Maritime forest and beach dune environments are fragile ecosystems. Do not, under any circumstances, leave the established trails to climb around on any of the dunes, and do not disturb any of the nesting shorebirds that you may encounter on your visit. Sandy Hook supports many nesting pairs of Piping Plovers, which are an endangered species, so please respect their privacy. Remember, you are visiting their home.

Evolution of Sandy Hook

Sandy Hook is a club-shaped, 9-mile sand spit that extends north from the New Jersey mainland into New York Harbor, dividing the open ocean of the New York Bight Apex to the east from the shallow, protected Sandy Hook Bay and Raritan Bay to the west. It is the only undeveloped barrier beach area on the northern end of the New Jersey coastline north of Island Beach State Park, located 34 miles to the south. Sandy Hook has formed where currents from the Atlantic Ocean and Lower Raritan Bay meet to promote deposition of granular materials. This results in localized shallowing, or shoaling, of the water. However, these shoals are not stationary and continually shift with the action of the waves and ocean currents, so the shape of size of Sandy Hook is constantly changing, with the sandy beach at the northern end tip continuing to accrete new material to lengthen the peninsula.

Sandy Hook is a club-shaped, 9-mile sand spit that extends north from the New Jersey mainland into New York Harbor, dividing the open ocean of the New York Bight Apex to the east from the shallow, protected Sandy Hook Bay and Raritan Bay to the west. It is the only undeveloped barrier beach area on the northern end of the New Jersey coastline north of Island Beach State Park, located 34 miles to the south. Sandy Hook has formed where currents from the Atlantic Ocean and Lower Raritan Bay meet to promote deposition of granular materials. This results in localized shallowing, or shoaling, of the water. However, these shoals are not stationary and continually shift with the action of the waves and ocean currents, so the shape of size of Sandy Hook is constantly changing, with the sandy beach at the northern end tip continuing to accrete new material to lengthen the peninsula.

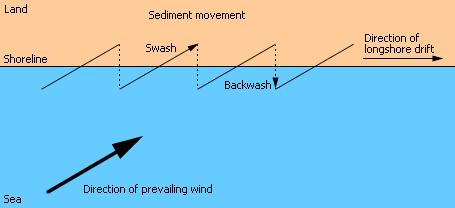

Longshore drift, sometimes known as littoral drift is the geological process by which sand and other materials are moved along the shore line by wave action. As an incoming wave breaks, water washes up onto shore, causing sand and other light particles to be transported up the beach. This action is known as swash. The direction of the swash varies with the prevailing wind, so the waves typically approach the coastline at an angle, pushing material up the beach at the same angle. After reaching its maximum reach up the beach, the water recedes back into the ocean, dragging material down the line of the steepest gradient along the beach, perpendicular (90° angle) to the shoreline at that point. This produces a zig-zag movement of sediment along the beach, and has the overall effect of straightening the shoreline over long periods of time.

Longshore drift, sometimes known as littoral drift is the geological process by which sand and other materials are moved along the shore line by wave action. As an incoming wave breaks, water washes up onto shore, causing sand and other light particles to be transported up the beach. This action is known as swash. The direction of the swash varies with the prevailing wind, so the waves typically approach the coastline at an angle, pushing material up the beach at the same angle. After reaching its maximum reach up the beach, the water recedes back into the ocean, dragging material down the line of the steepest gradient along the beach, perpendicular (90° angle) to the shoreline at that point. This produces a zig-zag movement of sediment along the beach, and has the overall effect of straightening the shoreline over long periods of time.

As sand accumulates on the beach, prevailing onshore winds blow it inland where it becomes trapped by obstacles such as vegetation and pebbles. As the sand grains get trapped they begin to accumulate and start of formation of dunes. The winds then begins to erode the growing mound of sand by moving particles from the windward side and depositing them on the leeward side. Gradually this action causes the dune to “migrate” inland, accumulating more and more sand in the process. The conditions on a young dune are harsh, constantly bombarded with salt spray from the sea carried on strong winds. The dune is well drained and often dry. Rotting material washed onto the shore adds nutrients to allow pioneer grass species to colonize the dune. The deep roots of these plants bind the sand together, and the dune grows into a fore-dune (ocean side) as more sand is blown over the grasses. The grasses add nitrogen to the soil, meaning other, less hardy plants can then start to colonize the dunes. These species are adapted to the low soil water content and add humus to the soil as the plants die and decay. As the dunes grow, they provide privacy and shelter from the wind and salt, so that more species of plants can start to flourish. Over time, evergreen maritime forests develop in the back-dune (bay side) area and provide wooded habitat for mammals and birds.

As sand accumulates on the beach, prevailing onshore winds blow it inland where it becomes trapped by obstacles such as vegetation and pebbles. As the sand grains get trapped they begin to accumulate and start of formation of dunes. The winds then begins to erode the growing mound of sand by moving particles from the windward side and depositing them on the leeward side. Gradually this action causes the dune to “migrate” inland, accumulating more and more sand in the process. The conditions on a young dune are harsh, constantly bombarded with salt spray from the sea carried on strong winds. The dune is well drained and often dry. Rotting material washed onto the shore adds nutrients to allow pioneer grass species to colonize the dune. The deep roots of these plants bind the sand together, and the dune grows into a fore-dune (ocean side) as more sand is blown over the grasses. The grasses add nitrogen to the soil, meaning other, less hardy plants can then start to colonize the dunes. These species are adapted to the low soil water content and add humus to the soil as the plants die and decay. As the dunes grow, they provide privacy and shelter from the wind and salt, so that more species of plants can start to flourish. Over time, evergreen maritime forests develop in the back-dune (bay side) area and provide wooded habitat for mammals and birds.

