical. This cache is

partly an adaptation of that assignment. The dificulty rating of

this cache reflects the dificulty of these questions.

Today, the cave is named after the local

excavators who dug most of the cave, a father and son team named

Victor and Bertie Peers. It is also known as Skildergat, or

Skildegat. This name may be derived from the rock paintings in the

shelter (Afrikaans Skilerye + gat or painted hole/cave).

Although faint, and often covered by graffiti, these are the only

old rock paintings within 100 km radius of Cape Point. The cave may

also be named after a farm hand named Schilder who used the cave as

shelter for cattle in the 1800s (Schilder's kop).

Geology Lesson: Deposition, Sediment Traps, and

Stratigraphy:

The geology lesson I'd like to teach at this

site is about deposition and stratigraphy. My father asked me a

simple but important question when I first started studying

archaeology. He noticed that archaeologists were always digging

things up. This led him to wonder three related questions:

- Where does all that dirt come from?

- If it keeps burying archaeological sites, does the planet just

keep getting bigger over time?

- Why did people a long time ago spend so much time in caves,

wasn't it nice outside?

I'm going to tell you the answers to two and

three, the answer to question one is what you will need to figure

out. It isn't from meteorites; that was his first guess.

The answer to number two, as any geologist can

tell you, is no; the earth isn't getting bigger. Erosion removes

sediment (dirt) from one place, either by wind or water, and leaves

it behind, deposits it, somewhere else. By this method, dirt moves

from one place to another, exposing some things once buried, and

burying other things once exposed.

The answer to number three is related to this

process as well. Archaeologists dig where we are likely to find

stuff from the past. These places are not necessarily the places

where people hung out the most, but are places where dirt has

accumulated. Places that collect dirt (sediment traps) also bury

evidence from the past. In other words, the reason archaeologists

dig up caves is not because people in the past only hung out

in caves. Rather we like caves, because caves can trap sediment,

and keep it dry and safe.

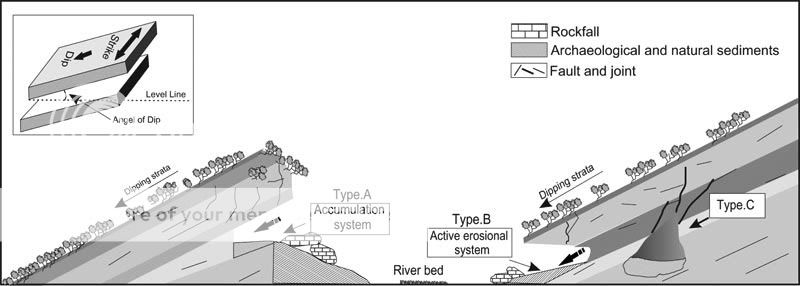

A friend of mine published a paper about why the

area where he works in Iran has caves with deposits on one side of

the valley, and the opposite side of the valley all the caves were

all empty (Heydari, 2007). His explanation was important for

interpreting how people lived in the past. He showed that the

absence of evidence was due to geological causes, and not due the

behaviour of people. I bring it up here because it is helpful for

understanding sediment traps. In many earthcaches you've learned

about bedding planes. Sedimentary rocks (like the Table Mountain

Sandstone here) form in layers. These layers typically are bedded

at an angle (their dip and strike), usually due to movement of the

rocks forming mountains. The following illustration comes directly

from his paper.

Don't worry too much about understanding

everything here. The main thing I want you to get is that because

of the way 'Type A' sites are angled in the bedrock, they collect

sediment like a bucket. Because of the way 'Type B' sites are

angled, they don't collect sediment very well at all, much like a

tipped over bucket. Peers' Cave is more or less a 'Type A' site. A

good example of a nearby 'Type B' site would be

Elephant's Eye Cave. For those of you who've been there, you

know it slopes steeply down and out of the cave. The fact that we

don't have evidence of people living there is not because they

didn't, it is because the shape of the cave didn't allow any

sediment to accumulate, and thereby leave behind evidence. Although

this may seem simple and abundantly obvious, all good science does

once it is pointed out and explained.

Sediment traps, such as caves, are great for

archaeology because there are many different periods of deposition

that create different identifiable layers. Much of how we are able

to know the age of something is due to its position in this

sequence of layers. Understanding the sequence and process of

deposition by looking at these layers is called stratigraphy and is

exactly the same in Geology. In fact, archaeologists stole the

method from geologists. Archaeologists, like geologists,

reconstruct the sequence in which sediment was deposited by looking

at a cross section of layers, called a profile.

