Aviation accidents have been around as long as aviation itself. The first airplane fatality in history occurred in 1908 in Fort Meyer, Virginia when passenger Thomas Selfridge was killed in a plane piloted by none other than Orville Wright (who suffered a broken pelvis, leg and ribs). Unfortunately, aircraft accidents still occur. This cache is a tribute to United Flight 2860, which crashed into Ed's Peak above Kaysville on a snowy night in December 1977, killing all aboard. This cache is located at the crash site.

About the Crash

United 2860 (N8047U) was a McDonnell Douglas DC-8 (the same size as a Boeing 707), a huge aircraft configured to carry 90,000 pounds of cargo instead of the usual 175 passengers. A popular commercial aircraft, it's length was 151 feet, with a 142-foot wingspan and a 43-foot height. It was powered by four wing-mounted jet engines. It could travel at 588 mph with a cruising range of 4,600 miles. In 1961, a test-flown DC-8 became the first civilian jet to break the sound barrier at Mach 1.012 (during a controlled dive) and thereby achieve supersonic flight. This is an actual picture (used by permission of the owner) of United 2860 (N8047U) taken in Seattle, Washington, three months before the plane crashed.

United 2860 (N8047U) was a McDonnell Douglas DC-8 (the same size as a Boeing 707), a huge aircraft configured to carry 90,000 pounds of cargo instead of the usual 175 passengers. A popular commercial aircraft, it's length was 151 feet, with a 142-foot wingspan and a 43-foot height. It was powered by four wing-mounted jet engines. It could travel at 588 mph with a cruising range of 4,600 miles. In 1961, a test-flown DC-8 became the first civilian jet to break the sound barrier at Mach 1.012 (during a controlled dive) and thereby achieve supersonic flight. This is an actual picture (used by permission of the owner) of United 2860 (N8047U) taken in Seattle, Washington, three months before the plane crashed.

A few minutes after midnight on Sunday, December 18, 1977, United 2860 left San Francisco bound for Chicago. Normally the flight was non-stop, but because the cargo that night was only about half of capacity the flight was scheduled to stop in Salt Lake City to pick up a load of Christmas mail. The flight time to Salt Lake was to be 1 hour 12 minutes at a cruising altitude of 37,000 feet. At 1:16 a.m. the flight was nearing Salt Lake City and was cleared to descend to 15,000 feet. The visibility was good at 15 miles. The temperature was 41 degrees, with a light rain falling. The ceiling was 1,700 feet with broken clouds. When the plane arrived in the Salt Lake Valley for an anticipated landing to the south, it was cleared to descend to 6,000 feet, well lower than the mountains on the east. But when the pilot lowered the gear for landing, the instrument lights indicated the landing gear was not locked in place. The pilot radioed to the tower: "Okay, we got . . . a few little problems here, we're trying to check our gear and stuff right now." When the pilot realized it would take some time to resolve the landing gear issue, he requested to be put in a right-turn holding pattern north of the airport. That request was approved, with the plane to remain at 6,000 feet elevation. The pilot confirmed: "Okay, cause we're gonna have to . . . try to find out what the heck is going on."

A minute later, at 1:22 a.m., the pilot asked, "Okay, now can we . . . leave you for a little minute, we wanna call San Francisco a minute?" The controller replied, "United 2860, frequency change approved," to which the pilot responded, "Thank you sir, we'll be back." The plane then switched radio frequencies and contacted United's maintenance control center in San Francisco. One of the plane's four electrical generators had quit working during the flight and after discussion with the maintenance center it was determined that the landing gear lights were powered by the failed generator, thus causing the confusion about whether the landing gear was properly locked in place. The pilot and the maintenance staff concluded it was safe to land.

However, that conversation with the maintenance crew turned out to take not a "little minute," but 7 1/2 minutes, while the maintenance center and the pilot carried on a diagnostic dialog. During that time the air traffic controller in Salt Lake could see from the radar that United 2860, on its eastbound leg of the right-turn holding pattern, was continuing too far east and was getting dangerously close to the Wasatch Mountains. At least three times the controller tried to warn Flight 2860, but the crew was still on a different frequency talking with the maintenance center in San Francisco. At 1:37:26 a.m., Flight 2860 finally returned to the control tower frequency and said "Hello Salt Lake, United 2860 we're back." The tower immediately responded, "United 2860, you're too close to the terrain on the right side for a (right) turn back to the VOR, make a left turn back to the VOR." Probably confused at the directive to break from the right-turn holding pattern, Flight 2860 replied, "Say again," and at 1:37:39 the controller repeated, "You're too close to terrain on the right side for the turn, make a left turn back to the VOR." Flight 2860 responded, "Okay." Ten seconds later, at 1:37:54, the controller asked, "United 2860 do you have light contact with the ground?" Flight 2860 replied, "Negative." A few seconds later at 1:38:00 the controller said, "Okay, climb immediately to maintain 8,000 [feet]." Seven seconds later the controller repeated, "United 2860, climb immediately, maintain 8,000," and four seconds after that, at 1:38:11, Flight 2860 uttered its final words: "United 2860 is out of six for eight." Obviously worried, the controller radioed 25 seconds later, "United 2860, how do you hear?", but there was no response. The plane had already slammed into the mountainside at 1:38:28 a.m. -- a mere one minute after the crew returned to the air traffic control frequency.