The Maritime Forest

Sandy Hook has one of the few maritime forests still present along the northern New Jersey shore. Sandy Hook is rich in ecological diversity, featuring seven miles of ocean beaches and sand dunes, salt and freshwater marshes, and 264 acres of maritime forest. The fore-dunes are populated with American beachgrass (Ammophila breviligulata). Extensive areas of back-dune habitat occur toward the northern end, with dry sandy soils supporting shrubby vegetation dominated by winged sumac (Rhus copallina), bayberry, beach plum, and tree-of-heaven. Two distinct maritime forest areas occur in Sandy Hook, including a 225 acre mixed-deciduous forest with dense vegetation dominated by

Sandy Hook has one of the few maritime forests still present along the northern New Jersey shore. Sandy Hook is rich in ecological diversity, featuring seven miles of ocean beaches and sand dunes, salt and freshwater marshes, and 264 acres of maritime forest. The fore-dunes are populated with American beachgrass (Ammophila breviligulata). Extensive areas of back-dune habitat occur toward the northern end, with dry sandy soils supporting shrubby vegetation dominated by winged sumac (Rhus copallina), bayberry, beach plum, and tree-of-heaven. Two distinct maritime forest areas occur in Sandy Hook, including a 225 acre mixed-deciduous forest with dense vegetation dominated by  American holly (Ilex opaca), black cherry, hackberry, serviceberry (Amelanchier canadensis), greenbrier (Smilax rotundifolia), and poison ivy (Toxidendron radicans). A second, smaller 60-acre forest occurs on the bay side of the peninsula with greater dominance by holly and presence of Eastern Redcedar (Juniperus virginiana). The backside of the spit consists of extensive tidal mud and sandflats and salt marsh dominated by low marsh cordgrass inhabited by a variety of invertebrates. There are also a few small inland marsh areas dominated by common reed.

American holly (Ilex opaca), black cherry, hackberry, serviceberry (Amelanchier canadensis), greenbrier (Smilax rotundifolia), and poison ivy (Toxidendron radicans). A second, smaller 60-acre forest occurs on the bay side of the peninsula with greater dominance by holly and presence of Eastern Redcedar (Juniperus virginiana). The backside of the spit consists of extensive tidal mud and sandflats and salt marsh dominated by low marsh cordgrass inhabited by a variety of invertebrates. There are also a few small inland marsh areas dominated by common reed.

Maritime forests that occur at Sandy Hook occur at only a few other locations in the region and are a globally imperiled community due to their rarity. The forests are important as roosting and nesting locations for a variety of birds, and include historical nesting by great blue heron, historical nesting and present roosting by black-crowned night-heron (Nycticorax nycticorax), and nesting by several pairs of osprey and several species of passerines. There has been a steady increase in the number of nesting pairs of endangered piping plovers at Sandy Hook, with the productivity of the Sandy Hook plovers consistently being the highest in New Jersey.

Maritime forests that occur at Sandy Hook occur at only a few other locations in the region and are a globally imperiled community due to their rarity. The forests are important as roosting and nesting locations for a variety of birds, and include historical nesting by great blue heron, historical nesting and present roosting by black-crowned night-heron (Nycticorax nycticorax), and nesting by several pairs of osprey and several species of passerines. There has been a steady increase in the number of nesting pairs of endangered piping plovers at Sandy Hook, with the productivity of the Sandy Hook plovers consistently being the highest in New Jersey.

To receive credit for this Earthcache, there are four activities that must be completed:

1) Beginning at the posted coordinates, take a stroll along the Old Dune Trail. If you wish, a guide for the numbered signs along the trail may be obtained at the nearby Sandy Hook Visitor Center. Observe the different types of plants that are present in this martime forest section of Sandy Hook. Post pictures of your GPS with three different types of plants that you encounter.

At 40° 25.861'N, 73° 59.092'W you will encounter a small information sign describing how the dunes provide necessary protection from the elements and allow the development of maritime forests. Be sure to stop to read the information on this sign as you will need it to answer the next question.

2) After reading the information sign, turn right and proceed to 40° 25.875'N, 73° 59.014'W. At this location, the trail crosses through a dune and out onto the open beach. As you pass between the dunes, notice the distinct difference in vegetation between the foredune and backdune environments. Using the information on the trail sign and information presented on this cache page, send an email explaining this phenomenon. Pictures of this area are highly encouraged, but not required.

3) Continue out onto the beach. Observe the shape and general appearance of the shoreline at this location. In the same email, describe evidence of the littoral drift process that you observe.

4) Return to the trail and walk perpendicular to the shoreline through the maritime forest to the point where the trail intersects the Sandy Hook Bike Path at 40° 25.817'N, 73° 59.191'W. In the same email, briefly describe how the size and variety of vegetation changes as you move farther from the ocean and how this change is indicative of a typical maritime forest progression.

At this point, you have completed the requirements of the Sandy Hook Maritime Forest Earthcache. You can return to your car via the bike path, or continue to explore more of the trails and enjoy what Sandy Hook has to offer.