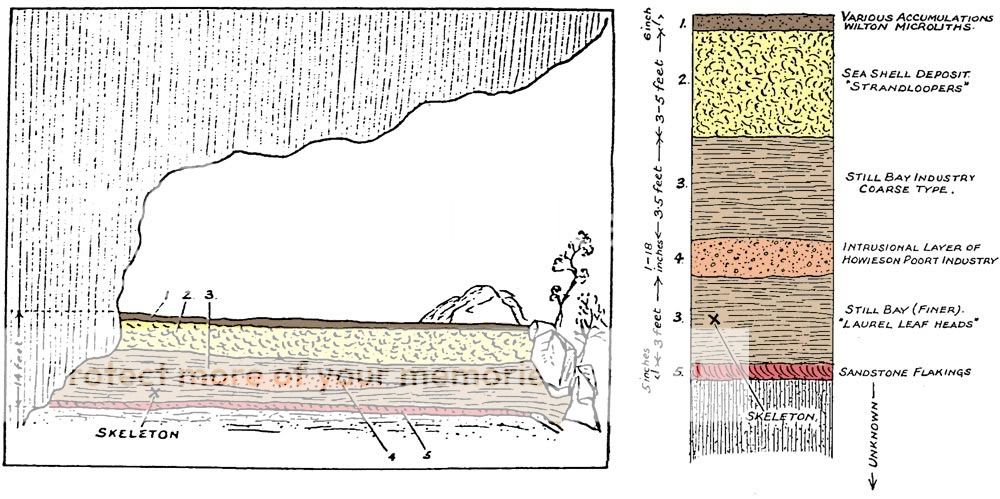

Here is a drawing of the cross-section of the

cave that was published in 1931 (I added colours to make it

clearer). You can see the sediment inside the 'bucket' of the rock

shelter. In the above diagram, layer 3, that contained the

skeleton, must be older than layer 2, because 2 is on top of it. It

must also be younger than layer 5, because 5 is beneath it. This is

called the "Law of

Superposition" which is just a fancy way of saying that the

stuff on top got there later than the stuff under it.

The surface of the sediment in the cave before

it was excavated can be seen on the rock wall when you vist. The

deepest parts were dug over six meters below this original level.

The Peers found nine human skeletons in this shelter. One of them

became famous as the 'Fish Hoek Man', as it came from a layer that

contained very old stone tools. The skeleton (its position is

labeled in the drawing) is often mentioned in histories of the area

as being 12,000 years old. This turns out not to be true, and I

will tell you more below.

The

Peers did not dig in a way that today we would consider to be

careful. They used shovels, picks and dynamite, and as a result,

the layers they identified are very simple. To anyone who has

worked in caves, this is clear from their drawing above; it is way

too simple. Their column represents about 14 feet of depth (just

over 4 meters), and only identifies five layers. There is another

(big) problem with this drawing, but identifying it will be one of

your questions. Sediment traps, such as this rock shelter, create

very complicated series of layers. Once you add people living

there, making fires and digging holes, things get even more

complicated. Understanding these layers, and knowing what came out

of each of them, is what archaeologists (and geologists) do to

understand the past formation of rocks and sediment. On the left is

an example of cave stratigraphy. It comes from the cave site of

Hohle Fels in

Germany. This is what a cross section of a cave should look

like. Really, really complicated.

The

Peers did not dig in a way that today we would consider to be

careful. They used shovels, picks and dynamite, and as a result,

the layers they identified are very simple. To anyone who has

worked in caves, this is clear from their drawing above; it is way

too simple. Their column represents about 14 feet of depth (just

over 4 meters), and only identifies five layers. There is another

(big) problem with this drawing, but identifying it will be one of

your questions. Sediment traps, such as this rock shelter, create

very complicated series of layers. Once you add people living

there, making fires and digging holes, things get even more

complicated. Understanding these layers, and knowing what came out

of each of them, is what archaeologists (and geologists) do to

understand the past formation of rocks and sediment. On the left is

an example of cave stratigraphy. It comes from the cave site of

Hohle Fels in

Germany. This is what a cross section of a cave should look

like. Really, really complicated.

Zambesiboy, in his answers, pointed out another

interesting aspect of sediment traps. They trap the fine sediment

(silt and clay) that gets blown away in other parts of the

landscape. As a result, the soil in shelters is very rich. Or as he

put it: "It actually looks quite good for the garden". Many of the

archaeologically rich caves in South Africa were destroyed by

farmers with this exact thought before there were laws to protect

them. The first of these laws was enacted in 1911, a 100 years ago.

So, please don't go collecting sediment from here, you would not

only destroy valuable information, you'd also be breaking the

law.