Despite the rain, clouds and darkness, several witnesses on the ground in Kaysville and Fruit Heights reported hearing the plane pass low overhead to the east, then seeing a bright orange glow that lasted three or four seconds. The noise of the engines was so loud that it awoke several residents. Merry Green of Fruit Heights said it was like "sitting on the runway" as the plane flew overhead. The aircraft struck the western face of what locals call Ed's Peak, a 7,665 foot high peak between Webb Canyon and Bair Canyon, at about the 7,200 foot level on a magnetic heading of 040 degrees. Ed's Peak is about 1.5 miles due west (downhill) from the northernmost radio tower on the Skyline Drive ridge top, which tower sits about 1.2 miles north of Francis Peak (which hosts, ironically, crucial FAA radar domes) and above the Smith Creek Lakes on the east. The plane virtually disintegrated on impact. The largest intact pieces were the tail section and a piece of one wing. The debris was scattered forward over a 1/4 mile path, 500 feet wide, leaving pieces strewn up the oak brush face of Ed's Peak and down the back side where large pine trees grow. The mountainside was covered at the time with one to four feet of snow.

Despite the rain, clouds and darkness, several witnesses on the ground in Kaysville and Fruit Heights reported hearing the plane pass low overhead to the east, then seeing a bright orange glow that lasted three or four seconds. The noise of the engines was so loud that it awoke several residents. Merry Green of Fruit Heights said it was like "sitting on the runway" as the plane flew overhead. The aircraft struck the western face of what locals call Ed's Peak, a 7,665 foot high peak between Webb Canyon and Bair Canyon, at about the 7,200 foot level on a magnetic heading of 040 degrees. Ed's Peak is about 1.5 miles due west (downhill) from the northernmost radio tower on the Skyline Drive ridge top, which tower sits about 1.2 miles north of Francis Peak (which hosts, ironically, crucial FAA radar domes) and above the Smith Creek Lakes on the east. The plane virtually disintegrated on impact. The largest intact pieces were the tail section and a piece of one wing. The debris was scattered forward over a 1/4 mile path, 500 feet wide, leaving pieces strewn up the oak brush face of Ed's Peak and down the back side where large pine trees grow. The mountainside was covered at the time with one to four feet of snow.

