Big Rock Earthcache EarthCache

-

Difficulty:

-

-

Terrain:

-

Size:  (other)

(other)

Please note Use of geocaching.com services is subject to the terms and conditions

in our disclaimer.

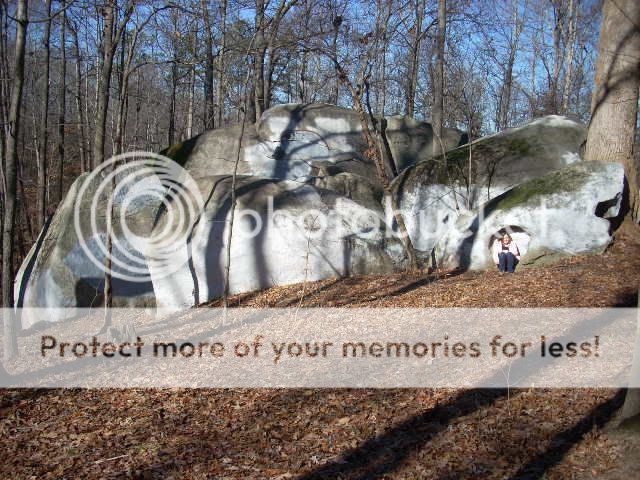

Big Rock. Photo by foxult.

Big Rock. Photo by foxult.

Big Rock (also known locally as “Indian Rock”) is located in a small, Mecklenburg County park called Big Rock Park in the Thornhill subdivision. Park on the street and hike a few hundred feet to the rocks, which will be clearly visible on a well-worn trail. There are no bathrooms or water. Parts of the outcrop are steep with sheer cliffs, so watch your step and keep a close eye on your kids, but the good news is that you won’t have to climb on the rocks.

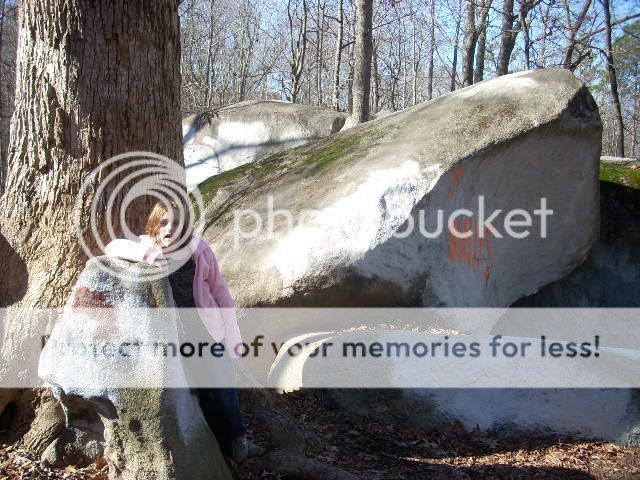

Closer shot of Big Rock. Photo by foxult.

Closer shot of Big Rock. Photo by foxult.

From the Thornhill Community website:

“The Big Rock was a campsite, rendezvous point, and observation post for the first human beings who inhabited what is now Mecklenburg County: ancient Native Americans, whose forbearers had migrated from Asia, some 40,000 years ago. These initial nomads reached the Carolina Piedmont about 12,000 years ago. They had wandered over the Blue Ridge and Smoky Mountains in pursuit of big game. Living in highly mobile and lightly equipped groups, the Indians ambushed their prey, principally now extinct giant mammals, by thrusting spears into their flanks at close range.

“There is a small crevice or indentation on the backside of the eastern wall of the Big Rock. It would have provided protection from the strong, cold winds that blew across the almost treeless grasslands that covered the surrounding countryside in ancient times. Imagine what it must have been like for the small bands of Indians who spent wintry nights at the Big Rock thousands of years ago. The howl of wolves would have echoed in the pitch-black darkness. The Indians would have chipped stones into spear points, and roasted hunks of fatty meat in the flickering flames of the campfire. Arising at first light, these small assemblages of nomadic hunters would have resumed their ceaseless chase after the herds of mammoth, horses, camels and bison that meandered across the Piedmont landscape.”

This granitic outcrop rises from the wooded hillside as a result of millennia of weathering and erosion. Although “weathering” and “erosion” are often used erroneously as synonyms, weathering is the breakdown of a rock while erosion is the process of transporting weathered rock fragments by water, gravity, wind, or glaciers (there’s no evidence of glacial activity in Charlotte).

Weathering: Freeze and Thaw

One way to weather a rock is through freezing and thawing. When water from rain or snowmelt soaks into a rock and the temperature drops below 32 degrees Fahrenheit, the water expands as it changes from a liquid to a solid. This expansion breaks up the surrounding rock and the pieces fall to the ground (by gravity) where they can be transported by water or wind. Look around the base of Big Rock for tiny rock pieces fallen from the rock face.