Peers' Cave is not a proper cave, but a rock

shelter formed in the Ordovician aged Table Mountain Sandstone that

makes up this rock outcrop. The shelter was formed by the

weathering of less resistant rock along the outcrop, with more

resistant rock above it forming the roof. It faces south across the

Fish Hoek/Noordhoek valley which is covered by shifting sand

dunes.

The sea levels have changed a fair amount in the

past. The last time the valley floor was under water was the late

Miocene or early Pliocene, about 5 million years ago. It was during

this time that a great deal of sand was deposited. Today this sand

forms the dune fields you can see across the valley floor. However,

for most of the time people were living here, sea level was much

lower than it is today, about 40-120 meters lower. This was because

much of the planet's water was in glaciers in the northern

hemisphere. The lowered sea level caused the sea shore to be much

farther away than it is now.

At this point, along with your keen

observational skills, I've given you everything you need to answer

your questions. But first let me tell you a little bit about why

the site is interesting and what was found in the dirt that got

trapped here.

A little information about the archaeology:

This cave contains traces of humans living here

as long ago as 200,000 years ago. Much of the excavation here was

done by the Peers and John Goodwin in 1925-1931. As both the Peers

had full time jobs, work was limited to weekends, public holidays,

and their annual leave. Field Marshal Smuts declared in 1932 that

the cave "promises to be the most remarkable cave site yet found in

South Africa". Keith Jolly dug here in 1946-1947, and Barbra

Anthony in 1963. Recent work was done by a joint South African and

American team in 2002, investigating what was left of the deposit.

Unfortunately, most of the sediment was removed by the Peers.

Nonetheless, we know that the majority of the

sediment in the cave contained Middle Stone Age tools of types

dated to around 70,000-60,000 years ago. The Middle Stone Age is a

major focus of global research today, as it was during this period

that anatomically modern humans (people like us) first appeared.

The upper portions of the cave have evidence of more recent people,

from within the last 10,000 years. Their tools were different, as

they hunted smaller game, collected shellfish and fish, and

gathered plant food. By 2000 years ago the people living in this

valley were herders of domesticated sheep. There were also some

finds that are likely from the historic period. Jan van Riebeeck

noted in his diary that indigenous people were living in this

valley in the 1650s, and his interpreter 'Harry' spent time here,

perhaps even in this cave.

Even at the time when the 'Fish Hoek Man' was

excavated, there were doubts about its age. The preservation of

this skeleton did not match the other animal bones found in the

same layer. These were very fragmentary compared to the fairly

intact human skeleton. Unfortunately, once something has been dug

up, you can never recreate its position in the layers. Excellent

notes and careful excavation are the only way to dig correctly, as

there is only one chance to get it right. However, bone can be

dated directly using the method of carbon 14 dating. Eventually,

this question was addressed by a group of Cape Town scientists

(Stynder et al, 2009). They dated the skeleton directly, and

determined it to be just over 7000 years old. Even though it is

much younger than previously thought, it is still one of the oldest

skeletons found in the region.

Questions to answer:

- What effect do you think the presence of the large rocks at the

front of the cave had on the archaeological deposits?

- Given the "Law of Superposition", explain why Layer 4 in the

above depiction of the cave's stratigraphy is a problem. (you do

not need to google the cultures mentioned or understand the

archaeology, this is only a question of thinking about the

deposition of these layers logically)

- How do you think the sediment in the cave got here (by what

methods)?

- Where did it come from?

- Look at the sediment in the cave carefully. What colour is it?

What texture does it have? Is this the same as its source? If not,

what do you think caused it to be this colour?

- OPTIONAL: A photo of you and your GPS at the site in your log

is always fun.

References consulted:

Deacon,

J., Wilson, M., 1992. Peers Cave: the "Cave the World Forgot.".

The Digging Stick 9: 2–5. (link)

Heydari,

S., 2007. The impact of geology and geomorphology on cave and

rockshelter archaeological site formation, preservation, and

distribution in the Zagros mountains of Iran. Geoarchaeology

22: 653-669 (link)

Keith,

A., 1931. New discoveries relating to the antiquity of man,

Williams & Norgate LTD, London. (link)

Stynder,

D.D., Brock, F., Sealy, J.C., Wurz, S., Morris, A.G., Volman, T.P.,

2009. A mid-Holocene AMS 14C date for the presumed upper

Pleistocene human skeleton from Peers Cave, South Africa,

Journal of Human Evolution 56, 431-434.

Free counters

|

|

FTF goes to MnCo & Zambesiboy! |

|

|

|