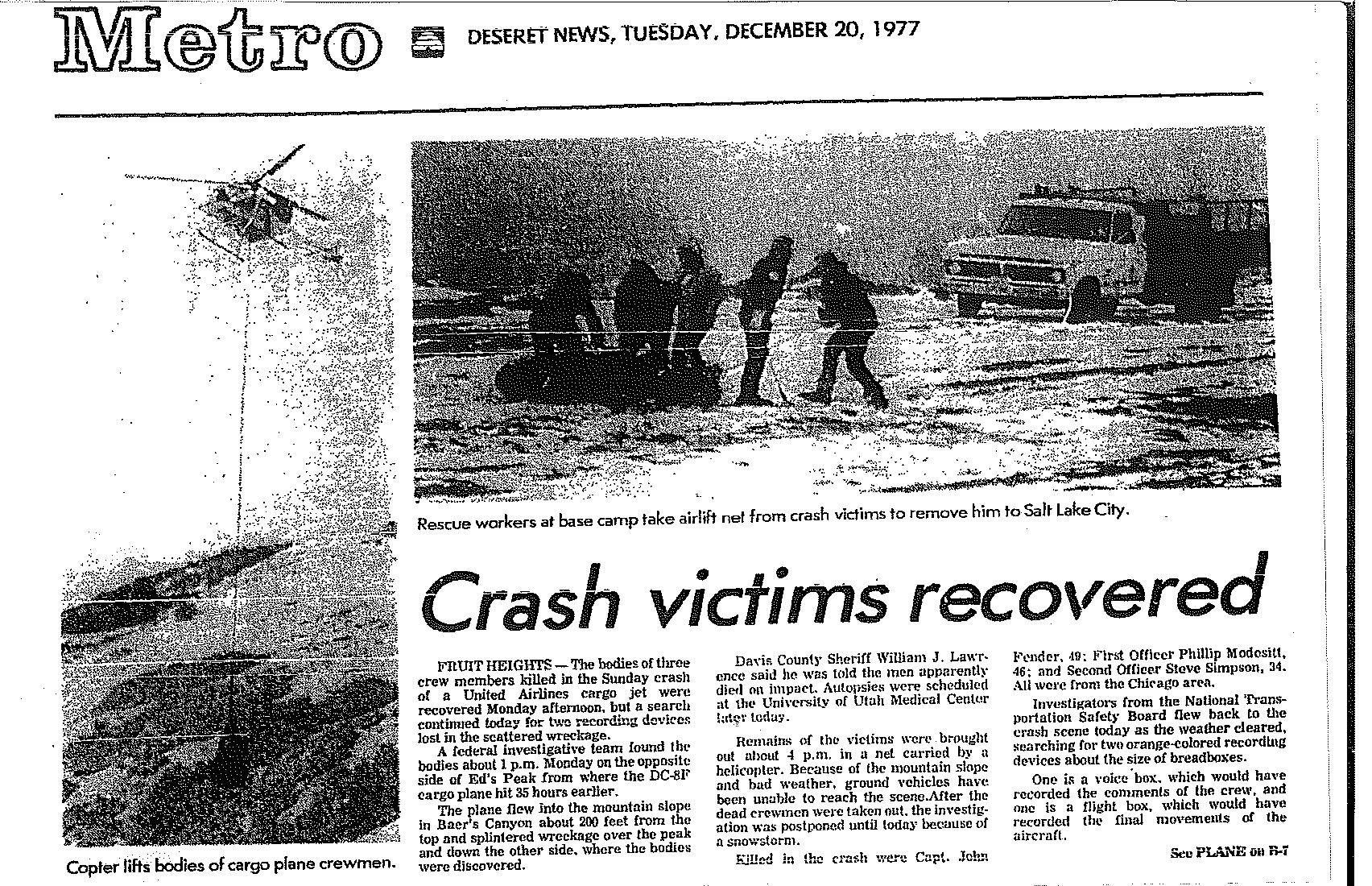

The airport immediately contacted the Davis County Sheriff, William "Dub" Lawrence, who organized a search and rescue mission. More than 100 searchers unsuccessfully combed the area through the darkness and deep snow, finally abandoning the effort until daylight. Because Ed's Peak is about half way up the mountain from Kaysville and half way down the mountain from the top, there are no roads anywhere close to the crash site and the only feasible way for winter access was by helicopter. A helicopter rescue crew from Hill Air Force Base was first to find the crash scene at 10:00 a.m., more than eight hours after the plane went down. A paramedic lowered from the helicopter found widespread debris and conditions indicating that no one could possibly have survived. Because of the extensive debris field, the winter conditions, the steep terrain and the extremely dense vegetation, it took a day and a half of searching by 20 men before the bodies of the three crew members could be found. The bodies were found at the far end of the debris path, on the back side of Ed's Peak in the heavy timber, about 1,200 feet from the place of impact. Aircraft debris reportedly hung from the large pine trees like Christmas decorations.

Killed in the crash were Captain John R. Fender, age 49 (a 23-year veteran with United), First Officer Phillip E. Modesitt, age 46, and Second Officer Steve H. Simpson, age 34. All three were from the Chicago area.

Recovery crews used helicopters to remove the bodies, the cargo and the debris. The flight data recorder ("black box") and cockpit voice recorder were recovered after a few days of searching. Three of the four engines were found and lifted out by helicopter. Most of the fourth engine was never found. Today, 30-plus years later, you can still find debris at the crash site -- mostly very small pieces of aluminum, fiberglass, tubing and plastic (one area with such debris is at N41-02.770, W111-52.431), but scouting around I found a larger piece of the aluminum skin and a large steel engine part that would be awfully heavy for anyone to pack out on foot. The vegetation is very dense in the area and the terrain very rugged, so I'm sure many other obscured pieces still remain, but given the massive size of this airplane and the 43,902 pounds of cargo it carried, it's absolutely amazing that so little debris remains. Someone did a very thorough job of cleaning up the crash debris, and the vegetation is thriving again.

