From the cache position, you have a

lovely

view of the domes of the South African Astronomical Observatory

(SAAO). Quite a photogenic spot actually, especially with these

special rocks in the foreground which are often

snow-covered

in winter. Be warned – it can get very windy here which can

make it impossible to do the bonus question (see Question 5 below)!

The site is open to the public during the day for

visits,

the ideal opportunity to do this cache (as well as the

other one here.) [I work

for SAAO, based in Cape Town, but often come to work in Sutherland.

I would love to meet you, so feel free to contact me when you come

and do this cache to see if I’ll be here.]

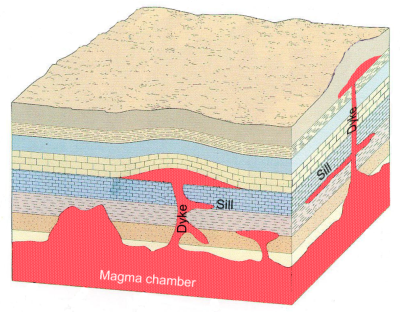

We pick up the geological story well after the sedimentary rock

layers of the Karoo Basin formed, but before the break-up of the

super continent, Pangea (meaning Entire Earth). [If you want

to know how this happened, visit my

Cutting edge

(GC1XGM6) EarthCache, about 100 km south of here.] All the

strata were still horizontal and in tact then, with the surface

probably about 2000m above where you are standing now.

About 130 million years ago this grand continent began to split

up into Gondwana (the southern part) and Laurasia,

then into various smaller pieces, triggering volcanic activity.

Because of this movement, and due to the enormous pressure of the

molten rock (magma) from below, vertical cracks formed, creating

pathways for the magma to push up into from deep within the Earth.

Quite often the rising magma was unable to reach the surface and

produce volcanoes, but the pressure was so great that the molten

rock was able to lift the higher layers of rock (which was

horizontally stratified and therefore was weakest along horizontal

planes) and squirted horizontally into the gaps made, forming

sheets between the sedimentary layers, sometimes hundreds of

kilometers in extent (see sketch below). These “sills” cooled

quickly through contact with the local rock, solidifying into very

small crystals (unlike, e.g. the deep igneous intrusion of Paarl

Rock, which cooled very slowly and formed large crystals). The

result is a fine-grain granite known as “dolerite” (Greek:

doleros, meaning "deceptive"). The vertical feeder channels

also coagulated in what are known as “dykes”. The sills and dykes

are thus younger than the sandstone and mudstone deposits.

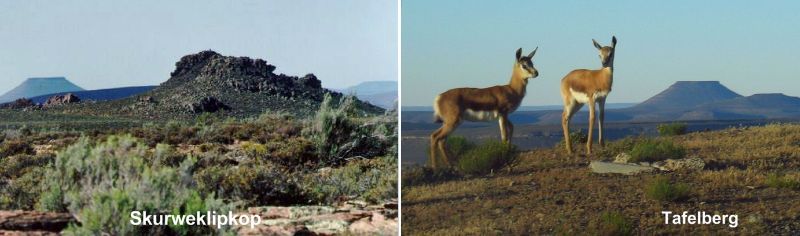

Over the millennia the sedimentary layers eroded away to the

level we see today. However, the very hard dolerite resist

weathering, producing flat top “mesas” (flat tableland with steep

edges), a familiar sight throughout the Karoo. Because the harder

rocks weather more slowly, these hills are in effect held up from

their tops, and only wear down as the softer rocks below undermine

the harder layers. The plateau that you, and the SAAO telescopes

are on, is in fact such a dolerite sill. And if you look NNE, just

past SALT (bearing 19°, 24 km away), you will see a very distinct

flat-topped hill, called Tafelberg (Table Mountain), which is also

a remaining piece of a sill.

There is also a good example of a dyke conveniently nearby –

look NNW (bearing 330°, distance 4.2 km). This rocky outcrop is

officially named Skuweklipkop (directly translated; “Rough Stone

Hill”) although our local astronomers have an equally appropriate

nickname for it (see Question 3 below). This feeder channel would

have created a sill far above it, now entirely eroded away.

You may wonder why I brought you here since these features are

better visible from elsewhere on site, as can be seen in the above

pictures (something to look out for when you drive out). It is

because the surprise I mentioned, is right here! If you are at GZ

(ground zero) – and weather permitting – you are probably sitting

on it! You are amongst a heap of washing-machine-sized boulders.

Now find a fist-sized stone and start tapping these boulders (try

the other boulders too). What do you hear? If you could quickly

learn to play the

lithophone,

we must arrange a rock concert!

But wait ... there’s more! Normally EarthCaches do not involve

any hidden treasures, but for your tapping convenience, I left a

hammer amongst the rocks at GZ. Please hide it again afterwards and

shout if it breaks (you will see that it is home-made).

To appreciate how unique these rocks are, verify for yourself

that

Wikipedia

only lists five such sites worldwide. It is interesting that most

of these sites claim that scientists are still unable to explain

the physical mechanism that cause the rocks to sound like this.

However, my source, Prof Brian Warner, explained: “When the

intrusion of molten rock occurred, the liquid rock cooled so

quickly that the crystals didn’t have time to grow large, with the

result that the dolerite is (a) almost microcrystalline and (b)

almost uniform in constitution. This resembles a metallic

structure. The rocks can vibrate coherently because there are no

internal inhomogenieties to damp the sound waves.” It is

interesting to note that in Afrikaans, dolerite is also referred to

as “Ysterklip” (Iron Rock). It makes one wonder if it was perhaps

the acoustic properties of dolerite that lead to this name.

(Source:

Prof Brian

Warner

Department of Astronomy, University of Cape Town , South Africa

AND

School of Physics and Astronomy, University of Southampton,

UK.)

To claim “Found it” you must email me satisfactory responses to

the following:

Any logs not accompanied by an email will be deleted.

- Send me a picture of you/your party with your navigation device

taken at this spot.

- Search for an example piece of dolerite that broke off,

revealing its internal structure and colour. If you compare this

structure and colour with your average granite kitchen tabletop,

name one similarity and one difference between the two.

- Where do you think the local astronomers’ nickname of “Camel

Rock” for Skurweklipkop originated.

- Say for argument sake that magma was never forced in between

the stratifications at this site, meaning the local geology just

composed of regular sedimentary mudstone and sandstone layering. Do

you think the Observatory could still have been build here? Explain

your answer?

- For a bonus, first download

this video clip

and tell me if you recognise the tune [hint: it fits in with the

purpose of this site]. Then see if you can improve on my attempt by

sending me a sound/video recording of your rock music composition.

[How about a Metallica piece!]

Note: Do not post any spoiler

pictures/hints to this page, even if encrypted.