Weathering: Root Wedging

Root wedging in Bell Rock, Sedona, AZ. Photo by foxult.

When plant roots work their way into cracks in the rock, they pry apart the rock in a weathering process called root wedging. Although all plant roots can root wedge, tree roots make the most dramatic photos. Search the rocks for dramatic root action.

Tree trying to grow around the Rock. Photo by foxult.

Differential Erosion

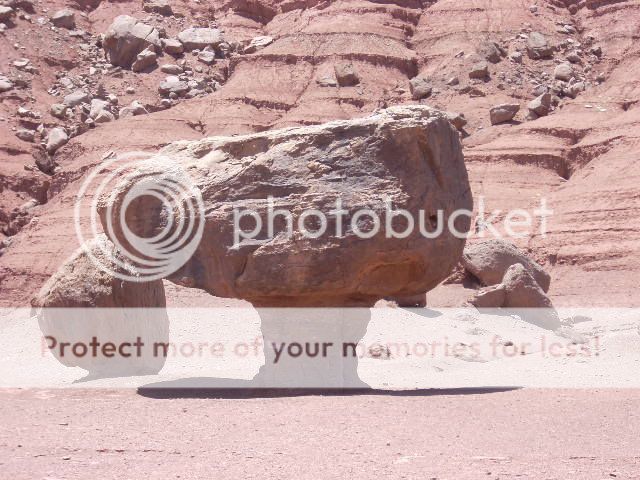

Hoodoo near Lee’s Ferry, AZ, where the rock of the base is eroding faster than the rock on the top. Photo by foxult.

Hoodoo near Lee’s Ferry, AZ, where the rock of the base is eroding faster than the rock on the top. Photo by foxult.

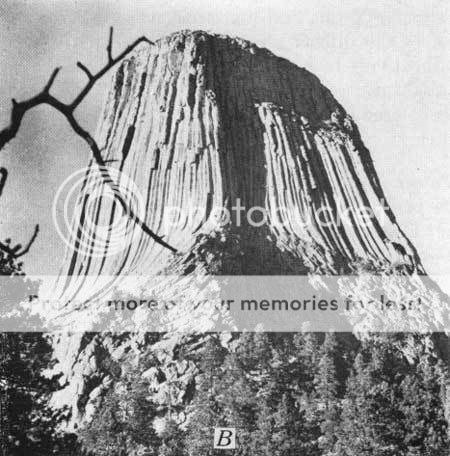

Differential erosion occurs when rocks erode at varying speeds. It happens all over the world in all climates. Anytime you see photos of a mountain peak or isolated rock outcrop such as Devil’s Tower in WY (see photo) or Stone Mountain in GA, you’re looking at a product of differential erosion. The granitic rocks of Big Rock erode more slowly than the rocks and soil that surround it, which is why you can see Big Rock sticking out of the hillside.

Devil’s Tower, WY.

Differential erosion can occur on a rock’s surface, too. Individual minerals weather and erode at varying speeds. Look carefully at the surface of Big Rock and note how some minerals protrude more than others—that’s differential erosion on a small scale.

Differential erosion on Big Rock’s surface. Photo by foxult.

Differential erosion on Big Rock’s surface. Photo by foxult.

To log this EarthCache, do the following.

1) Take a picture of yourself and your GPS with Big Rock in the background.

2) Take a picture of root wedging you see at Big Rock.

3) Go to the West (tallest, steepest) side of the outcrop, and you’ll see an overhang. Explain how the overhang formed.

4) Do either of the following:

a) Measure the area of the exposed rock in acres, square feet, or square meters. To make this calculation easier, think of Big Rock as a circle.

Area of a circle = (pi) r^2.

Circumference of a circle = 2 (pi) r.

Use 3.14 as the value of pi.

r = radius of the circle.

Explain your method of measuring. i.e. – How did you get your answer?

b) OR measure the volume of the exposed rock. To make this calculation easier, you can treat the exposed rock as a half of a sphere, which means you can use the formula for the volume of a sphere and divide by two.

Volume of a sphere = 4/3 (pi) r^3

r = radius of the exposed rock.

Use 3.14 for the value of pi.

The units of volume should be cubic feet or cubic meters.

Explain how you got your measurements/answer.

5) Extra credit task: Identify one mineral in the rock.

For further reading about the geology of the Carolinas, read

Carolina Rocks!: The Geology of South Carolina by Carolyn Hanna Murphy.

Exploring the Geology of the Carolinas: A Field Guide to Favorite Places from Chimney Rock to Charleston by Kevin G. Stewart and Mary-Russell Roberson.

Sources

Thornhill Community website:

http://thornhillnc.net/Default.aspx?tabid=96

Devil’s Tower photo:

http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/deto/images/fig53b.jpg

Additional Hints

(No hints available.)