Recovery crews used helicopters to remove the bodies, the cargo and the debris. The flight data recorder ("black box") and cockpit voice recorder were recovered after a few days of searching. Three of the four engines were found and lifted out by helicopter. Most of the fourth engine was never found. Today, 30-plus years later, you can still find debris at the crash site -- mostly very small pieces of aluminum, fiberglass, tubing and plastic (one area with such debris is at N41-02.770, W111-52.431), but scouting around I found a larger piece of the aluminum skin and a large steel engine part that would be awfully heavy for anyone to pack out on foot. The vegetation is very dense in the area and the terrain very rugged, so I'm sure many other obscured pieces still remain, but given the massive size of this airplane and the 43,902 pounds of cargo it carried, it's absolutely amazing that so little debris remains. Someone did a very thorough job of cleaning up the crash debris, and the vegetation is thriving again.

So what caused the accident? The National Transportation Safety Board accident report answers that question, although the investigation was severely handicapped because the critical cockpit voice recorder malfunctioned. (The tape got stuck on a capstan and stopped recording cockpit conversations several days earlier.) Thus, the only information to work with was the flight recorder data, the air traffic control conversations, the United maintenance center conversations, and the accident scene. In short, the plane strayed into fatal terrain because of a failure of communication between air traffic controllers and the pilots; all were at fault. As the NTSB reported, there were "numerous acts of omission and commission, the slight alteration of which probably could have prevented the accident." The first fundamental mistake was failure by the controllers (Murray D. Hess and Boyd R. Beazer) to specify the bearing on which Flight 2860 was to hold. The controllers intended for the plane to be on a holding radial of 330 degrees (the approach vector for a southern landing on runway 16R) which would keep the plane further westward and away from the Wasatch Mountains, while the crew thought (based on instrument settings found at the crash site) the proper radial was 360 degrees (true north). Consequently, when the plane was on its eastbound leg of the rectangular holding pattern, the crew thought it had more allowable time to fly east than it really had. The controllers failed to clearly state what the holding pattern vector should be, and the crew failed to insist on clarification.

In addition, the crew discontinued radio contact with the control tower for too long while checking on the landing gear light problem. Furthermore, the NTSB found that when the crew returned to the tower frequency, the controllers should have been more urgent and forceful in their terrain evasion instructions to the crew. And lastly, the crew should not have hesitated, even for the few seconds it did, after receiving those instructions. Tragically, according to the NTSB, if Flight 2860 had started its left turn only 8 seconds sooner at the time of the initial directive to turn left, or immediately started climbing at that time, it would have missed the mountains. Those 8 seconds of hesitation were deadly. The onboard terrain warning alarm probably activated in the cockpit for the last 8 to 10 seconds, but too late to avoid the mountain rising at a slope of 32 degrees. One can only imagine the horrible feelings the crew experienced during those last 30 or so seconds, knowing they were likely to hit the mountain but unable to see it in the dark and unable to make the plane turn any sharper or climb any faster. As a former pilot, I can think of nothing worse. Indeed, the flight data recorder showed a rapid increase in altitude and a corresponding decrease in airspeed during the last 4 to 5 seconds of flight, indicating that the pilot saw the oncoming mountain in the last seconds and made a futile effort to pull up further.

The NTSB's official probable cause of the accident: The controller's issuance and the flight crew's acceptance of an incomplete and ambiguous holding directive, in combination with the crew's failure to adhere to proper impairment-of-communications procedures and prescribed holding procedures, with a further contributing factor being failure of the aircraft's No. 1 electrical system for unknown reasons.

About the Cache

The cache is located on the southwestern slope of Ed's Peak, about 400 (vertical) feet southwest and downhill from the top of the peak. Most people get there by using the trail that starts near the gun range at Kaysville/Fruit Heights, and there are three other caches on the way along that trail. Look at Nice Place for a Cache (GCG489) for the best starting directions. Next on the trail up is Sunday Morning Stroll (GCP150), and then Peak above Kaysville (GCF076), which is Ed's Peak. The hike up to Ed's Peak is tough, with an elevation gain of about 2,400 feet. The Ed's Peak cache is rated at 4 stars difficulty, so I've rated this one at 4.5 stars because it requires bushwhacking from the trail near Ed's Peak. Alternatively, you can hike down from the top of the Wasatch Mountains, starting at N41-02.990 W111-50.750 where the jeep road ends north of Francis Peak, and heading straight west down the ridge top, through the saddle of aspen trees, then up a ways to Ed's Peak. This route looks reasonable on the topo map and when viewed from the starting point, with an easier elevation difference of 1,800 feet, and this is the route I took in placing the cache given that I was carrying a lot of heavy gear. But I suspect hiking up from the bottom is probably easier overall because there is a decent trail, whereas there isn't anything but occasional game trails coming down from the top, with some really nasty bushwhacking especially through the aspen saddle area (and especially during the summer foliage season). And of course you'll have to hike back up to the top after finding the cache. In any event, TAKE PLENTY OF WATER (you'll need it) and WEAR LONG PANTS AND LONG SLEEVES if you come down from the top, as the oak brush will rip your shins and forearms. (Even with long pants, I wear long-johns to help protect my shins.) And batten down your gear well or the oak brush will grab it for sure. (On previous bushwhacks I've lost maps, water bottles and even a sweatshirt, and on this one I lost my black and yellow Blockade iPod earphones so if anyone sees them let me know!) Perhaps the best strategy is to have someone drop you off from the mountain top, then hike down to the cache, then hike the rest of the way down to the bottom and have someone pick you up. That will save your heart and lungs some work but will surely give your knees an added workout. NOTE that the top-down option won't be possible during much of the year, because the road to Francis Peak is locked shut at the top of Farmington Canyon after the first significant snowfall and doesn't reopen until about June.

The cache contains several newspaper accounts of the crash, as well as three photos of the plane before it crashed (one from Detroit in 1966, one from New York-JFK in 1975, and the one above from Seattle taken just a few months before the crash. PLEASE LEAVE ALL OF THESE MATERIALS IN THE CACHE FOR OTHERS TO SEE.

Be sure to find the nearby Peak above Kaysville cache (GCF076) while you are there.

I erected this memorial at the crash site. The cache is near the memorial. When I placed this cache, on a beautiful fall day with the leaves in brilliant fall colors, there must have been 30 jumbo jets pass overhead, some leaving white vapor trails in the clear blue sky (see photo gallery). And the Francis Peak radar domes sit majestically above the crash site, keeping watch on this hallowed ground and playing their part in airline safety. But this cache is a reminder that while everything usually works out just fine for all of us, life is precious and can end much too soon. I hope you'll take a moment while visiting this cache to pay your respects to the three men who died here.

I erected this memorial at the crash site. The cache is near the memorial. When I placed this cache, on a beautiful fall day with the leaves in brilliant fall colors, there must have been 30 jumbo jets pass overhead, some leaving white vapor trails in the clear blue sky (see photo gallery). And the Francis Peak radar domes sit majestically above the crash site, keeping watch on this hallowed ground and playing their part in airline safety. But this cache is a reminder that while everything usually works out just fine for all of us, life is precious and can end much too soon. I hope you'll take a moment while visiting this cache to pay your respects to the three men who died here.

Winters at the cache site are harsh, so if you find the the memorial in need of any attention please do what you can during your visit to keep it in place and in good shape.

If you find this cache interesting, you might want to check out my other airline crash caches: Memorial to United Flight 4 (GC1JK3C), Memorial to United Flight 16 (GC1JK4M), and Amelia Earhart Crashed Here (GC20R9F).

Be careful and have fun!

Congratulations to peakbagginggeo who was first to find this cache and my other three plane crash caches as well!

Update

On July 9, 2014, I had the honor of hiking to the cache with Aimee-Lynn Simpson Newlan, the daughter of Second Officer Steve Simpson. Aimee traveled here from Chicago to visit the site of her father's death 37 years ago just before Christmas when Aimee was only 9 years old. With the strong support of Aimee's husband Brad, Mike Snow from the Davis County Search and Rescue Team, former Davis County Sheriff Dub Lawrence, and others, Aimee made the difficult hike to this cache, hoping to find peace and closure and to pay tribute to her father. It was not easy for her, but she did it! We're all proud of you, Aimee!! You can see the story of Aimee's journey here.

I added to the cache some letters, photos, news clippings and other personal papers that Steve Simpson's widow (Aimee's mother) asked to be placed in the cache. They are heartbreaking to me, to see such a vibrant, happy young family separated by this tragedy, but heartwarming to me to see the support given to the Simpson family by local residents and town leaders following the accident. These documents are sacred. Please, of course, read them, but treat them with the respect they deserve and leave them in the cache for others to see.

To the Simpson family (Sharon, Aimee-Lynn, Brad and Steve), we love you, and we hope this memorial will continue to bring peace and respect to your family. Thanks for letting us join you on this special adventure.

Dan

Dub

Dave

Mike

Doug

Cory

Ben

Scott

Logan